Appropriation is so old that adults were born after it was already passé. I know because I got my BA in art school in 1991 (23 years ago), and I’d already learned about appropriation, written some essays on it, and even done my own appropriationist work [there are even two appropriations in this article]. I “got” it back then, and it hasn’t changed much since. Let me share a few examples before I launch into a mini-critique of Richard Prince’s latest exhibition.

![Composition with bars of soap. 8 x 4 feet. [Acrylic, soap, Plexiglass, masonite board].](https://artofericwayne.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/soap-dishes.jpg?w=740)

If you aren’t sure what appropriation means in an art context, here’s a handy definition from Student Pulse:

Appropriation refers to the act of borrowing or reusing existing elements within a new work. Post-modern appropriation artists… are keen to deny the notion of ‘originality’. They believe that in borrowing existing imagery or elements of imagery, they are re-contextualising or appropriating the original imagery, allowing the viewer to renegotiate the meaning of the original in a different, more relevant, or more current context.

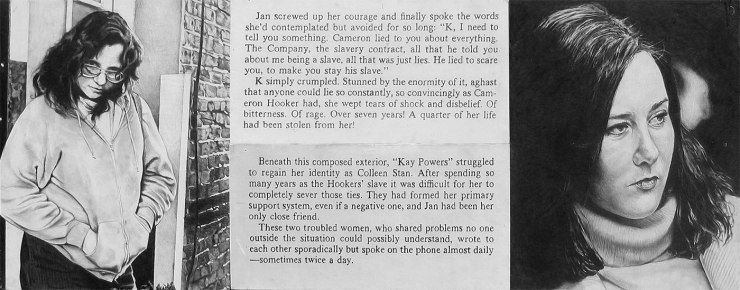

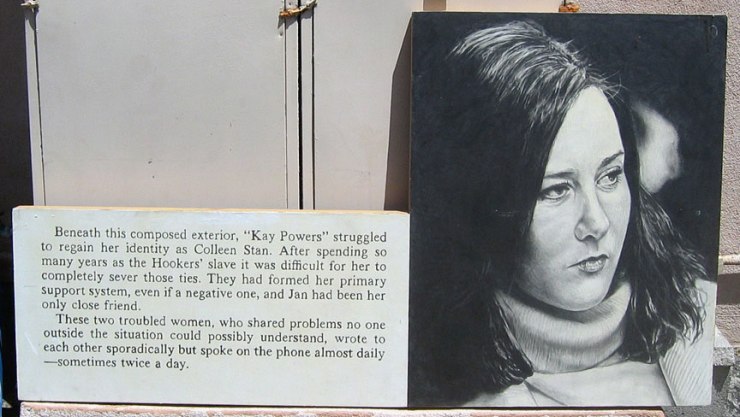

Above is a diptych, and each panel is “L” shaped so they are hung interlocking. It’s all done with mechanical pencil, and I think it’s 6 or 8 feet wide (can’t remember). The source was a non-fiction, pulp, crime paperback about a girl who was captured by a couple and kept under their bed for seven years. The text is just paragraphs which describe the “victim” and the wife of the abductor. The content is sensationalist, but the photos and rendering matter-of-fact. The photos and the text were both drawn in pencil, and both became subjects in the same light.

Here I was, over twenty years ago, appropriating photos and text from popular, low-brow culture, and recontextualizing them in a fine art context.

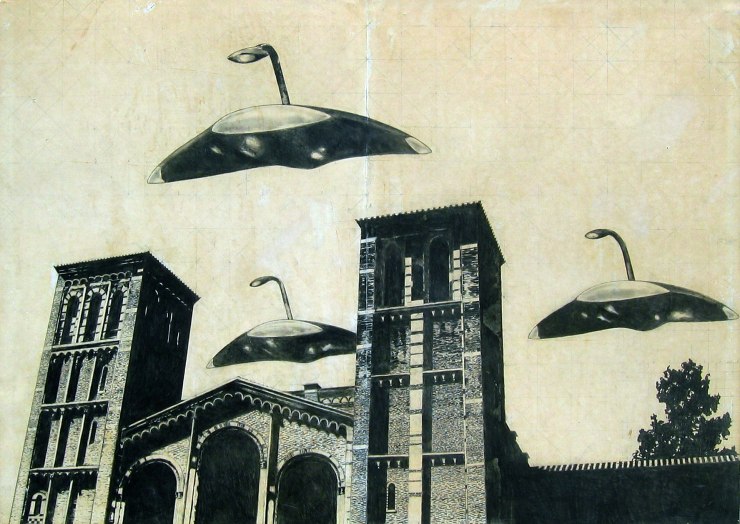

Not as pure as the appropriation from the crime paperback, in the image above I combined photos to create a new one. To get the ships I took photos of a TV while playing a video of War of the Worlds. This method of photographing media, as opposed to taking pictures of the outside world, is stock and trade of appropriationist, Postmodern art. I then used a grid system to make a large drawing of the Martian war ships flying over the university where I studied. I did some other appropriation-related work, such as making a very large text painting using stick-on letters painted fresh green (but I destroyed that one after getting a savage critique by someone who had an overarching agenda problem).

