The cringe-worthy legacy of celebrity, cheese-filling art critic, Jerry Saltz.

I marvel at the fact that for some reason, mysterious to me, people take Jerry Saltz, art critic of New York magazine, seriously.

The best I can come up with is that among the most famous living art critics, his name is easier to spell and pronounce than Peter Schjeldahl, who I also find critically myopic. Note here that while doing a Google search to make sure I spelled Schjeldahl correctly – I didn’t – the first result that materialized quoted Schjeldahl’s review for the New Yorker, in which he claimed Berthe Morisot, “the most interesting artist of her generation”. Doubtlessly he wrote this merely because she’s a woman, when you consider the competition included Manet, Monet, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cezanne, Degas, Cassatt, Seurat, and Toulouse-Lautrec. I’m a big fan of Morisot’s Impressionist paintings myself, but the competition was particularly stiff in the late 1800s. I have written that I vastly prefer Ana Mendieta’s multi-media art to the minimalist sculpture of Carl Andre, who she was married to, in which case I have no problem whatsoever praising female artists above men, but don’t do so gratuitously to make myself look relevant in the eyes of the overreaching political trends of the hour. Subordinating art to politics is one of the grand failures of the second-rate art critic, and Saltz is at least as guilty as Schjeldahl. But that is just one of his several categorical deal-breaking faults. If he were mighty Casey at the bat for Mudville, he wouldn’t just strike out, he’d shart, hit himself in the head with the bat, then vomit on himself.

Here I will outline 6 devastating strikes against Saltz, some mostly showing bad taste, but all philosophically bankrupt. They include:

- Said that art critics work harder than artists, and add another layer to art.

- Tweeted that Steely Dan is the worst music group, and because men like them.

- Called Francis Bacon a “cartoonist” and thoroughly dismissed him in a nasty hit piece.

- Compared Duchamp’s Fountain to the birth of Christ and the Copernican revolution.

- Declared Richard Prince’s appropriated Instagram posts “genius trolling”, and it gets worse.

- Praised attempts to censor and destroy art.

This is a long article, and the equivalent of 6 posts in one. You may want to read sections, and come back later to read others.

The pièce de résistance is his celebration of Duchamp’s ready-mades. I had to triple check to make sure he wasn’t writing satire. Nope. And then I realized that a lot of the opinions of this Pulitzer prize winning art critic are so ridiculous, and wrong, that they work better, and are more convincing, as satire.

Strike One: Art critics work harder than artists, and art criticism encompasses art.

Let’s start off with one that is unforgivable. Behold this Tweet.

“A good critic always puts more into writing about art work than the artist put into making it. The artist only creates. The critic must plumb that creation & also write creatively enough to deliver the full volume of the art while also creating a thing of beauty & clarity itself.”

Jerry Saltz

This may be the greatest face-plant in the history of art criticism. Saltz here subordinates art to writing about art, and declares such writing – and quite obviously his own – as possessing superior aesthetics and insight to mere art. You see, first the “good critic” performs a sort of alchemy by which he translates visual art into words, while the artist “only creates”. The critic plumbs the creation and delivers the full volume of the art into a written description. And then, beyond the feat of encapsulating the art in linguistics, Saltz takes it to the next level by adding the superior beauty of his own writerly flourishes, and the crystalline brilliance of his incisive analysis.

Pause and consider that Saltz’s understanding of art positions art as having less import and impact than his own writing, which the above quote is a prime example of. Some people will just see the problem as the faux-pas of Jerry insulting artists, and that being indelicate. My feelings aren’t hurt. My intelligence is insulted. His statement is not only wrong, but laughably so. It means that he doesn’t even understand that visual art is its own language which can’t be translated into words, let alone enveloped by them. You can no more capture a painting in words than you can a symphony. A literary critic working at least within the same medium of the written word would scarcely make such an abominable blunder. Jerry makes this mistake because of one of his other critical errors, which is to subordinate visual art to ideas, in which case he believes his distillation of those ideas and the added context he places them in creates a rich intellectual tapestry that is superior to the comparatively mute craft of fumbling with images, forms, or sounds.

Jerry’s position here indicates a profound and fundamental failure to truly appreciate art. When writing, as I am doing now, I am using a standard medium of communication. I don’t have to invent it. The medium is a given, and to use it I follow conventions that existed long before I was born. But an artist often has to invent the medium and try to wrestle meaning into it. I would dare contradict Saltz, and say that the artist works far harder to manifest his or her reality into a work of art than does the critic who expresses a linguistic idea in linguistic form. Truly great critics, like Robert Hughes for one, devote more of themselves to their calling than do average artists, that is true. Scope, understanding, an apprehension of reality, the ability to think rationally, and to communicate subtle and sometimes ephemeral feelings, impressions, and sensations in words requires dedication, persistence, and even bravery. And Robert Hughes would never have said that his book on the art of Frank Auerbach somehow encompassed the artist’s oeuvre, or that any paragraphs or pages devoted to a single image took more effort than making that image.

But in general, an artist – with the exception of some minimalist and conceptual works – will easily log in ten or hundreds of times as many hours into creating a work, or works, than will a critic in writing about the work. Jerry’s idea that critics work harder is preposterous and so wrong-headed as to be stupid.

There was a strong and wholly justified reaction to his Tweet, but Jerry had a comeback, which only makes matters worse for him.

“DO I have to say it again: A good critic DOES create! We do not ‘surpass’ a work. We create a thing in itself adjacent to another thing in itself. We ‘just create’ too. Un-knot your panties! No one said creating something is easy! So literal! You know I love you, artists!”

Jerry Saltz

What is this gobbledygook from someone who positions letters above art? It’s a gooey fistful of logical fallacies, for one. He starts off insulting us with “Do I have to say it again”. The problem was NOT that people didn’t properly understand his meaning the first time, and neither is he repeating what he wrote before. He’s furiously backpedaling, while still issuing insults to artists. He continues, “A good critic DOES create!” This is a straw-man argument: nobody said that an art critic doesn’t create. He’s the one who devalued artists, and now is pretending that he’s here to defend critics against a hostile diminution of his craft issued by artists.

Next comes a flat out lie about what he clearly stated: “We do not ‘surpass’ a work. We create a thing in itself adjacent to another thing in itself.” He said his art criticism is “more work” than artists put into their craft, and that they “only create” while he not only transforms their art into the higher realm of ideas articulated in linguistics, he adds an additional layer of eloquently written stunning analysis. That is definitely surpassing the work of the artist, and that is unarguably what he wrote.

And then there’s this gem, “Un-knot your panties!” I’ve never used that phrase, or the variations of it, in my life. I guess it always struck me as bullying and misogynistic. It’s the type thing you don’t say to someone you don’t know in a bar unless you are willing to take it to the mat. In any case, the issue is not people getting worked up over nothing, but that someone in his position of authority argued that art critics work harder than artists in just reviewing whatever art they address, and basically run circles around the comparatively diminutive intellects of artists.

What follows is, I gather, the level of intellectual gossamer we must pause and relish, reading it over and over while sipping fine wine, “No one said creating something is easy! So literal! You know I love you, artists!” Yuck! This is a brain fart, and he’s still talking down to artists. Artists here are supposed to be like overly sensitive children who he didn’t mean to tell that making art is easy, but just easier than criticizing art. And, since he didn’t use any metaphors or similes in his statement about the role of the art critic relative to that of the artists, there was nothing to take literally. And so we are served with an additional insult, that we can’t fathom figurative language, or irony, even though none was employed. Then we get the condescending paternal crap about how he “loves” us. Was the problem that artists didn’t feel loved by daddy Saltz? The question is whether or not he’s worth listening to as an authority on art?

Still trying to make this about how lowly artists couldn’t comprehend his lofty thinking, Jerry contradicted himself again: “Someone who writes about wine does not have to make wine. Ditto someone who writes about cooking” and “Criticism does not surpass art. I am arguing that criticism creates and it is a thing in itself that is adjacent to another thing in itself. Not better or worse.”

