A little reflecting on art history can help make the problem of the opposition of conceptual and visual art abundantly clear. As all students of art history know, Marcel Duchamp kicked off the conceptual art ball rolling when he tried to exhibit a urinal as a sculpture in an art exhibit put on by “The Society of Independent Artists” in 1917. Anyone who paid a small fee could exhibit in the show, and so Duchamp got the clever idea of submitting a urinal, and calling it, “The Fountain”. Witty, witty. Not surprisingly, the board of the society ultimately rejected it. Duchamp, who was a member of the board himself, resigned in protest. So the story goes*.

A little reflecting on art history can help make the problem of the opposition of conceptual and visual art abundantly clear. As all students of art history know, Marcel Duchamp kicked off the conceptual art ball rolling when he tried to exhibit a urinal as a sculpture in an art exhibit put on by “The Society of Independent Artists” in 1917. Anyone who paid a small fee could exhibit in the show, and so Duchamp got the clever idea of submitting a urinal, and calling it, “The Fountain”. Witty, witty. Not surprisingly, the board of the society ultimately rejected it. Duchamp, who was a member of the board himself, resigned in protest. So the story goes*.

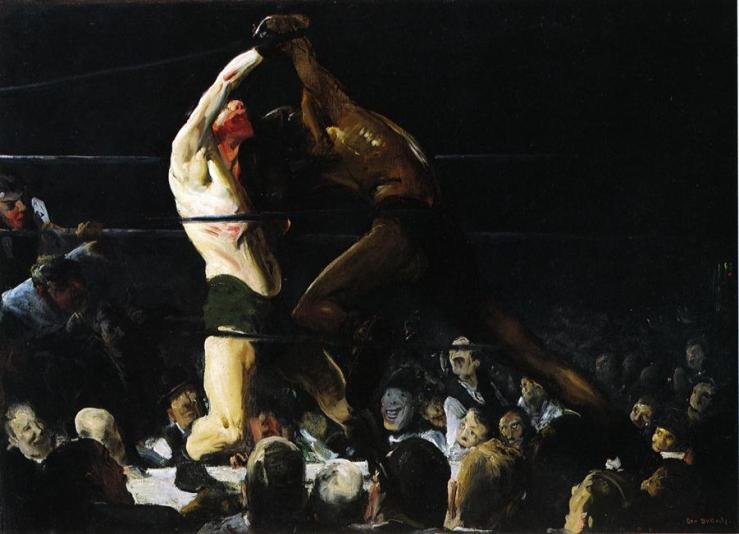

With hindsight it is generally accepted that the board, including painters such as George Bellows, were shortsighted. Those of us who have been through art education take this so for granted that we miss the obvious. Duchamp didn’t submit what would one day be appreciated as among the greatest artistic achievements of the century. He submitted the most vile insult to the other artists, and their art, that he could possibly get away with. The only thing worse than a urinal would have been a pile of dog shit on a newspaper.

Nowadays we don’t find it odd to see Duchamp’s “Fountain” displayed in a museum alongside paintings, but it’s worth investigating why it really IS odd.

Duchamp tried to include a piece that was a rejection of visual art into an exhibit of visual art. Today we accept that those who refused to honor his denigration of their own art, and the underlying premise of their exhibition and careers, were being snobs and old fogeys. We miss that it was much more snobbish to toss a urinal in an art exhibit and declare it better than anything any of the artists had spent months working on. Should they really have seen the light, and marveled at the piss pot? Should they have accepted that their own art was implicitly irrelevant, and something to be urinated on? Probably they shouldn’t have, in the same way that the dinosaurs shouldn’t have allowed rodents to eat their eggs, and hasten their own extinction. Or at least that’s how we see it now.

From the vantage of the present, Duchamp’s statement was extraordinary. He freed the imagination from the tyranny of painting! He showed us that anything can be art, and anyone can be an artist. He opened the door to every kind of art making, and all possibilities. This was not only a great artistic achievement, it was a momentous awakening for the human species.

Or not. Imagine the same principles as applied to music. In order to free the mind from the dictatorship of music having to follow structure – notes, melody, harmony, polyphony, rhythm, and all that – a revolutionary musician flushed a toilet during a musical recital (Yes, I know John Cage did things similar to this). This flushing of the toilet is not only regarded as equal to the symphonies of Gustav Mahler, Dimitri Shostakovich, Igor Stravinsky, and Morton Subotnick, it is recognized as superior. And not only is it better than their work, it’s better than any of the conventional music, such as rock and jazz, that came afterward. Anything can be music, anyone can be a musician, and anything that is not musical language is superior to it.

