Van Gogh is the stuff of legend, perhaps more for slicing a chunk off his ear, or shooting himself in the stomach in a field, than for his paintings. He died an abysmal failure, enduring condemnation and humiliation. When he lived in Arles, for example, eighty people signed a petition stating he was dangerous and urging he be removed from the community. That would hardly reaffirm ones sense of social worth.

What interests me about all of this now is why people couldn’t see anything of value in his art while he was alive, and why his work is universally admired now. And of course, as one of tens of thousands of artists who don’t make squat off of their work, I can relate.

The familiar simple answer is just that people didn’t get his paintings; his work was ahead of its time; and they weren’t ready for it. That may be roughly accurate. But I also wonder if his work was really so much ahead of its time, as opposed to outside of time. Not just a chapter or two in the lead, but beyond consensual reality. The viewer has to make a mental leap to grasp the work, and I’m not confident people even nowadays, despite Van Gogh being so popular that he’s a whopping cliché, actually can and do make that leap. We may be even less able to fathom his work than were his contemporaries.

If one looks, Van Gogh has many living detractors. Here are some savory appraisals from the blogosphere:

my summary judgment is that van gogh is a trainwreck marketed as a tragedy, and ineptitude marketed as innovation.

somewhere between the lonely suicide who couldn’t sell his paintings and the bloated myth romanticized by irving stone and fleshed out in film by kirk douglas, the art marketing juggernaut of the van gogh myth was born. and it’s been rolling over gullible, conforming eyes ever since.

Right, you might be thinking I pride myself on getting Van Gogh, and I’m a pompous ass. Not really. I don’t get them all. I do have an advantage in having had a few good art history classes, read several books on Van Gogh, and went through the crucible of attaining a Masters in fine art. It helps to be an artist with a painting background. But in the same way I wouldn’t presume to fully comprehend Miles Davis [or insert name of great Jazz musician of choice] I know my scope isn’t going to encompass someone elses, and I’m not going to fully understand everything they say, and every way they express it. Note that I’m not really a fan of jazz, so it’s easy for me to admit that I haven’t invested the time necessary to get into it. And you are entitled to not like Van Gogh. I, for one, don’t really care for Matisse.

Understanding Van Gogh’s paintings is not just about accepting the formal aspects of his technique as a viable approach, and then understanding why that is significant in a theoretical history of art. This is probably the most popular way of understanding art today – analyzing the theoretical underpinnings and being able to maneuver the ideas like chess pieces – but you could achieve that abstract understanding without ever looking at the work.

And it’s not seeing his paintings as psychological artifacts of madness. That is to force and project an interpretation on them and not to see them for what they offer. Such an approach sees his paintings as symptoms of mental illness. Look, this is how a lunatic sees the world!

His canvases succeed in spite of his battles with mental illness, not because of them. Painting was how he anchored himself, gave himself hope, purpose, and structure. If anything they are documents of relative sanity in the face of lack of affirmation from society or his crumbling life.

Then there is the angle that he’s a “genius” and his art is a sort of alchemy. This fetishizes his work with a seemingly incontrovertible celebrity and authority. This view appreciates it in the same way one might a lock of hair from Marilyn Monroe: all of its worth is due to association, and is not intrinsic. And I don’t think Van Gogh thought of himself as a genius, as that seems a more modern conception. His approach was staggering humility and hard work.

Post Modernism and deconstructionism hold that the meaning of a text, or image, is determined by the reader or viewer and not by the creator. That is an elaborately woven rhetorical piece of bullshit. One only need to think of times we’ve gotten song lyrics wrong to invalidate this stance. In Ozzy Osborne’s “Crazy Train” he sings, “mental wounds not healing”, but I heard, “pencil bone not healing”, which didn’t make any sense to me and annoyed me. Was my interpretation the true one, and Ozzy’s secondary? To really appreciate a work of art, we need to meet the artist on his or her own terms, and not just superimpose our own ideology and rhetoric on it. Freudian and feminist readings of literature are often guilty of just this.

So to get Van Gogh means to make a mental leap to see the world as he chose to depict it. It’s a bit like learning a language, in this case his use of visual language. Despite the seeming simplicity of his pure colors and bold outlines, he is not an easy artist to grasp. When I first discovered him as a teen I wasn’t drawn to things like his glorification of workman’s boots (I was more drawn to Dali’s imaginary landscapes), though I did notice and admire his bold use of colored outlines. I would have understood his drawing first, because his use of color is more sophisticated.