Two more logical fallacies. The first is defending himself against an apocryphal argument that you have to be an artist to critique art, though in his case this argument will have some legitimacy when it comes to his music criticism (stay tuned]. That is another “straw-man argument” (he presumes to defeat the actual argument of his adversaries by defeating another easier one, which they didn’t even make). The second part is along the same lines. The specific charge is that he said the critic works harder than the artist and offers additional value, not specifically that criticism is better than art.

He unwittingly set himself up with the argument that “Someone who writes about wine does not have to make wine” because he provided an outstanding example of where his argument about an art critic working harder obviously falls apart. Could we take a wine critic seriously who opined that he works harder when writing about a bottle of wine than did the winemaker in producing it?

Strike Two: Steely Dan is the Worst Band Ever

This is just a bit of low-hanging fruit I want to dispatch. I’ll get past his mindless Tweets and to his art criticism proper soon enough.

Here, Saltz, in an unrelated tweet, makes a good case for why a critic really would benefit from having some significant experience within the field of their criticism. I feel similarly about Steely Dan to the way I feel about the Bee Gees. When I was growing up, they were not my cup of tea. I liked prog rock and metal. But being a lover of music, inevitably I gradually was seduced by the sheer musicianship of songs which didn’t happen to be up my alley. A lot of people who didn’t like disco as kids — “disco sucks!” — probably can now appreciate what a great song Stayin’ Alive is. Similarly, many of us have had our Steely Dan moment of awakening.

One rainy day in a time when we still listened to the radio, I was lying in bed half asleep when The Fez came on. The lyrics, “do it with the fez on” struck me as stupid and annoying, but I was feeling too languid to do anything about it, and drifted in and out of consciousness. Coming back to, during an instrumental interlude, I was struck by the intricacy and sophistication of the music, despite finding the lyrics silly. I realized it was “good shit” and worth exploring, but that is not their best work.

The classic song, which deserves to be so, is “Do It Again”. And in the case of this song, the quality of the lyrics are even noteworthy. When I was an undergrad studying art at UCLA, I was force-fed a steady diet of radical and fringe ideas about art, some of which were bat-shit crazy. One of my more notable instructors is the most disgusting contemporary artist alive (or dead] — Paul McCarthy. Sitting through one of his classes could be a punishing insult to the intellect. Paul, at the time, was anti-painting, and whatever was the most extreme, and preferably atrocious art, was the best. On reflection, I can tell you that I am just too centered for that, and you can go too far out into the merely obscene and ludicrous.

I still remember one girl’s project, where she’d compiled a list of cliches and written them down in a spiral notebook. Part of her work was to read out the cliches, which became extremely dreary after the first few. Paul thought this was brilliant, and we spent a goodly hour or more discussing it as a group. I could kind of go along with her collecting those cliches, until she revealed she got them entirely from one book and just copied them down. It was the ironic act of copying them down that so impressed Paul.

It was against this sort of backdrop — which is also the kind of paradigm Saltz promulgates — that I heard someone playing “Do It Again” on the bus home to Van Nuys after school [I commuted to UCLA on the bus]. My reaction was, “Yes! Thank God! “, I was reminded that Art can be richly textured, aesthetically pleasing, complex, interesting, and rewarding. It doesn’t always have to be a punishing slap on the forehead.

The next day I had an impromptu conversation with a student I’d never met before, in front of the library. We discussed our majors and I mentioned some of my issues with the art program, and how my sanity was saved by “Do It Again”. As it turns out, he was also a recent convert to the band, and for the same reasons. We discussed the lyrics from memory. I quoted this bit:

“Now you swear and kick and beg us that you’re not a gamblin’ man; Then you find you’re back in Vegas with a handle in your hand.”

Ah, that’s the simple word I was looking for. The music was “intelligent”. And that was a relief. And it just so happens that Jerry picked as the worst band one that helped drag me out of the sand pit of fashionable anti-art nihilism. For worst band I would have selected dumb stuff like Huey Lewis and the News (think, “I Want a New Drug”), Sammy Hagar (“I Can’t Drive 55”], or Quiet Riot [“Bang Your Head”].

Why does Jerry think Steely Dan is so bad?

I gather men are a bad thing. It’s a criticism that has nothing directly to do with the music, and which many women chimed in to contradict him on. This giving primacy to politically fashionable talking points above art is one of Jerry’s Achilles heels, which he has more of than he has feet. And let’s all pause to hail the white man who throws other white men under the bus in order to make himself appear hip and relevant. This simple-minded-to-the-point-of-heinousness judging art by the biology of those who make it, or partake of it, is another of Jerry’s staggering weaknesses as a thinker, and as someone who is supposed to represent the interests of art. Meanwhile, he insults women because he is apparently unaware of Steely Dan’s reputation as among the most musically sophisticated bands ever, in which case he relegates females to not being up to appreciating complex art. Face plant!

And the whole reason I bring this up is because as much as I love music — and my tastes are very eclectic, including volumes of world music — I feel unqualified to write about music, even though I played in band in junior high through high school; taught my self to play the acoustic guitar on a basic level; and got A’s in my college level piano and music appreciation courses. I realize that I just don’t have the kind of insider, in-depth knowledge that performing musicians possess.

To see how a musician + music critic discusses music, which I am incapable of, you can watch Rick Beato explain why a Steely Dan song is great: What Makes This Song Great? Ep. 3 Steely Dan.

And for an analysis of Do it Again: here’s a video by Professor of Rock: Listening to this Classic 70s Duo Will Make You SMARTER

Jerry showed himself to be tone deaf, inadvertently dismissing as the “worst” a band that is understood to be outstanding within the genre, but was probably just being flippant, and wasn’t engaging in serious music criticism. I’ll let him off the hook as merely having a sorely underdeveloped appreciation of music.

Let’s now go deeper into his mean-spirited and embarrassingly clueless hit piece on Francis Bacon.

Strike Three: Francis Bacon is a Cartoonist

Curiously, like Saltz’s denigration of the high art end of rock music, his repudiation of Francis Bacon is also a rejection of high art, and this time in the history of modern art.

In recent years all the most famous art critics have come out to thoroughly condemn the art of Francis Bacon: Jerry Saltz, Jed Perl, Peter Schjeldahl, and Jonathan Jones. Would that a critic somewhere had the huevos rancheros to defend Bacon against what is clearly the institutional position. Possibly the best defense was lodged by yours truly. See my article from 2014: In Defense of Artist, Francis Bacon. Saltz goes further than the other critics in going after not just Bacon’s art, but the man himself. Here is the section from my article in which I addressed Saltz’s attempt to disregard Bacon.

Jerry Saltz’s Ugly Assault

Jerry Saltz, senior art critic and columnist for New York Magazine, similarly was unable to fathom Bacon’s sophisticated paintings, and instead focused on his private life. He opened his review of the Bacon retrospective at the Met in 2009 with a vicious personal assault:

Those who knew the artist—some of them his friends—described him variously as “devil,” “whore,” “one of the world’s leading alcoholics,” “bilious ogre,” “sacred monster,” and “a drunken, faded sodomite swaying nocturnally through the lowest dives and gambling dens of Soho.” Bacon was no kinder: He called himself a “grinding machine” and “rotten to the core.”

~ Jerry Saltz

It would be difficult to paint a more vile portrait of Bacon. The quotes are out-of-context or literalized, and it would be hard not to be biased against the artist, especially if one were at all judgmental, moralistic, or homophobic. There’s no mention that:

When Bacon died, the critic David Sylvester… described him as ‘the greatest man I’ve known, and the grandest’, and listed his staunch moral virtues: honesty, generosity, courage.

~ The power and the passion, by Peter Conrad. The Observer, Sunday 10 August 2008

And while we now have an image of the nocturnal Bacon stalking the lowest dives, we don’t imagine him having dinner (and often lunch) almost daily with painter Lucien Freud and his wife, or having at least one warm friendship that lasted decades:

Lucian’s second wife, Caroline Blackwood, laconically noted that she had had dinner with Bacon, ‘nearly every night for more or less the whole of my marriage to Lucian. We also had lunch.’ Lucian himself recalled seeing Bacon at some point virtually every day for a quarter of century.