This creative free-for-all is all fine and good, but “The Fountain” was not a monumental achievement in visual art or philosophy, and it doesn’t replace visual art or prove it moribund. Anyone can be creative, and anything can be a creation, but anti-art isn’t really visual art, and anti-music isn’t really music. It’s ANOTHER art form entirely. This can still be confusing because a urinal can be seen (but doesn’t merit looking at), so it seems possible to categorize it as visual art.

In order to cut through all the decades of rhetoric that obfuscates the obvious, please indulge me in another analogy. Let’s say I think fiction is washed up. I don’t want to deal with grammar, character development, plot, suspense, or denouement… I decide to rebel against novel writing, and as a gesture I submit a phone directory in a competition for The Great American Novel. The catch is I signed my name on the cover, and in so doing declared it “literature”. I sit in an easy chair and puff at a cigarette congratulating myself for nailing the lid on the coffin of the novel, and ushering in a new era in which any text can and must be evaluated on a par with classical literature.

I boldly declare that my gesture of submitting the phone book proves irrevocably that the novel is dead, and my contribution implicitly dwarfs the literary achievements of George Eliot, James Joyce, William Faulkner, Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, and Arundhati Roy… This is the same exact thing as Duchamp submitting a urinal as a sculpture. But my phone directory still seems ridiculous. You will have objections to it as a novel, but the same objections apply to “The Fountain”. Let’s break this down with a table.

The important criticism is that my “novel” wasn’t intended to be read, and can’t really be read. Everyone can understand that a list of names, even though it has countless words, does not form a coherent story. But people seem to forget that there is a difference between something deliberately composed using the “visual language” of balancing colors, arranging shapes, modeling forms, creating movement, using lighting and perspective…, and something that merely can be seen because it isn’t invisible.

The important criticism is that my “novel” wasn’t intended to be read, and can’t really be read. Everyone can understand that a list of names, even though it has countless words, does not form a coherent story. But people seem to forget that there is a difference between something deliberately composed using the “visual language” of balancing colors, arranging shapes, modeling forms, creating movement, using lighting and perspective…, and something that merely can be seen because it isn’t invisible.

Visual art is expressly created to be looked at. Duchamp’s pioneer urinal, on the other hand, was by his own admission, chosen because it was innocuous and its form was not worthy of contemplation.

“My idea was to choose an object that wouldn’t attract me by its beauty or its ugliness. To find a point of indifference in my looking at it.” ~ Marcel Duchamp.

He repeated this in different ways, so I think we can assume it’s really what he meant to say. Here are a couple more from an interview which you can listen to on YouTube.

“The fact of choosing, selecting, and deciding on one was the result of being very careful about not using my sense of beauty or my belief in some aesthetics… in other words, finding some object of complete indifference, as far as aesthetics are concerned.” ~ Marcel Duchamp.

“The difficulty is to make people understand that it was not through an attraction of beauty of the object that I would call it a readymade. That’s why I made so few, because after a certain while anything becomes beautiful. You know, it takes 40 years sometimes, for my, what’s it called, the “Bottle Rack” to become very [indecipherable]. People say it’s so beautiful, and that’s the worst complement they can give me.” ~ Marcel Duchamp.

If Duchamp wasn’t trying to get us to see the unalloyed beauty of the utilitarian object, what was his great contribution? This is where explanations get so arcane that they are virtually incomprehensible. Consider this explication from art critic, Jerry Saltz:

“The readymades provide a way around inflexible either-or aesthetic propositions. They represent a Copernican shift in art. Fountain is what’s called an “acheropoietoi,” an image not shaped by the hands of an artist. Fountain brings us into contact with an original that is still an original but that also exists in an altered philosophical and metaphysical state. It is a manifestation of the Kantian sublime: A work of art that transcends a form but that is also intelligible, an object that strikes down an idea while allowing it to spring up stronger.” ~ Jerry Saltz

If you need to couch your argument in an avalanche of jargon, use vocabulary that nobody knows or can pronounce, and site a philosopher that died in 1804, it’s a sure sign that what you are saying is so obvious and trite that if you said it directly, people’s response would be, “So what?” Basically, this obtuse paragraph says, “Duchamp called utilitarian objects ‘art’. Wow!”. Talk about making a mountain out of a molehill.

Whether or not one believes in that sort of explanation, or is just so impressed by it that they assume whoever wrote it must know more than they do, or be smarter, and therefore must be right, the point remains that the urinal is not visual art, because it does not use visual language. It is calculated to frustrate attempts to read it visually, which is why it’s called “anti-art”.