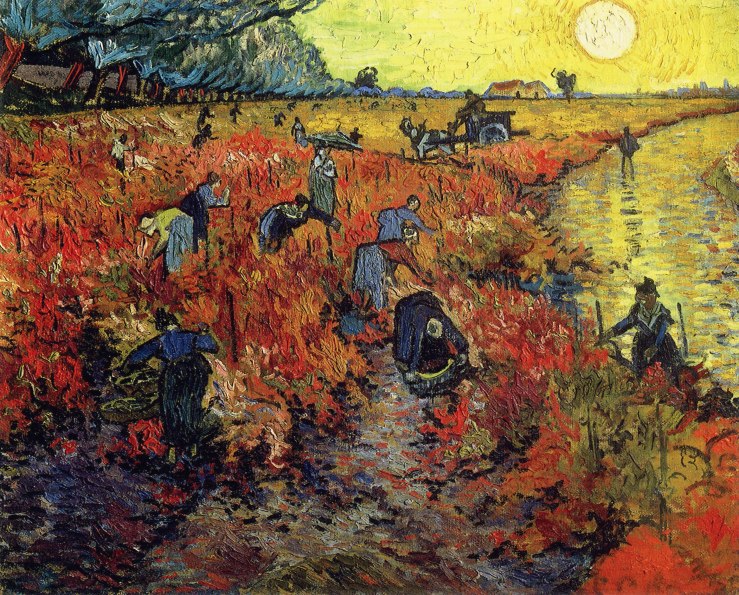

Van Gogh is an artist I come back to and see with new eyes. It takes maturity, sincerity, and humility to meet him on his own ground, and we may get closer without ever fully arriving. But I think we can all notice the river is shimmering gold, the vineyard is a vegetable fire, the sky is yellow blending to green, and the trees are blue. That’s enough to sink ones teeth into. We don’t necessarily need to apperceive how his work integrates and harnesses his beliefs with his process, craft, and imagery.

I’m guessing in Van Gogh’s time people found his work crude and amateurish, not realizing he’d sacrificed realism and intricate draftsmanship for a compromise with radiant color, thick paint, and conspicuously directional brush strokes. And I’m also guessing people later came to admire him because authority said he was a master, and they’d seen reproductions of images like Starry Night hundreds of times, in which case sheer saturation of exposure creates an iconic quality. Once his work was promoted, people could at least give it a chance and let it sink in a bit, instead of scoffing at it, and so they stopped resisting it and came to enjoy it on some level.

But if his work had not been promoted, would people today really value it at all? Or would they pass it up for images of boobs, unicorns, wolves and whole moons? I sometimes think that art is a bit like math, and the more sophisticated it is, the less people truly understand it. It may be that people value the legend and the priceless artifacts, but don’t care about the artist’s work much beyond getting it in as a backdrop of a selfie.

Do people still value being contemplative before a still image? Or do they just click “like”, because it reaffirms something they think they believe in, and move on? Painting may not have died, but our eyes for seeing it could have atrophied.

Do people still value being contemplative before a still image? Or do they just click “like”, because it reaffirms something they think they believe in, and move on? Painting may not have died, but our eyes for seeing it could have atrophied.

As art critic John Seed laments with sarcasm:

If you have an “eye for art” and a keen interest in inspecting the surface of works of art, both out of curiosity and a quest for deeper meaning, your abilities are linked to an increasingly outdated notion of connoisseurship. Having an “ear” for art — which means that you pay attention to what people are saying about what is hot on the market — is the best tool for keeping up with the trends.”

The only painting sold in Van Gogh’s life was an exceptionally great one, bought by a fellow painter, Impressionist Anna Boch. I don’t doubt she understood the beauty and audacity of Red Vineyard. Most his contemporaries, on the other hand, wouldn’t make the mental leap, and if it weren’t for the crutch of celebrity and authority, we may be flattering ourselves in thinking that we do.

~ Ends

If you enjoy my art consider making a very small donation to help me keep working. Through Patreon, you can give $1 (or more) per significant new work I produce, and cap it at a maximum of $1 a month. Click here or below to go to my account.

Any ads you see below here have nothing to do with me, and I don’t get anything from them.

I have a problem with markets and the commoditization of works of art. Then again, without this system perhaps many works would not have survived long enough to become part of public consciousness. Why are some works considered valuable and others not for reasons other than aesthetic appeal? Or does it have anything at all to do with aesthetic appeal? Is this just the way markets pick up & run with things – more for the benefit of the market itself?

LikeLike

Good points. I think you’re right about the market doing what’s best for itself. And, generally speaking, at least as applied to traditional art, aesthetics would give a great work a better chance of survival in the market. Nowadays I think that’s heavily skewed though, and it’s more about celebrity and reputation than inherent quality of the work.

LikeLike

Eric Wayne,

May I thank you for such a thoughtful, stimulating article about Vincent Van Goph. I really enjoyed reading it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. Glad you liked it. Check out the video version. I think it’s even better.

LikeLike