~ Friends, soulmates, rivals: the double life of Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, by Martin Gayford. The Spectator, 14 December 2013

Saltz’s overt attempt to portray Bacon as a despicable sadist would have been less hideously ugly had he followed it up with anything other than a complete dismissal of the artist’s work:

For me, Bacon—who may be the only artist sharing a name with one of his main subjects, meat—has always been more of a cartoonist. He’s an illustrator of exaggerated, ultimately empty angst.

~ Jerry Saltz

I don’t think I’ve ever seen as (ironically) sadistic an attack on an artist. Would that Bacon were alive to have the opportunity to reply on his own behalf.

If there were any question of whether or not Saltz actually was up to the task of appreciating Bacon’s eloquent use of visual language, it’s eliminated in his assertion, “His early accomplishments are undeniable” (implicitly as compared to his later work). This is like saying, “Mozart’s teen’ compositions were his best” or “I like the early Beatles much better than the later stuff”. Bacon’s early work is more accessible because less complex, and it’s a bit crude and clumsy. He hadn’t yet developed his own voice or mastered his craft. His greatest paintings were actually mid-career, even if they were more impenetrable to the visually unstudied or myopic.

Bacon’s still evolving work of the 50’s is what most impressed the critic:

By the fifties, Bacon had hit his stride, painting what he called “figures … [in] moments of crisis … [with] acute awareness of their mortality … of their animal nature”—truths hauntingly self-evident in his large pictures of naked beefy men crouching in transparent cases, making love with or attacking one another; dogs cowering on dark streets; sphinxes; businessmen; and howling monkeys.

~ Jerry Saltz

I agree that Bacon’s work of the 50’s was exceptional, but he hadn’t yet developed the ability to balance strong colors; hadn’t found his core subject matter; and his backgrounds were still comparatively flat and angular. It is Bacon-lite for those like Saltz, who aren’t quite up to the heavier, more demanding, more evolved pieces.

Saltz claims that “Bacon’s formula had grown stagnant by 1965”, yet much of his best work was actually done after that, including the “lying figures” I shared earlier. It really does seem that the more mature work is over Saltz’s head. I do concede, however, that in his late years, Bacon became a bit of a self-parody, though I would say the same of many artists who live to be octogenarians.

Bacon… kept working his theme until it became a gimmick. The calculated pictorial repetitiousness and lack of formal development wear thin. Except for a number of fabulous portrait heads and the astounding Jet of Water—made in 1988, just four years before his death…

~ Jerry Saltz

If you have to make qualifications for “fabulous” portraits and “astounding” paintings made in his 70’s, can you really say his work “wore thin”? I also disagree about “Jet of Water”, which I find to be rather light, and one of the only Bacon paintings without a figure in it.

It’s just a bit odd, when I constantly hear that artists need a “signature style”, to see someone condemned for sticking with a general theme and mode of representation. Saltz reduced Bacon’s “formula” to a few stylistic devices:

He has no idea what to do with the edges of his paintings. Everything that happens in Bacon’s work happens in the middle of the canvas; at times you don’t have to look anywhere else. The bottoms of his paintings are always the same, too—a receding plane curves up at the sides, like you’re looking through a fish-eye lens or from inside someone’s eye sockets. He neutralized his paintings further by insisting they be framed behind glass.

~ Jerry Saltz

While there is a nugget of truth in this, most his paintings actually DON’T curve up at the bottom, and he often doesn’t put people in the center of the image. What is the use of saying “all” of his work follows a formula that it clearly doesn’t? See the gallery below for examples of paintings that neither curve up at the bottom nor place the figure in the center, proving Saltz flat out wrong.

And imagine if we applied the same standards to Pollock, Rothko, Monet, or even Van Gogh. Can we forgive Pollock for a career of flung paint evenly spread across a canvas, or Rothko for relying on soft rectangles of color, and then slam Bacon for exhibiting fewer consistencies within a broader range of techniques? Should we write articles about Van Gogh’s addiction to absinthe, whoring, self-mutilation, faux-angst, bad temperament, poor hygiene, and his repetitive use of thick brush strokes arranged in rows and arcs?

Most of the critic’s analysis is not of the art itself, but rather of the man, and it looks as though Saltz’s arm-chair psychiatry is full of contradictions. While he is sure that Bacon’s “angst” is “empty”, he nevertheless brings up experiences in the artist’s life that would produce angst in most anyone besides ironclad strongmen like Saltz himself, or Jed Perl.

On the day before his first Tate retrospective opened, in May 1962, Bacon learned Lacy [his lover] had been found dead, almost surely from drinking.

No, that wouldn’t cause REAL anxiety. Saltz continues:

Less than two years later, Bacon met George Dyer—reportedly when Dyer broke into his studio to rob him. For the next seven years the relationship rocketed up and down, then history repeated itself. On October 25, 1971, the day before Bacon’s retrospective at the Grand Palais in Paris opened, Dyer overdosed and died in their Paris hotel room. Bacon, then 61, was again devastated.

Still, nothing there to cause genuine angst.

See a new work I produced based on this incident in Bacon’s life, and read more about it here: New Art: Misfits of the Metaverse #5 [Francis Bacon & the Death of George Dyer]

Saltz’s mean-spirited assault on Bacon and his art contradicts itself and can best be understood by reading between the lines. As much as he wants to destroy Bacon’s reputation as a great artist, his evidence belies his conclusions. If you have to concede paintings that are “fabulous”, “astounding”, or bearing “truths hauntingly self-evident”, than you cannot say that the artist is a “cartoonist”. And if you relate tales of his living in the scarred landscape of the aftermath of WWII, being disowned, whipped, arrested, addicted to alcohol, humiliated in public, and surviving two of his lover’s suicides, you cannot say that his anxiety was “empty”. And if your list of his technical redundancies are broader than most famous modern artists’ arsenals of methods, you cannot accuse him of lacking stylistic breadth or innovation.

I shudder to think of what kind of art yet another conservative critic with underdeveloped visual literacy, and expert credentials, actually likes. Is it going to be more second rate, uninspired milquetoast? Below is the work of Katherine Bernhardt, about whom Saltz wrote, “[she] has been wowing me with her wild-style painting for ten years”.

The above painting is just horrible. I mean, if it was a parody of what really terrible art might look like, it would be OK, but this shit is serious. You might think this must be her worst piece. Think again. Below are two more of her masterworks.

THIS is what Saltz thinks is the real deal. Bacon is a “cartoonist”, but this is in his top 10 shows of 2013. Anyone who has been admiring this dreck for a decade has abysmal taste in art, and an overriding fondness for pure, unadulterated crap. Though, to give him an out, it may just be that the aging critic was soft on the young, female artist; and perhaps he was terribly flattered that she did a portrait of the photo of him flipping both birds in unison.

OK, She didn’t really paint that. I did. In ten minutes. With whatever paints were at hand. As badly as I could. Right, it doesn’t look EXACTLY like her shit, but, it was my first attempt. Give me another ten minutes and I might be able to make it even worse, which is even better. And you might be thinking that this kind of work is not really representative of everything the critic likes, and other things he likes must be much better. You are right, because it just doesn’t get any worse than Katherine Bernhardt.

Another one of his 10 Best Art Shows of the Year was the work of Eleanor Ray. Her paintings are definitely better, but not particularly daring, original, or anything else.

They are not bad though, especially if one likes bicycles as much as I do.

While these bikes are charming, I hardly think one could hold them up as among the best work of the year, or hang them in the same room as Bacon. Besides which, the second one was actually done by me (to fulfill an assignment) in my “Intro to Painting” class at Valley College over 20 years ago. This is comparatively safe and easy art. It is also much closer to beginner art, and all the more appealing to an underdeveloped eye.