“Fountain was many things, apart, obviously, from a mis-described piece of sanitary equipment. It was unexpectedly a rather beautiful object in its own right and a blindingly brilliant logical move, check-mating all conventional ideas about art. But it was also a highly successful practical joke.

Duchamp has been compared to Leonardo da Vinci, as a profound philosopher-artist…” ~ Martin Gayford, for The Telegraph.

It’s quite a claim to say any artist is on a caliber with da Vinci, and this is how many view Duchamp. On what grounds should we accept that he is so great? The article only offers the same banal idea that Jerry Shaltz argued, which originated with a text accompanying a photo of the urinal in an avant-garde magazine published in 1918:

“Whether Mr Mutt [Duchamp] made the fountain with his own hands or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object.”

The counter to this argument I find much easier to understand, and much harder to dismantle:

“Whoopty fuckin’ do.”

Much importance is placed on how Duchamp rocked the worlds of the conservative artists, like Bellows, who were shocked and appalled at his revolutionary and subversive gesture of submitting a urinal to an exhibit. Little mention, on the other hand, is made to his also insisting that they exhibit all the art alphabetically, with the first letter being drawn out of a hat: an idea they accepted. Nor is it advertised that the urinal was only narrowly voted not to be included. Claiming Duchamp shocked the board of the exhibit, who went along with his other trivializing suggestion and almost included his urinal, is like claiming Al Gore suffered a crushing defeat in the 2000 election, when he lost by a mere 537 (probably padded) votes. If he’d shocked them any less they’d have put his urinal on a pedestal in the center of the exhibit, served wine out of it, and made it a conversation piece.

There is also another, less fawning interpretation of Duchamp’s legacy, which is that he was bitter about the rejection of his Nude Descending a Staircase from the Parisian Salon des Indépendants in 1912, and, even though it was accepted by other groups, decided to write off painting.

…I went immediately to the show and took my painting home in a taxi. It was really a turning point in my life, I can assure you. I saw that I would not be very much interested in groups after that. ~ Marcel Duchamp.

Duchamp may have felt he couldn’t compete with other painters, such as Picasso, and he had a difficult time coming up with ideas and finishing works.

“I didn’t have any ideas to express. I didn’t, never, considered myself like a professional painter. You know, a professional painter is a man who paints every morning. And he paints quickly or slowly, but he paints all the time. And painting always bored me. Imagine. So, I had a hard time finishing a painting.” ~ Marcel Duchamp

Having difficulty with painting, Duchamp sought to find some other way to trump painters, and submitted the urinal to the “The Society of Independent Artists” of 1917, out of spite.

He was considered a minor and negligible artist for the first half of the century, and was only resurrected after American art ascended to primacy in the art world – with the extensive help of the CIA in a covert Cold War effort to promote American culture – and Duchamp was retroactively embraced, in a revisionist version of art history, as seminally important because of his influence on American artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol. When the American government’s role in distorting art history for political ends – placing itself at the center of the art world – was finally uncovered, it was too late to undo all the isms and radical developments that were spawned in accordance with a skewed art history that awarded some artists far too much significance for ulterior purposes, while sidelining other possibly better art to obscurity or ignominy. Perhaps Duchamp’s true place in art history lies somewhere between being a convenient pawn in an American attempt to claim cultural world supremacy, and being the demigod of avant-garde art.

I find it’s often very useful to see what artists have to say for themselves, what they were about, and why. If we are going to accord an artist the philosophical might of da Vinci, we might also give his own words some weight.

Duchamp’s position was surprisingly easy to understand, even if it was more than a tad dull and belabored. Duchamp didn’t like what he saw as the “retinal” in art, which is art that was supposedly designed to appeal to the eye and not the intellect. He found all the artists after Gustave Courbet to be lacking in story telling, and detested the Impressionists the most. Never mind that this may reflect his own conservativism about painting, and an inability to fathom what the Impressionists were really about [note that his dismissal of the merely retinal would also include Van Gogh].

Disgusted with visual beauty, Duchamp sought something completely devoid of aesthetics, be it beauty or ugliness. He chose the innocuous. And for some of us his taste in the completely uninteresting was unswervingly accurate, so good in fact that the objects he selected remain stultifyingly boring to this day.

The goal of his readymades was absolute indifference:

“There’s no style there, and no taste, and no liking, and no disliking either”.~ Marcel Duchamp.

We may be tempted to try to find beauty in the mundane, but to do so is to completely miss the point of the philosophical giant. Painting bored him, beauty was anathema, and he wanted to get rid of art altogether.