As you can see, I was well aware of appropriation in art when I was an undergrad, 23 years ago. And when I see appropriation done in 2014, I find it sort of nostalgic and comforting, like the rare times I went to eat at McDonald’s while I lived in China. It’s no more new or challenging than an abstract painting. In reality, appropriation and abstract art date back to the early 1900’s. Nevertheless appropriation is still considered more radical and controversial than abstract art, but this is largely due to a lot of people not accepting appropriation as worthy of calling art at all.

If we accept that appropriation isn’t itself challenging, but just another approach or technique an artist might incorporate, than Prince’s new works have a chance of being relevant because of his particular application of appropriation. Prince has essentially immortalized his own Instagram activity, along with the people he engages with using the app. Like Koons aggrandizing a balloon dog by enlarging it and putting it in the fine art context, Prince has done the same with the phenomenon of Instagramming. People’s selfies become fine art portraits.

A measure of how successful Prince’s “Portraits” are would be to gauge how viewing them changes the audience’s perception of their own Instagram activity. Does one come away rethinking their social media participation as “art”? Do we see the otherwise missed poignancy or beauty of a casual snapshot (even though Instagram is designed to produce just such an effect)? Or de we ponder the superficiality of the whole process, and how all our social media self-representation is so much artifice and masquerade?

Some critics have made a big deal about Prince including his own text comments, as if they contributed something meaningful. But they are all throwaway lines, such as “Now I know” in response to a girl’s selfie with her longish tongue stuck out. It’s not really what he says, so much as that he says something at all. His comment is like a signature, signaling that he contributed SOMETHING (though because of this convention he probably unintentionally positions himself as always getting the last word). And as artist Clayton Cubitt pointed out on Twitter, “Watching Richard Prince do Instagram is like watching your dad try to rap.”1

Through using Instagram, Prince tried to bring appropriation up to speed, and make it and himself seem contemporary, on the edge. With the technology available today, however, millions of people regularly take images and texts and cut and paste them into new contexts. We do that every time we share something from someone else on Facebook. When we put that cute cat photo someone took in Timbuktu on our Facebook wall, we recontexualize it within the Facebook paradigm (or matrix if you prefer). People were already taking screen captures of Instagram pages and redistributing them online in other contexts before Prince got the hot idea to showcase them in a gallery/museum framework.

Prince’s show was designed with the white-walled gallery space in mind. The gallery framework is part of the art, and inseparable from it. If you take the images out of the backdrop of the gallery, they return to just being people’s anomalous Instagram posts, and cease being “portraits” selling for over $40,000 each.

In both of the Richard Prince exhibit shots I shared above, I used Photoshop to replace one of the images with some other Instagram photo I grabbed from a Google search.

If you haven’t been to the show, you probably wouldn’t even notice the difference (can you guess which don’t belong?). That’s because it doesn’t f’ing matter which picture or which text, and that’s a bad sign for the art, because a sign of good art is that you can’t change anything without risking ruining it. Here, most any other Instagram snapshot would do, or any other one-liner. Prince can get away with this sort of arbitrariness though, because once any picture is presented within the Gagosian gallery backdrop and context, it becomes significant art. And this look of white-walled authority can be faked, and yet it still has that quality of importance about it, which shows that the authority is merely an association between the gallery space and the importance of the institution of art.

In today’s art world/market place, the gallery gives the art meaning, and not the other way around. Seen as most people access art today, in their social media feeds, Prince’s appropriations are visually indistinguishable from the original sources. The thing that separates them is celebrity and recognition within the contemporary art world/business framework.

This is very similar to something one of the Beatles pointed out back in the 60s about their celebrity status. He said that once you are on television, people treat you differently, and they don’t know how to act normally around you. What Prince is doing is merely the equivalent of putting someone on TV: he’s showering the Instagram photos with celebrity by putting them on the fine art pedestal. It’s really a collaboration between the artist and the art institution, which must be considered while contemplating the art.

In other words, it’s nothing. As a friend just pointed out, if the same pieces were shown in a different building, people would just assume there was a new service for printing out Instagram photos.