The article continued, but that’s the segment about Jerry’s criticism. His views were symptomatic of the generally accepted paradigm of the day, which rejected aesthetics, skill, talent, sacrifice, originality, and art as a manifestation of an individual vision. Instead, people believed that everyone is an artist; anything can be art; skill is reactionary; painting is redundant; aesthetics are irrelevant; group identity is paramount; the purpose of art is fundamentally to express ideas in linguistics, and its highest calling is to bring about sociopolitical change. Francis Bacon then becomes representative of an outmoded and even repugnant kind of art, in which case milquetoast critics clamored completely onboard the latest wave of radical “theories” about art and politics, and sought to distinguish themselves as up-to-date and relevant by essentially rejecting high modern figurative art.

A cornerstone of this rejection of art in favor of the latest theories [and Saltz’s privileging art criticism over art reflects this same hierarchy in which ideas in linguistics triumph over art] is heralding Marcel Duchamp’s displaying everyday objects in the gallery/museum setting as successfully repudiating the art of his immediate predecessors, if not all prior art. His urinal, snow shovel, and comb, for example, were selected by the artist because they had no aesthetic appeal, and he was indifferent to looking at them. Duchamp’s stated goal was to “discredit art” and “kill” art as he felt religion had finally been rejected. It was a bold statement against artists, aesthetics, skill, talent, sacrifice, and meaning in art. Contemporary art critics feel compelled to celebrate icons of anti-art as the highest achievement in art, and this is probably the ultimate surrender and face-plant of a thinker who is ostensibly a representative of Art. Jerry Saltz, of course, joins the ranks of the anti-art intelligentsia, not with ambivalence or caveats, but as a full-fledged reborn member of the cult of anti-art/artist. And this brings us to his worship at the urinal.

Shart: Duchamp’s Fountain is the aesthetic equivalent of the Word made Flesh.

Before I launch into this, one really needs to know what Duchamp was explicitly trying to achieve with his urinal put on a pedestal in the gallery space.

“My idea was to choose an object that wouldn’t attract me by its beauty or its ugliness. To find a point of indifference in my looking at it.”

~ Marcel Duchamp.

The key word here is “indifference”. This is a thorough repudiation of aesthetics and visual art as a language and form of communication. The urinal is both mute, and visually innocuous. Let that sink in.

Duchamp wanted to eradicate art, as he felt religion had been rendered defunct by more modern scientific and philosophical understanding.

Just thought I’d share a graphic I made for my longer article about Duchamp from 2015 — The Big Bang of Conceptual Art — the full quote is below.

“I don’t care about the word ‘art’ because it’s been so discredited, and so forth… I really want to get rid of it, in the way many people today have done away with religion. It’s sort of an unnecessary adoration of art, today, which I find unnecessary. And I think, I don’t know, this is a difficult position, because I’ve been in it all the time, and still want to get rid of it, you see.”

~ Marcel Duchamp.

To put it very simply and directly, Duchamp is claiming that religion is just superstition, and so is art. There’s nothing really there. The icons of both religion and art refer to fantasies, in which case, any other icon would fulfill the same function. A urinal is what it is, and is all there is. Nothing transcends mundanity at its most banal.

His act of placing a urinal in an art gallery is a direct parallel to placing a toilet on an alter in a church. It says, “Here. Worship this! You might as well.” And worship the urinal we came to do, and to do so is the equivalent of worshiping a toilet as Christ, and calling it the second coming (which Saltz will do for art. I shit you not!]

Jerry falls hook, line, sinker, and worm for anti-art bullshit. This is a philosophical failure of the grandest proportions. There is no recovery for taking a prank seriously, and heralding a deliberately mute, aesthetically void, and utterly banal object as the most exalted example of that which it fails in its attempt to repudiate. It is the worshiping of a reproduction of the Mona Lisa with-a-mustache-scrawled-on-it as superior to da Vinci’s original.

As my graphic, above, illustrates, Saltz isn’t the only living art critic who falls for this nonsense: Martin Gayford does as well, and the list goes on and on, because believing Duchamp is the most influential or important artist of the 20th century is compulsory.

But let’s let Jerry Fawn over the urinal.

Duchamp may be the first modern artist to take God’s prohibition against “hewn” objects to heart. Fountain is not hewn or made in any traditional sense. In effect, it is an unbegotten work, a kind of virgin birth, a cosmic coitus of imagination and intellect.

~ Jerry Saltz, Idol Thoughts, February 21, 2006 (published in The Village Voice]

And here we have the second coming of art-Christ — a “virgin birth” issuing from “a cosmic coitus of imagination and intellect” — in the form of a piss-pot placed on a pedestal in order to ridicule art. Duchamp’s point was that art had become so vacuous, and art audiences and critics so gullible, that they would praise anything put on a pedestal in an art venue. And nobody has praised a urinal as Christ more eloquently, and with more conviction, than Jerry Saltz.

Oh, you think I exaggerate? Behold:

Fountain is the aesthetic equivalent of the Word made Flesh

~ Jerry Saltz

In case you don’t know what “the Word made Flesh” refers to, allow me to quote the Bible:

“And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth.”

~ John 1:14

The Word become flesh was full of grace and truth, and so, pray tell, was the urinal.

It is a manifestation of the Kantian sublime: A work of art that transcends a form but that is also intelligible, an object that strikes down an idea while allowing it to spring up stronger. Its presence is grace.

The presence of the urinal is “grace” just like the Son from the Farther is “full of grace and truth”. The reason I know that this isn’t so f_cking ridiculous that it proves Elon Musk was right that we could be living in a virtual simulacrum [I’m adding run by scientists with a cruel sense of humor, who are trying to test our credulity at every turn] is that we haven’t changed the Gregorian calendar to start over again in what was 1917 as The Year One PPP. [Post Piss Pot].

The Fountain is, according to Jerry Saltz, the art equivalent of God manifesting himself physically in the form of Jesus.

Just as Christians perceive Christ as the invisible made visible, Jesus said “He that hath seen me hath seen the Father,” so Fountain essentially says, “He that hath seen me hath also seen the idea of me.”

~ Jerry Saltz

Oh, we are NOT done. Not only is the fountain on par with God’s physical manifestation on Earth, it should be understood as a revolutionary intellectual achievement comparable to the greatest scientific theories. Here’s Jerry:

The readymades provide a way around inflexible either-or aesthetic propositions. They represent a Copernican shift in art.

~ Jerry Saltz

A Copernican shift in art?! Get this, placing a urinal on a pedestal is of the same magnitude of paradigm shift for human kind as proving that the Earth is not the center of the universe, but that it revolves around the sun! Don’t forget it’s also “a manifestation of the Kantian sublime” and the artistic version of the birth of Christ.

You might be thinking that Saltz is joking. Nope. Read the full article, Idol Thoughts. This view is echoed throughout the art world. And here’s Jerry in a Tweet making another claim of religious proportions for the piss pot.

Why, urinal is the “transubstantiation” of material into art.

In reality, the Fountain is what Duchamp said it was: a banal, mute object of visual “indifference” which he arranged to have exhibited in order to “discredit” art. Duchamp, were he alive, might be taken aback to discover his prank which was intended to kill of the transcendent in art, and absolutely any religious pretensions of art, is now written about not only in religious terms, but in direct reference to Jesus Christ. Keep in mind that the art he was discrediting including not only the Impressionists, but the Post Impressionist, and all current art up until 1917, including the likes of Cezanne, Manet, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cassatt, and even early Picasso. The urinal was a prop, or visual aid, for an argument against the ability of art to be beautiful, meaningful, transcendent, or to even be able to communicate as a language. It was issued a young Duchamp thumbing his nose at art, and it was also in terms of its intended meaning, not only wrong, but reflected an inability to fully appreciate art.