“I don’t care about the word ‘art’ because it’s been so discredited, and so forth… I really want to get rid of it, in the way many people today have done away with religion. It’s sort of an unnecessary adoration of art, today, which I find unnecessary. And I think, I don’t know, this is a difficult position, because I’ve been in it all the time, and still want to get rid of it, you see.” ~ Marcel Duchamp.

When discussing the “happenings” of artists such as Allan Kaprow, the most appealing aspect of them was, for Duchamp, the aim of boredom:

When discussing the “happenings” of artists such as Allan Kaprow, the most appealing aspect of them was, for Duchamp, the aim of boredom:

The point they brought out so well, and an interesting one, is they play for you a play of boredom. It has been… I’m not discovering that, but, it’s very interesting to have used boredom as an aim to attract the public, when the public comes not to be amused, but to be bored. ~ Duchamp.

Duchamp is surely one of the most boring artists of the 20th century, and that is a title he would be proud of. He sought the bland which could only be interesting at all in direct proportion to just how uninteresting it was, and he did this in the name of eradicating the beautiful in art, and ridding the world of art altogether. For some that’s thin-ass, flavorless gruel, while for others it’s a grand philosophical/artistic statement that puts him on a par with da Vinci.

Let’s take a look at one more of his most lauded pieces, the magnificent L.H.O.O.Q., and then I’ll wrap this bad puppy up. In this ground-breaking, even Earth-shattering masterpiece, the modern day da Vinci upstaged the original by adding a beard, mustache, and bawdy title to a print of the Mona Lisa.

For what it’s worth, I can remember when I first saw this piece. It was presented in one of my art classes at UCLA in a survey of the most important art of the 20th century.

My reaction was not even a guffaw. By the time I saw this, drawing a mustache on any picture was the first thing anyone would do, unthinkingly, to mock it. I’d drawn multiple mustaches on photos in magazines in elementary school myself. I don’t know whether L.H.O.O.Q. was the first time someone drew a mustache on a woman’s face, but I really doubt it. It was, however, probably the first time someone had the audacity to do so and then exhibit the result as a worthwhile work of art in itself. Upon being exposed to this as a young art student, my response was to struggle to stay awake. It seemed dusty, trivial, and a mere footnote to art history: something hastily scribbled in the margins. The whole slide show was dreary, because none of slides the teacher selected were intrinsically visually interesting. I wanted to be moved, inspired, awed, and for life to be rich and exciting. Instead I got a dusty, cynical, dry joke.

The reason we should appreciate L.H.O.O.Q. is because it is an attack on the Mona Lisa and traditional art values. That’s it folks. Very well, then, Duchamp has attacked the tradition of aesthetics, visual language, and beauty. For me there are not one, but two fatal flaws with this tactic.

- If the art Duchamp attacks is merely retinal, and thus insignificant, a mere comment on the inherently worthless can only be so powerful. Duchamp’s work in question has no intrinsic value as visual art, and only has significance in relation to other works that it presumes to gain import by piggy-backing off of.

- Duchamp attacks the tradition of visual art, but stops there. He offers no alternative. For most of his career he stopped making art, and instead devoted himself to Chess. Meanwhile other artists continued to innovate richly interesting visual art.

And this reminds me of a story, so I will digress a little further. When I was studying art in college, my sculpture teacher was rumored to have spit in front of a student’s work, and said, “My spit is more interesting than that”. Supposedly, the student had made a totem pole, and the teacher, being an avant-gardist, sought to illustrate a profound philosophical point by showing that traditionalism was so utterly worthless that an action of spitting, here, in the now, in reality, trumped it. This is the Duchampian gambit, positioning yourself as better than something by denouncing it, not unlike a child congratulating himself for kicking down someone else’s sandcastle.

However, I do love a good prank, so, in the tradition of Duchamp, I offer you the following.

When Duchamp threw the urinal in an art exhibit, he also threw in the towel. He gave up on painting, on aesthetics, and on visual language in general, and he did this before Surrealism or Abstract Expressionism. He had no idea where to take painting, but with hindsight we now know unequivocally there was still room for innovation and discovery then, and I believe there still is today. His gestures weren’t a continuation of the tradition of visual art, nor an evolution of it, but rather something else entirely (if we are going to grant them more than being props for stunts that are mere commentary on art and footnotes to art history).