The bad news is that the death of originality is dead.

The good news is that originality lives on (as music continuously proves if you stop and think about it for a while), with or without the gallery/museum matrix.

~ Ends

- Sentence appropriated wholesale from: Richard Prince Sucks, by Paddy Johnson, for artnet news.Tuesday, October 21, 2014.

Here are some good articles I read about the exhibit:

- Richard Prince’s Instagram Paintings Are Genius Trolling, by Jerry Saltz

- Richard Prince’s Instagrams, by Peter Schjeldahl

- Richard Prince Sucks, by Paddy Johnson

- Richard Prince, New Portraits @Gagosian

.

Hi Eric

It’s hard to know how people like Prince can put a foot wrong, rather like people in high finance who get massive payoffs even when forced to leave companies they’ve brought to their knees. Notices about them (the former) seem to only ever describe the work / activity. Feasibly then that work / activity could be more or less anything so long as it’s similar to what went before.

I wondered – are the central images higher resolution than on instagram? Also, what was the involvement of the people pictured, and were they paid?

Jeff

LikeLike

From the articles I read, nobody was paid, and the resolution is the same as the original, other than being enlarged. So, apparently, they kinda’ look like crap up close.

LikeLike

Which all makes it tatty and exploitative. That’s the genius of it. What Prince has achieved in microcosm is a portrait not of those individuals but of a society in which we give ourselves away for a brief shot of fame. I wish I’d thought of that. This is why I live in hope that my extensive experience through volunteering will help me get a regular minimum wage job so I can pay my bills easier and he’s leaving trails of coke behind on Brazilian bushes when he comes up for a breather.

LikeLike

I read an article that made that same point about people giving themselves away online, and in so doing just making money for the people who own the venues they are using (in her case it was some forums), while not getting anything back themselves.

There’s another guy that argues that people should be paid for their online participation. I didn’t fully grasp his argument, though, as in regards to how that would work. Maybe one would get revenue for clicks generated on any and all sites because of them.

Personally, my online participation only costs me money.

LikeLike

Where oh where do you find enough time to write and do you art?! Let me in on your secret.

LikeLike

I think you said it best here, “In today’s art world/market place, the gallery gives the art meaning, and not the other way around.” It must be terribly frustrating for artist who have something to say/share/do to not have their gallery space because they are not part of Club 1%. When can we start protesting outside of art galleries? Or do we have to deflate every butt plug?

And here “The thing that separates them is celebrity and recognition within the contemporary art world/business framework.” Art is big business, just like US public education. Something has gone wrong.

LikeLike

I think that Prince’s added “throw away” comments are more than just needing to change something for the sake of changing something. I think they are actually quite harmful and sinister, adding a patriarchal tone to the series. These comments take away the voices and agency of the women in the photos. Not surprising for Prince, the vast majority of the images chosen are of beautiful women in provocative poses. Like the Girlfriends series, Prince has taken these women’s images and by extension their bodies, claiming them as his own art. He posts them from his own account with only his commentary shown, erasing whatever comments or context these women gave their posts. Presumably the women originally posted the photos themselves, but by replacing their comments with his own, Prince seems to dehumanize and objectify them. Not to mention that a lot of the comments have vaguely sexual connotations. The way Prince treats women’s bodies (in most of his work. Not just this series) makes me super uncomfortable. It feels totally nonconsensual and creepily voyeuristic. It’s one thing to appropriate balloon animals, but something else entirely to assert your voice, authority, and ownership over human beings.

LikeLike

I believe you are mostly correct. I’m not sure if I’d go so far as to say his comments were sinister, as opposed to just the predictable, middle-aged guy trying to flirt type of annoying bullshit. Yes, he seems to have missed the feminist boat, and the dock, and just be at sea adrift in unexamined patriarchy. I’d say his comments are not progressive, and maybe bass-ackwards, but I’m not sure about sinister. Could be. Thanks for the interesting and thoughtful comment.

LikeLike

According to Schjeldahl, some of the pieces are of Kate Moss and Pamela Anderson. I think you should have included this detail–it, all-and-all, doesn’t invalidate your points, but does add strata and may serve to make the RP shtick a touch more interesting: the contrast between already really famous/has been famous/only now famous because one has been stolen away to Gagosian, is arguably topos worth pondering.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You may have a point there, but, alas, Kate Moss and Pamela Anderson are so uninteresting and overplayed to me that I couldn’t imagine attaching any relevance to them anymore. That was perhaps an oversight. I guess it’s just hard to regurgitate yet again the cloyingly clichéd, even if that status is what gives it relevance.

LikeLike