Imagine, if you will, a young writer who is bitter that a poem he submitted to a publication was rejected. [Note, Duchamp orchestrated this prank after his Nude Descending a Staircase was rejected from the Parisian Salon des Indépendants in 1912] Our young writer goes to an open-mic event, and when it is his turn to recite his poetry, he reaches the microphone behind his ass and farts. “That’s what I think of your poetry, and that’s what you deserve to get AS poetry” he barks, and storms off the stage. His fart is praised as the greatest poem of the century; as the literary equivalent of Shakespeare’s plays; as a revolution of thought equal to Einstein’s Theory or Relativity; and as momentous an awakening as the enlightenment of the Buddha.

This is not to say that taken in the aggregate, Duchamp’s collected works, including his Large Glass, Nude Descending a Staircase, and Étant Donnés are not significant, and don’t contribute to a certain trajectory of modern and contemporary art [including Warhol, Hirst, Koons, Creed, Levine, and Richard Prince]. I am saying that the Fountain is not a monumental work of art, but an outlandishly overrated prank, that on its own ultimately belongs in the margins or footnotes of art history, along with stunts like Robert Rauschenberg’s erased drawing of de Kooning (though other works by Rauschenberg deserve paragraphs proper].

The best I would hope for from a real art critic is to be at least ambivalent about Duchamp’s Fountain. One may find that it is retroactively relevant to art theories and practices of today (it was largely sidelined in its time], but that at most it can be seen a contributing to one branch of art-making, but absolutely does NOT repudiate any other, or visual language, aesthetics, skill, etc. Another way to put it is, yeah, there’s a link from Duchamp’s urinal to Warhol’s Brillo Boxes, but this doesn’t mean that Van Gogh’s art is repudiated, painting is dead, the author is dead, and conceptual art has permanently triumphed over, and replaced visual art proper. Rather, the tradition of appropriating usually banal objects and re-contextualizing them as art is just one branch or an evolving tree of artistic possibilities.

What does an art critic think is brilliant contemporary art if he believes the Fountain represented a great awakening for our species?

Hit Himself in the Head: Richard Prince’s Instagram ‘Paintings’ Are Genius Trolling

This is going to be more heavy cringe, folks. If you missed out on this art show, the celebrated conceptual artist, Richard Prince, exhibited blown-up, printouts of Instagram posts that he commented on. As usual, the review is an impressive piece of wordsmanship — enough, apparently, to fool most people — but the underlying thinking is shoddy. Saltz is like a guy who can explain his Chess moves in flowery language, and then get check-mated within three or four moves, after also losing his queen.

The first problem is in the title of the article — Richard Prince’s Instagram ‘Paintings’ Are Genius Trolling — which I quoted verbatim for the heading of this section, because it is itself a triple self-indictment. There’s the notion of “genius” at all, that “trolling” can be genius art (that his “trolling” is genius at all], and the biggest mistake is to call printouts of Instagram posts “paintings”.

Are these “paintings”? Saltz describes specifically how they were created:

Prince finds an image he likes, comments on it, makes a screen-grab with his iPhone, and sends the file — via email — to an assistant. From here, the file is cropped, printed as is, stretched, and presto: It’s art.

~ Jerry Saltz

That makes it a print. Not a painting. Derp!

There’s the sticky question of whether selling other people’s posts, which can include professional photographs, as one’s own art, is plagiarism. The sophisticated way to look at it is as follows: A mix-tape reflects a certain individual’s particular musical preferences, which they selected, in which case, if one were to record a comment after each song (ex., the only thing snappier than the beat is actual finger snapping!], then the entire mix-tape could be sold as the individual’s original musical arrangement. Yeah, I didn’t say it was right. I just said it’s the sophisticated view.

The artist chooses something and calls it art. That was Duchamp in the year 1 PPP. Then artists on the cutting edge decided they could re-contextualize not just mundane household objects, but kitsch objects and anything from popular culture [ex., the Balloon Dog].

You could also take photos of photos and claim the act of re-photography was a breakthrough, and the indistinguishable photos of photos were original art.

Prince’s “genius” move was to dust off some of the crust from this century-old sleight of hand and apply it to social media. And that would make him trendy, and Jerry, too. It would also make him remarkably slow on the upswing in understanding that people already re-share Instagram posts in other contexts all over the web as a general practice. Doing it physically in a brick-and-mortar gallery is like taking a screenshot of an Instagram post, printing it out on your home printer, cutting it out with scissors, sticking it in an envelope, and posting it by snail mail in order to share it with a family member.

Why not just share his favorite Instagram posts online? It was as easy to do in 2014 as it is today. In fact, in an article I wrote in 2015, I used Photoshop to switch out one of the images in his Instagram prints to prove that nobody could tell the difference and it didn’t really matter what the images were.

Below is the original

Copy-pasting imagery off the web, integrating it into another format, and posting it online is so easy, there’s no excuse for not just copy-pasting screen-shots of IG posts, and that’s if you can’t share them with live links.

But as “paintings” they might be higher quality, right? According to Jerry:

The New Portraits are all fuzzy and out of focus, reflecting the low quality of the digital files and iPhone lenses, not to mention what happens to this information when it’s magnified.

Jerry Saltz

As far as visual reward, one is better off seeing the imagery on a smartphone screen at a scale and format where it appears crisp and clear and the pixels are illuminated. Blowing up small image files looks cheap. But, of course, the visual experience need not be based on the quality of photographic imagery at all. It is worth noting that these are not gorgeous versions of people’s IG posts, which could have been done by asking permission, getting access to their original large-scale image files, reproducing the text, etc. I could do it all in Photoshop myself. Easy stuff.

However, as anyone who’s spent a week in art school knows, art today is all about the idea, and not what the art looks like in terms of aesthetic achievement.

Part of what makes this series so great in the mind of Jerry Saltz is Prince’s Instagram practice itself.

Prince scrolls or trolls Instagram feeds. For hours. He’s a real wizard of his tastes; as honed to his needs as Humbert Humbert was to where Lolita was in the house.

Jerry Saltz

Wait. What? Prince’s exploration of Instagram satisfies “needs” which somehow compare to literature’s most famous pedophile — courtesy of Nabokov’s 1955 novel Lolita — who obsessed over a 12 year old girl in the house he was staying in as a tenant. Let’s let Jerry off the hook as just picking a really bad analogy for someone searching out captivating content in a sea of uploaded imagery.

Prince is creating a rock-’n’-roll hip-hop ghetto patois of street dude, hipster, showman, Vegas lounge-lizard, flimflammer, voyeur, and hunter.

~ Jerry Saltz

“Voyeur, and hunter”. Oops! This really does smack of Humbert Humbert on the prowl. What was Prince hunting for, and what prizes did he find that Jerry also thought worth relishing?

Each is an inkjet image of someone else’s Instagram page — often a young girl posing semi-naked or maybe squatting to pee, laying on a gynecologist’s table, or taking a provocative selfie — and printed on canvasses measuring about six feet by four feet.

~ Jerry Salz

Got it. Funny, that’s NOT what my Instagram feed looks like. As it happens, I almost exclusively follow artists.

But what makes these inkjet prints of other people’s Instagram pics “genius” for Saltz? Ah, ’tis Prince’s witty comments.

But it’s what he does in the comments field that is truly brilliant, and which adds layers on top of the disconcerting images.

~ Jerry Saltz.

While I’m not surprised Jerry thinks text can be the best part of art [since he privileges linguistic communication above visual communication in visual art] I don’t see what he sees in the quality of the comments. Let’s look at the best example Jerry selects for our delectation.

Under a voluptuary in a white swimsuit, revealing her nipples, Prince comments, “Nice. Let’s hook up next week. Lunch, Smiles R.”

Jerry Saltz

I must be missing something. That comment is “truly brilliant”? It’s not offensive? It’s perhaps ironic, and in a way the “voluptuary”, Pamela Anderson, perhaps chuckles at, but that I don’t get?

It’s under a comment about her “home movies”, referencing a leaked private porn video. I’m surely not as “hip” as Prince or Jerry on celebrity popular culture — because it doesn’t interest me — so, I’ll have to give them the benefit of the doubt here.

Let’s go to the next example:

Under a girl in short shorts posed with legs wide on a motorcycle, he writes, “I remember this so well.” He then taps an emoji of a tent and adds, “glad we had the tent.”