Art is what the institution of art says it is, and this is no more apparent than in the praise of an anti-artist as among the very best artists of the 20th century, even if he largely gave up on art and played Chess instead. We consider walking away from art a momentous artistic achievement when it is attributed to an art celebrity. We even consider making oneself a celebrity, as Warhol did, art. This is an entirely extrinsic appreciation of art, in which the context the art is put in decides its merit. Art loses its intrinsic power, and becomes an artifact in a master narrative of art history, valued for it’s alleged importance in a domino effect of isms.

The degree to which the art narrative is skewed, serves ulterior purposes, or is a mere fabrication upon reality, is the degree to which the value of art is rendered arbitrary. Anything no matter how bad can be great, and anything no matter how good can be completely disregarded as insignificant. The ideas surrounding art have replaced art at the center of the discourse, and art itself is largely irrelevant except as an investment, or a marker in someone’s fiction of history. This view of art history is like prizing novels for their various claims to innovation or political import, collecting them, admiring their covers, learning about the authors, and analyzing the history of literature, without every bothering to read them.

The visual has been replaced by the word in visual art to the degree that the word said the visual was dead, we believed it, and we crowned the word the height of visual language. Consider that Duchamp argued that his work didn’t necessarily need to be seen. The idea was more important than the object, which was intended to hold no visual interest whatsoever, in which case you only need know about the provocation and the ideas it spawned. Now imagine music that is not intended to be listened to, and doesn’t even need to be heard, is considered the best of the best music of the 20th century. The ideas about art have replaced art, and the people with the ideas have replaced artists. Everything is backwards. Art should not be subordinate to this or that arbitrary context, and should instead be appreciated the way we appreciate music, for its intrinsic worth and the pleasure we experience in partaking of it.

In Duchamp’s “The Fountain” or “L.H.O.O.Q.” we can see the root of the problem of why so many people hate conceptual art. Not only does it want to destroy visual art, which has always been based on aesthetics, but it wants to claim to be on a par with the all-time best art and artists. For those who love visual art, and want to savor an image, conceptual art offers little to nothing (in the same way my conceptual novel offers nothing worthwhile to read), and yet claims to be better than visual art. Duchamp’s work has nothing to do with da Vinci, and the scant record of his philosophizing is difficult to distinguish from Solipsistic posturing.

Personally speaking, I have always prefered to be enraptured rather than bored shitless, and find I have to supply all the energy in order to find interest in the flatly innocuous. But there’s no accounting for tastes, as my favorite art critic’s love of Phillip Guston proves. Many prefer the kind of art that is the uncooked, unflavored Tofu of the art world.

Whatever your preferences, art which is opposed to aesthetics and visual language should not be put in the same category as visual art, and definitely should not be respected as the best example of it (in the same way fasting can’t really count as one’s best meal). Conceptual art can, however, exist as a separate form of creativity, which is recognized as having as little or as much to do with visual art as it has to do with music or literature, but which has an enormous range of its own exciting and interesting possibilities (assuming it can leave the cult of the boring behind, Jeff Koons “Banality” series not excepted).

*There’s some recent scholarship casting doubt on the veracity of this, and if this is true it would give more power to my arguments, but I don’t mind wrangling with the full force of the official story.

Why People Hate Conceptual Art: Part 1

Why People Hate Conceptual Art: Part 2

Why People Hate Conceptual Art: Part 3

Stay tuned for parts 5, 6, and 7.

~ Ends

Does this explain Peter Liks b & w photograph ‘Phantom’ selling for 6.5 million dollars. Arizona’s Antelope Canyon, a natural cavern carved out of multicolored sandstone by flowing water is a much photographed spot, but due to the beautiful coloration rarely shot in black and white.

Peter has managed to make it more boring and hence more valuable “Art.”

LikeLike

Another great post in the series. And as I was reading I was thinking it must be incredibly frustrating to be part of a discipline that has lost its way in the greater, bigger scheme of things. But then, education has well and it seems to be the way of the world these days. I don’t know if we will see the re-birth of art and education and humanity on earth, but I certainly hope so.

LikeLike

My two – actually 2015 – cents (as someone with hardly any position in the local art world, but with an interest in modern arts and literature -since an early age- that has only increased. Spoiler: Most of the texts – or “poems”, if you may call them as such – I have written are indebted to Dada and Surrealism… and what I currently write is just a tad more “poetic” than that Manhattan Yellow Pages displayed as novel – if you want, google “conceptual writing” -, so I’m biased. Snobbish? Quite probably, but I find it normal to be excited by such things. Forgive my digression:)

– “Duchamp attacks the tradition of visual art, but stops there. He offers no alternative.” You may complain about this, but keep in the mind that the entire Dadaist movement was nihilistic in this exact way. He didn’t want to establish a new tradition, just like the Dadaists from Zürıch did not set out to come with a new “system”, as they were against “systems”. Of course, the success of that nihilism was limited: Paris Dada morphed into Surrealism (which had a system). And so the ready-made was picked up by the Dadaist offshoots of the post-war period. Abstract Expressionist painter Robert Motherwell was instrumental to New York (re)discovering Dada, then it was a matter of time before they would be absorbed by the new academic stream. It’s true: the neo/post avant-garde brought about a new academicism. Conceptual art is the crowning achievement (in terms of radicalism, of course) of this modern academicism, hence why it is and it will remain powerful until the end of the academic art world (at least as we know it).