I have the same problem here, and I can’t find an image of the original post to help me understand why it isn’t just him stating he remembers her in that position in a tent with him, which might be shading into a kind of textual sexual harassment. Right, and he was “pitching a tent”. Hilarious? Let’s move on to Saltz’s third pick for best comment.

Beneath a girl showing how long her tongue is, he writes, “Now I know.”

What the hell is Jerry talking about? These strike me as “dickhead” comments. Here are a few more examples I found online in an article about college students trying to sue Prince for using their images.

Like I said, I’m not “hip” to the popular vernacular, partly because I’ve lived overseas in China, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand for the last 15 years. But, uh, I’m going to interpret Prince’s comment on the first image on the left to mean that he is going from cool to hot for the girl. The second uses “ride” as a metaphor for sex, and he’s thanking her for the sex they had today, and suggests they do it again. The third … … I’m lost. I know what a “nut” is, but not “schmoo”, uuuuh, or at least not for sure. He may be responding to the person who said, “I’d beat”. Sooo, one guy would “beat”-off to the image, and Prince is sure his “nut”s would “schmoo”? Whatever it is, it’s sleazy.

So, I’m to understand that a sixty-something years-old artist writing sleazy comments on young women’s Instagram posts is “truly brilliant” and “adds a layer” on top of “disturbing images”. No. I don’t think so. Seems more like Prince needed to add text in order to say that he somehow altered the content, in which case it wasn’t 100% plagiarism. And whatever he wrote was, from the looks of it, the first dumb thing that popped into his head. Jerry puts a more positive spin on that:

by adding his comments, he not only leaves tracks of evidence, he reincorporates language into his work.

So what? How f_cking heady! Roy Lichtenstein was “incorporating language into his work” before I was born.

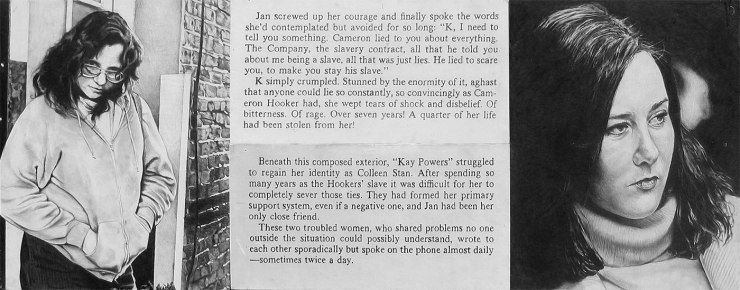

Shit, I “incorporated language” in my art in 1991 when I was an undergraduate at UCLA.

Wait a second. Taking text and images from popular culture and re-contextualizing them is “genius” contemporary art? I took these images from a true crime book, and it was 23 years prior to Prince’s Instagram “paintings”. I did several pieces using text, some with only text and stick-on letters. The point is that I GET it. None of this is new to me. I got an “A” in my undergrad “Art Theory” course. I have an MFA. Incorporating text into art is nothing new.

There’s this thing where no matter how many times conceptual art blandly regurgitates the same old tricks, it’s considered a perpetually fresh radical breakthrough. It’s not anything of the sort. In fact, These sorts of things have been done millions of times in colleges around the world, and anything a big name art star does has probably already been done at least a dozen times by undergrad art students. The “radical new” has been played out in the most ridiculous excesses. It is only a breakthrough if an art celebrity does it in the correct institutional space, and with the right marketing.

For example, when I was an undergrad, some kid stapled clear plastic bags, each containing water and a live goldfish, on the wall of the classroom. Whatever. We mostly talked about if it was cruel to the fish. But how different is that really to Mauricio Cattelan taping a banana to a wall a quarter century later? It’s not that the art idea is really valued for its philosophical import, but rather that an idea by a celebrity artist is fetishized as a commodity.

Saltz tries to explain away the charge of being “pervy” that has been leveled against Prince:

Finally, to the charge that Prince is a perv: For his entire career, this artist has culled and exposed underbellies and subcultures, making whole almost-invisible worlds visible. He has always culled marginalized personalities and lesser-known social zones. Now that the world has gone digital, these previously outsider factions are closer to the mainstream and always only a click away. By using Instagram and tapping into these self-revealing, self-documenting subgroups, Prince has eliminated the mediating middleman of the professional or fashion photographer, the advertiser, the packager.

~ Jerry Saltz

Lusting after Pamela Anderson does not represent a hidden, outsider, marginalized, sub-culture. Most of the stuff he showed strikes me as pretty mainstream. Erotic photos of young women?! Who would have thought of such a use for photography?! And the immediate access Prince gives us to the subjects by eliminating the professional photographer? He’s been sued multiple times for copyright infringement because the photos he appropriated in this series were the work of professional photographers. It would be more accurate to say that Prince creates a greater distance to the subjects by inserting his own irreverent, trivializing, and often sexist commentary, and then removing the images from a live online platform where you could engage with the actual creator.

Even if the photos Prince shared DID reflect subgroups or content that normies aren’t aware exists, that doesn’t mean it’s not perverted, nor does it justify it.

Saltz concludes:

If this strikes people as perverted, then Prince has always been perverted, and no argument will convince the squeamish otherwise.

The images don’t make me feel squeamish. The musty rhetoric makes my roll my eyes and the cringe makes my lip curl.

Why does Jerry fawn over this threadbare, pretentious twaddle?

There’s this:

(In truth, I spent last year wishing unsuccessfully he’d do me. Especially after I helped reinstate his Instagram page after it was taken down due to obscenity. Prince had posted his own Spiritual America, his famous appropriated Gary Gross picture of the young naked Brooke Shields.)

~ Jerry Saltz

Apparently, Jerry knew about the series before it was completed and hoped to be included, especially since he’d helped Prince get his Instagram re-instated after posting his appropriated image of a “young, naked Brooke Shields”. I just looked it up the piece in question to find out just how young Brooke was, and quickly clicked away. I can not reproduce that imagery here, nor would I want to. She was 10! Curiously, another critic, Carl Swanson, covered how Prince got banned and then reinstated after he personally made a phone call to Instagram: How Richard Prince Got Kicked Off Instagram (And Then Reinstated). I can’t imagine why critics are competing to take credit for getting Prince’s Instagram account recovered. In any case, Saltz and Prince are apparently on friendly terms, and their careers and interests intersect.

Prince has been called a dirty old man, creepy, twisted, a pervert. All of which may be true — but true in a great way, if that’s possible.

But there’s more:

I have already made several of my own screen-grabs of his Instagram grid and plan to enlarge and print them on canvas.

~ Jerry Saltz

Jerry thinks he’s an artist as well because he can traffic in this same kind of cynical art maneuver, that’s how easy this kind of art-making is conceptually and in terms of production.

Jerry sums up his article with this grand statement:

Prince’s new portraits number among the new art burning through the last layers that separate the digital and physical realms. They portend a merging more momentous than we know.

~ Jerry Saltz

That momentous and pretentious burning and merging has already happened in millions of cubicles dotting the landscape as people have routinely been printing out digital files for decades. I did it myself working for a bank in the graphics department, as well as when I was an assistant in the marketing department of a computer memory company. If anything, this work is nostalgic, hearkening back to a quarter century or more ago when whole populations got their first desktop computers, printers, internet connections, and started pressing ctrl+p to make physical copies of whatever imagery we wanted online. In fact, Prince was so behind on the internet and social media that he got the idea for this series after observing his daughter using Tumblr. He didn’t know what Tumblr was.

And if the conceptual ideas underpinning this series are of the last millennium, the aging man who prides himself on still being virile enough to lust after young women hasn’t been as cool and hip as he thinks since as far back as the Biblical story of Susanna at the bath [200 BC]. But, as students of art, we don’t need to read the story, we can just admire the painting Susanna and the Elders, by Artemisia Gentileschi, from 1610.

Vomited on Himself: Raised a Fist High for Censoring Art.

It was the season of the witch — witch-burning that is — and Saltz did not come to her defense. When the mob demanded the censorship and burning of art, Saltz threw his fist up in the air in proud allegiance. This is going to be a bit lengthy and in-depth because addressing this topic is treacherous, and I need to cover all my bases in order to clearly show why Saltz was egregiously wrong on this issue.

Preamble about morality.

I need to give a little background because this is a moral issue, dangerous territory, and a person with certain boxes checked on his birth certificate must tread very lightly, OR ELSE!! And I am arguing for what I believe is the sounder and more forward-looking moral and ethical perspective here.

I don’t really think that morality is that difficult. I like to say that the truth is often simple, but lies and subterfuge are infinitely more complex because they have to steer around the obvious truth and somehow convince us of a fiction. And so, morality, on a basic level, is also not that difficult, and if most everyone would honor very basic moral principles, we’d probably be doing a hell of a lot better. Even children can understand basic morality, which they need to do because the burden of being a conscious being with free will is that our days are filled with decisions, and actions based on them. It used to be we sought to judge each other by how we acted — or at least we knew we were supposed to — but now it’s a bit more complicated.

One tenant of morality that any child on the playground can understand is that whatever the rules are, they need to apply equally to everyone. It’s not about who the rule is being applied to or who is enforcing it; the rule itself and its application must be fair. If not, then it’s not justice; it’s just power that has to be respected!

I dunno, maybe because I briefly attended Sunday school. Even as a kid, I believed in the “Golden Rule”, and also karma. Growing up, I pretty much knew in my heart if I’d done something wrong or not, and I always believed in justice.

Let me just share a curious insight I had while teaching English at a university in China that perhaps sheds light on the opposite of justice. For reasons we could not fathom, the leaders of the English department would not tell the foreign teachers what classes they were going to teach until the night before the term started (whereas the Chinese teachers knew weeks in advance). This was very frustrating because we couldn’t prepare our lessons, and the stress would continue to ramp up as time ran out. We asked ourselves, “Wouldn’t they want us to do our job well and provide quality education to the students?” Nah. They wanted us to start off on the wrong foot, ill-prepared, unrested, and emotionally raw. One term, they didn’t give us our classes until after 10 p.m. the night before classes started at 8:00 a.m. the following morning. There was no reason for this, and one time I complained to the Foreign Affairs Officer at the university and got my schedule a month in advance, which affirmed that while they knew the schedule long ahead, they wouldn’t tell us because they knew how much that upset us to not know. This gave me an insight into power.

If a person in a position of power — a politician, for example — does what is right and appropriate, he is powerless because he always has to defer selflessly to what is ethically right for everyone else. Real power manifests itself in producing self-interested, or arbitrary and capricious outcomes. Hence, it was powerful to frustrate foreign teachers’ ability to do their jobs. We would know that someone was making our lives difficult on purpose, for no good reason, that it would hurt the students as well as us, and there was nothing we could do about it. THAT is power!

A little bit about my history with censorship of art.

When I was an undergrad at UCLA in 1990, my openly lesbian/feminist photography teacher gave a lecture about conservative politicians and commentators, from Jessie Helms, to Pat Buchanan, to Newt Gingrich, leading a war against art they found offensive. Jessie Helms in particular was vociferous in his opposition to the homoerotic photos produced by Robert Mapplethorpe, and Andres Serrano’s equally infamous “Piss Christ”.

Opposition from far right influencers resulted in a show of Mapplethorpe’s work at the Corcoran gallery being shut down. The House ended up deducting $45,000 from the NEA’s budget, which was the amount used to fund projects by Serrano and Mapplethorpe. Helms sponsored a bill that got passed, and succeeded in preventing the NEA from henceforth funding “obscene or indecent material”.

Mapplethorpe had already died due to HIV/AIDS at age 42, and so it just seemed heartless to me to shut down his show and erase his memory. At this particular juncture, George H.W. Bush had just launched the first Gulf War, and as it happened, my teacher’s lecture was not during my scheduled class, but in some other room, and as part of a moratorium on classes at the university in order to protest the war. Only myself and a friend showed up from our class to attend this voluntary lecture. It seems to me then that the hard, religious, conservative right was launching wars; alienating vulnerable people; and coming after artists and free artistic expression. I knew who the enemy was, and it wasn’t the civilian population of Iraq, gays who were dying of HIV/AIDS, or free artistic expression. None of those things threatened me.

In 1999 I found myself on the other side of art censorship again. Charles Saatchi’s Sensation art show, featuring controversial young British artists (YBA), had come to the Brooklyn Museum of Art. Since I happened to be living in Brooklyn at the time, I walked over to check it out. The most memorable thing was Damien Hirst’s shark tank. Not that I was exactly a fan, but it was hard to ignore. But the real controversy was over a painting of the Virgin Mary by Chris Ofili, because he had glued elephant dung to various parts of her body.

At first glance I could tell it was devotional rather than deliberately anti-religion, even if it included cut-out nude bodies, and one breast was a blob of elephant excrement. And it matters that concentric circles were painted on the dung because it signifies aesthetic integration. The resulting image worked aesthetically, and looked a bit like folk or outsider art. Doubtlessly there was some irony, a bit of parody perhaps, and the dung might represent earthiness, and African origin. That much was fairly obvious if one was familiar with contemporary art practices. I did have an MFA, so, perhaps I had a bit more background than Mayor Rudy Giuliani, who threatened to shut down the museum because of that painting.

After viewing the show I ended up arguing with some of the protestors outside the museum. “No, the artist didn’t smear shit on the Virgin Mary. It’s carefully placed… And that’s not the virgin Mary, either. It’s a collage and a painting…”. Didn’t do any good, and I went home, seeing once again that those who know the least about art want to exert the most control over it, and that censoring art was bad.

And here I have to admit that I do have a record of being attracted to that which I’m told I’m not allowed to see, or watch, or read. When a local bookstore in Los Angeles displayed novels which had been banned in the past, I took note that I’d read a goodly portion of them, though mostly unintentionally. And when it came to the art of minority or underrepresented groups, I’d also taken a keen interest. In my 20’s I preferred reading black authors such as James Baldwin, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, and my favorite, Toni Morrison. I read more of her books than any other living author. Musically, I was drawn to world music, and among my favorites were the Sufi Qawwali music coming out of Pakistan; Tanzanian traditional musician Hukwe Zawosi; Cambodian rock; and the gamelon music of Indonesia. Imbibing of art that didn’t issue from my immediate circle gave me a broader and richer experience and enjoyment of reality. Censoring and blotting out voices of dissent or alternative perspectives always struck me as repugnant and despicable because it forcibly narrowed one’s potential scope of reality.

And then this happened.

The world flipped its head on me in 2017, and censorship, smearing or villainizing artists, even burning art, became the cause célèbre of the highest, and most progressive good. The censors were now on the right side of history, and taking no prisoners.

This re-emergence of censorship on steroids — they didn’t just want to de-fund work, but to destroy it — broke all my core, childhood, playground-worthy, moral rules. 1) The rules didn’t apply, and weren’t applied, equally to all. 2) It violated the Golden Rule, because nobody would want their own art censored or destroyed because someone disagreed with them, misunderstood them, projected their own meaning onto a piece, or didn’t like their kind… 3) It didn’t feel right in my heart. It was like finding out someone was torturing prisoners, but for a purportedly noble cause. My first reaction would be very strong skepticism. This time, I was to learn, it was good people who were censoring the bad people, and demanding that their horribly offensive art should not exist.

What terrible thing had these bad artists done in their art to make it so offensive that it should be erased from existence? It would probably have to be some sort of racist art. And so it was, or at least that’s what it was accused of being.

A painting of Emmett Till, by Dana Schutz, appeared in the 2017 Whitney Biennial, which, of course, means it was selected by curators to appear there. This already sets up a problem where a work of art is both so vile it must be destroyed, while also being chosen as world class art because of its virtues.