– “Meanwhile other artists continued to innovate richly interesting visual art.” Well, his kins, like Suzanne Duchamp and Jacques Villon, are underrated artists, but I understand why someone would consider Marcel Duchamp’s path more interesting. He has authored few works in over five decades – and it’s exactly this sterility that intrigues me (at the very least). Quite a lot of modern artists and writers were obsessed with sterility and self-erasure. There was a Surrealist poet from my country who only published one poem during his entire lifetime. I’ve read somewhere that the Japanese artists from the Mono-ha movement (with ephemeral land art and installations of natural and artificial elements – a sort of minimalism using traditionally Japanese aesthetic ideas) stopped creating objects altogether in the 1970’s until not many years ago. Maybe others wouldn’t call them (visual) artists or whatever, but I find these matters very fascinating. Just my opinion though, I guess.

– “He had no idea where to take painting, but with hindsight we now know unequivocally there was still room for innovation and discovery then, and I believe there still is today.” I’m not sure about today, we can be certain about 1915, but the point is that he wasn’t interested in creating “art” anymore. The ready-made was his attempt of saying that he doesn’t believe in art anymore. Problem is… “art” wasn’t actually a substantial attribute of the so-called “art object” in the first place, but rather a judgment, as at least Thierry de Duve claims. He says that, after “Fountain”, one can only accept the ready-made in the territory of art or reject it – and there’s no way out of this dilemma. I’d add that it doesn’t even matter outside a philosophical debate and that we all work in the real world with “hashtags”. But we love debates, right?

– Am I wrong if I claim that you are more or less subscribing to what Tom Wolfe has written in The Painted Word? I wouldn’t mind if “conceptual creativity” would be a category of its own (there are forms of conceptualism attached to literature, music etc. too), the kinds of creativity involved are certainly different. But I’m fully aware that I have the liberty to say this long after a historical struggle in which conceptual artists thrived in the art world, while others did not. At least now we can decide to no longer see things in terms of conflict, although that’s what it obviously was. My complaint would be that painters such as yourself seem a bit too much preoccupied of taking the “revenge”. What I can see here from your paintings or from those of the Stuckists does not interest me – if we were to talk about even modern in general art, I doubt the value of these recycling-Expressionism approach. But, like I said, I’m biased, I’m in a different framework (in which having skill or not is completely irrelevant compared to the outcome).

LikeLike

A lot of this may be a matter of tastes, and conformity (in your case) to academia. For example, if you don’t much appreciate visual art to begin with, than your preference for what you call “nihilist” and “sterile” productions is meaningless. You may say you vastly prefer English to Chinese, but if you don’t speak Chinese, then that says nothing. So, if you don’t love the tradition of painting, than your disavowal of it in favor of Duchamp’s unrelated games and conceptual tidbits is completely irrelevant. In the same way, if someone tells me that rap music is vastly superior, and more relevant than, say, the music of Stravinski, I can’t take them seriously if they have no understanding of Stravinski.

I think I’ve already dismantled your brand of rhetoric in multiple articles so there’s not much for me to do but repeat myself in response. Anyway I’m happy to debate you if you like.

You quote me as saying that Duchamp didn’t want to start a new tradition. I didn’t say “tradition”, I said “anything else”, which would be some sort of alternative work. I have no interest in “traditions” or movements, which is all part of the faux linear progression of art history. I’m just talking about alternative works in the same genre, not some other genre.

Duchamp is the equivalent of someone declaring contemporary classical music washed up and then offering a door buzzer as an alternative. It’s not in the same arena of creation. Art that is intentionally anti-aesthetic and gives us nothing to look at can’t replace art that is intended to be looked at, in the same way poison is a rich rhetorical alternative to food, but can’t supplant it.

You seem to find it fascinating when an artist or writer does nothing, whereas I find it crushingly boring, the equivalent of following the career of the prize fighter who never gets in the ring.

When I said that other “artists continued to innovate richly interesting visual art” while Duchamp took an extended break to play Chess, I wasn’t talking about Suzanne Duchamp and Jaques Villon. We can go a little broader than Duchamp’s own circle. How about Picasso, Max Ernst, and the Surrealists and Abstract Expressionists in general? I find them more interesting than Duchuamp’s dusty celebration of the mind-numbing, and stultifyingly mundane.

Of course you are allowed to be fascinated and excited by conceptual “nihilism” and “sterility” in academia. I find it crushingly, tediously boring and trivial – mere mental masturbation. You may be much more interested in ideas about art than art itself, and may be attracted to the possibility (even though it’s complete bullshit) of shaking up the whole world, or art world, with the wave of a desultory hand.

You wrote, “the point is that he wasn’t interested in creating “art” anymore”. And thus he is not interesting as an artist, if you are interested in art. However, if you are interested in “sterile” ideas and “sterility” in general, that’s another realm. Personally I have no more interest in that than I do in ballroom dance or curling.

You wrote, “after “Fountain”, one can only accept the ready-made in the territory of art or reject it – and there’s no way out of this dilemma.” Sure there is. You can accept it as very loosely art (in the way that music and literature are art) but not as “visual art”, and more specifically understand it as a prank and commentary on art. Either/or black and white divisions are for the simple-minded reductionist.

“Am I wrong if I claim that you are more or less subscribing to what Tom Wolfe has written in The Painted Word?” Most likely you are wrong. Can you paraphrase whatever Tom Wolfe’s position is?

You wrote, “My complaint would be that painters such as yourself seem a bit too much preoccupied of taking the “revenge”. If you read more of my criticism, or looked closely at my work, you’d know that I work digitally, and that my stated position is that the reason there is animosity between conceptual art and visual art is that conceptual artists position themselves as evolving out of visual art and rendering it irrelevant. In reality conceptual art is simply another, and unrelated genre, and if people could appreciate that the antagonism would disappear.

This shouldn’t be hard for you to understand. Some people love visual art, and an alternative to visual art needs to satisfy the same thing. We want something interesting to look at, and offering us something that is deliberately uninteresting isn’t going to do the trick. When I want to listen to music, anti-music, such as the sound of a buzzer, isn’t going to satisfy me. So, art that tries to make an interesting image is entirely different from music, literature, or conceptual art. They are wholly different categories. If you don’t like visual art, that’s fine, but Duchamp has little more to do with visual art than with music, or Rugby. Today’s conceptual art is its own field. It should not be lumped together with image-making.

“What I can see here from your paintings or from those of the Stuckists does not interest me”. The Stuckists? Your arguments and those of the Stuckists don’t interest me either. You didn’t even notice that my art is digital. You might also be interested to know that I’ve had serious debates with the leader of the Stuckist movement, and am not a part of it, largely because I believe in innovation, professionalism, and using new media and technology. I forget the guy’s name at the moment, but he basically argued that my art is only “conceptually art” because it is digital. Never mind for the moment I can make a one off print on metal and hit him over the head with it. You have no idea what my art is or is about, mostly because you haven’t given it the time of day, and have no apparent interest or appreciation of the tradition of visual art. If you don’t like visual art – which is the art of making imagery – than your opinion is as meaningless as your lack of interest in literature written in a language you can’t read.

“I doubt the value of these recycling-Expressionism approach”. To the degree my work is “Expressionistic” I’ll take that as a compliment, because I have no problem with conveying feeling in art and trying to address the human condition (it’s rather a timeless pursuit so “recycling” is wrong, trying to make a fundamental kind of art into a style in the aforementioned “faux linear progression of art”) but my art has an element of humor, ironic remove, use of (lack of) materials, and subject matter that are very different. You may be interested to know that not only do the Stuckists dislike and reject my work, so do traditional painters in general. Why might that be?

“But, like I said, I’m biased, I’m in a different framework (in which having skill or not is completely irrelevant compared to the outcome).” Yes, you are biased. And what you are interested strikes me as mental masturbation. If I want Philosophy, I’ll go straight to the source. Why don’t you read my article on the question of “skill” in art. https://artofericwayne.com/2015/01/13/the-debate-over-skill-in-visual-art-and-conceptual-art/

You are underestimating me, my thought on art, and my art, assuming that just because I love visual images that I am lagging behind. No, that’s not it. I am like a musician who admits to himself that I got into music because I loved Rock, and I’m going to try to make songs that I find meaningful, even though the high fashion is to say that the song is over, and conceptual non-music is the new music.

How can I make this more clear? If you want to say Kung Fu is washed up, you need to have a better fighting style. If you aren’t interested in Martial Arts at all, than it’s irrelevant to say if one or another style doesn’t interest you. Duchamp didn’t make a better painting or image. He did something else.

By me, all this dusty conceptualism, which I learned decades ago (my graduate thesis was an installation), is old and boring. I think making complex imagery on the computer is much more interesting, and one doesn’t have to be a millionaire or well-connected to do it. The real challenge is to the individual’s imagination. If you don’t like my visual art, just make more interesting images yourself, and I will become your fan. But, if you are against visual art, again, you are just an English speaker poo-pooing Chinese. The challenge of visual art is to make a new and compelling image. That is not best achieved by not even attempting anything like it, but doing something else altogether. Your preference for conceptual productions is as pertinent as preferring fishing to poetry.

On the other hand, I do like that Duchamp punked the art world, and I punk the art world, too. I’ve done it quite a lot, but here’s a post that puts several of them in one place. https://artofericwayne.com/2014/01/09/worst-than-hirst-a-review-of-my-work/

In reality I like conceptual art, and can do it myself, but I like image making a lot more, and reject the easy, arrogant assumption that conceptual art in any way replaces visual art.

LikeLike

I think the great artistry here is convincing people it’s worthy art. The artist has to put much thought and effort into spin-doctoring a point and contriving just the right moody artist image to convince the art world elite that his work has merit and is better than the rest.

These artists inspire me. Every time I come across effortless ‘art’ in a gallery I realize there is greatness in me yet!

But, then I go home and put time, thought and passion into a painting and fail as an artist.

LikeLike

Sad and funny and true. I think you have to actually be a painter these days to be able to really understand that conceptual art has nothing to do with image-making, and is a separate kind of art altogether. For example, it makes so much more sense to compare Ducham’s urinal “fountain” to sculpture rather than painting, because it is much more in that tradition. Conceptual art in general has as much to do with painting as it does with music, and yet conceptual art and painting are lumped together, and conceptual art is believed to have replaced painting in a linear history of visual art.

LikeLike

Both this article and your reply to yigruzeltil in the comment above really encapsulates in a well-articulated way my thoughts on the whole ordeal. Mainly the lumping-together of concept and visual arts as the same thing. Being inserted into the world of digital illustration, I regularly come across the same old tired arguments against contemporary art. These arguments come essentially from being uninformed on the subject. Much like how you were talking about conceptual artists deeming visual arts inferior by wrongfully setting it as the next step in a linear historical sequence instead of a separate thing altogether, these illustrators are also under the same impression, and as such feel cheated for some reason. In fact, you don’t need to be in this circle. the average person with no art instruction will share facebook posts about how a blue painting sold for millions, but a pretty concept design for a video-game isn’t celebrated. It all comes down to ignorance of the subject being critiqued. Like the conceptualist critiquing painting for being passé doesn’t dabble in it enough to apreciate its virtues, the typical illustrator or designer equally bashes “contemporary art” by lumping it all together in a category and by not understanding how the criteria they’re used to in evaluating their kind of art shouldn’t apply to it. Apples and oranges. The lack of understanding in the subject sometimes is so bad that some people will lump conceptual art together with anything done post-renaissance as the same “pretentious shit”. If only everyone could understand how these are all different things. Your analogies do a really good job in illustrating this point.

(Also, sorry if this post is a mess. Not only is english not my native language, I’m not that good with words either. Hence my delight in finding someone who can make these points so well)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Ivo:

Yes, generally people fall into one camp or another, artistically, politically, and otherwise. It seems the art world is a little slow to accept digital art as “fine art”, though David Hockney has exhibited lots of paintings that were created in an Ipad, and Richard Prince gets away with just printing out other people’s Instragram posts.Hockney should, however, be a safe meeting ground for the type of artists you linked to, and also the more traditional physical/paint oriented folk, who often dismiss my digital art automatically ans somehow unreal.

I’ve been experimenting with digital painting for about a decade, and mostly used only Photoshop, rather religiously, but have recently expanded my repertoire to include the programs you mentioned, as well as dipping into 3D with Blender and now Zbrush.

For my process I make each stroke individually (more than once over), and don’t brush/stamps or painting filters. If one works digitally, with some experience, there are multiple possible approaches to achieving plausibly similar effects.

Thanks for sharing the artwork, as I hadn’t see those before.

LikeLike

Great read!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for helping a novice understand this. Time well spent. God bless you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

where is part 5 & 6?

LikeLike

I never got around to them, because, when I originally posted this article, nobody have a crap, and I was just writing to myself.

LikeLike