At the time of the opening, Jerry Saltz praised the painting thusly:

If you think her work isn’t “political enough” see her thick, sluicing Open Casket, based on a portrait of slain teenage civil rights martyr Emmett Till and see if the idea of Black Lives Mattering doesn’t crash in on you.

Jerry Saltz, The 2017 Whitney Biennial Is the Most Politically Charged in Decades

From Jerry’s perspective, Schutz’s painting was a sufficiently political and persuasive vindication of Black Lives Matter. His attempt to jump on that bandwagon was miscalculated, however.

A protest appeared from within the art community itself, in the form of an open letter to the curators and staff of the Whitney biennial, as penned by radical activist artist, Hannah Black. The charge was that Schutz had no right to portray a black victim of white violence “for fun and profit”. She demanded that the painting “be destroyed and not entered into any market or museum”.

Her petition was initially signed by dozens of people , including artists, though after some consideration she removed signatures by white individuals.

As I wrote at the time, in my article Radical Activists Demand The End of an Artist’s Career:

We are at a moral crossroads. There are two competing moralities here. 1) It is moral to censor or destroy works deemed offensive, and take further punitive measures against the artist. 2) It is immoral to destroy art on unprovable and contestable interpretations both of art and the work of art in question (and reality).

In reality, the work was only really offensive because it was painted by a white woman, and one only understood why this was particularly egregious if one was studied in certain radical theories about art, race, and politics. Everyone else, from the Asian curators who selected the piece for the show, to Whoopi Goldberg and the cast of The View — Whoopi said the original protester needed to grow up — couldn’t even detect the problem.

For those of us who “got the memo”, however, the politics weren’t so arcane. Essentially, white people were all responsible and culpable for racism, hence blamable, in which case it is theoretically difficult or impossible for a white person to make genuine art combating racism when they themselves are inescapably guilty of the crime in question, and doubtlessly in denial. A white person addressing racism in art is, from this perspective, akin to a corrupt politician launching a campaign against corruption in politics. Dana Schutz then became, in the eyes of the radical activists, incapable of genuine compassion for Emmet Till, in which case her painting must be the opposite: a celebration of the crime of his murder, and in league with the historical circulating photos of lynchings. And this is how people genuinely saw her. Whites who were in the know, knew not to position themselves as morally and historically neutral witnesses to white supremacy. Rather, if they were woke, they’d know the right thing to do is to represent themselves as an indelible part of the fabric of the problem. The word of choice in various articles and publications was “culpable”, which means, according to Webster’s, “meriting condemnation or blame especially as wrong or harmful”.

But the story doesn’t end with protests against an individual painting. Behold:

In a letter from another group of radical artists protesting a later and unrelated show of Schutz’s work, at the ICA in Boston, the argument was made that the entirety of her work, by logical extension of the offense inherent to the Till painting, was a “violent artifact”. The artist was deemed guilty of “contributing to and perpetuating centuries-old racist iconography that ultimately justifies state and socially sanctioned violence on Black people.” and “erasing narratives of the continued genocide of Black and indigenous peoples.“

Did the painting, and the artist’s work in general, perpetuate evil to such a great extent, or to a lesser extent, or at all? Or was this a lot of “theory” and hypothetical conclusions based on a very one-sided interpretation of history, philosophy, art, sociology, etc. It was obvious to me that trying to shut down a show of work that didn’t even include the controversial painting was going way too far, and made Jessie Helms and Rudolph Giuliani look like fluffy kittens in comparison.

Art theory tends to heavily favor radical extremes. Few, if any, say that someone “went too far” in the realm of 20th century art. Saltz, as we’ve seen in my section on the Fountain, is a prime example of art-thought that as a rule, always rewards whatever is the most radical. But in the 20th century, we’ve witnessed the dire results of extreme political ideas when applied to living populations (Pol Pot comes to mind]. Experiments on canvases in artist’s studios, it turns out, are a lot less dangerous than radical hypothesis tested on peoples and geographies. And here we have a problem where the art world, because it [shortsightedly] is infatuated with radicality, allows itself to be infiltrated by radical sociopolitical theories and agendas which are much more dangerous than art, and pose a great threat to art. In my considered opinion, the way forward as a civilization is more measured, careful, and learns from history rather than abandoning it in favor of a radical new dawn. In this instance, we would do well to remember that defining people by their biology — which is based in scientifically discredited essentialism and biological determinism — is the foundation of racism, sexism, etc. Fixing people to their biology, along with employing censorship, in the name of the good, is a very unlikely step forward. But this is precisely what was happening.

I wrote an article about the attempt to shut-down Schutz show at the time [Radical Activists Demand The End of an Artist’s Career], but where was Jerry? True, this was a dangerous time to speak out against censorship of art, and I had serious reservations about doing it myself. And I did get a threatening letter from an extremist group dedicated to “ending white art” which ordered me to “quit pontificating”. Obviously, I argued for my second moral option in the quote I shared above: It is immoral to destroy art on unprovable and contestable interpretations…

When censorship of art reached its fever pitch, Jerry was doing the equivalent of Dick Cheney taking shelter in a concrete bunker on 9/11.

2 years later he came out on the side of those who wanted to destroy the art.

Open Casket, a small, widely contested painting based on the famous photograph of the mutilated Emmett Till — who in 1955 was murdered by two white men — became the center of one of the fiercest political storms in decades. One that found Schutz protested not by the right wing but — rightly — by the art world itself.

Jerry Saltz, Dana Schutz Takes Back Her Painterly Name, 2019.

The art world itself was “right” to “protest” the painting, according to Jerry Saltz. He had nearly two years to reflect on this, and he came out supporting censorship based on highly contestable radical theories that sought to demonize and punish an artist whose real crime, if we are going to be soberly honest, was to be insufficiently radical and progressive in her message. It is critical to recognize that these same people would have found her work equally offensive, sight unseen, based entirely on their theories and beliefs. In this case, it did not matter what her art looked like. She was a liberal, and obviously against racism, but her crime, as I outline above, was that she failed to implicate herself as necessarily culpable for current and historic racist crimes against Black and indigenous people, including genocide!

If you still aren’t persuaded that this is what critics were arguing, allow me to quote Hrag Vartanian, editor of the online art magazine, Hyperallergic [the bolding is mine]:

The artist appears to have absolved herself by refusing to implicate herself in the image, preferring to let the history of the image, and her painterly additions, make the case for her. Removed from culpability, she has instead used Till’s brutalized likeness as a way to explore painterly technique…

Hrag Vartanian, Hyperallergic.

The only reason the artist should be implicated and “culpable” in a ghastly and absolutely despicable racist murder, is the fact of her DNA at birth. This should give people pause. This is the pivotal notion on which the case against her art is built. She is necessarily guilty of the crime of the murder of Emmet Till! Vartanian made this abundantly clear.

“The image is particularly troubling because a white woman’s fictions caused the murder of the young man, and now a white female artist has mined a photograph of his death for ostensible commentary.”

Hrag Vartanian, Hyperallergic.

Not only did the painting never need to be seen for these same conclusions to be arrived at, had the identical painting been made by someone who belonged to a different biological group, the arguments would not hold. The criticism has nothing to do with the actual painting or artist. Both are merely concepts within the foregone conclusions of an extreme set of beliefs.

Saltz ended an article about Schutz’s new show with an attempt to align himself correctly with this kind of radical political belief:

What at first was mistaken as an issue of censorship, however, turned out to be far from that. The acumen of and ideas in the conversations made clear that much larger issues of representation were being called into question. In a time when the black body, indeed, all preyed-upon and marginalized bodies in this age, seem to matter less — when women, gay, Hispanic, trans people, and immigrants are demonized — the controversy raised the collective artistic and institutional political consciousness ever so slightly. To tremendous effect.

Jerry Saltz, Dana Schutz Takes Back Her Painterly Name, 2019.

An attempt to censor and destroy art, and to end an artist’s career because of interpretations projected onto her work, and because of her biology, is celebrated obsequiously by America’s most famous art critic as “tremendous”.

No, Jerry, clearly this WAS about censorship, and remains so, and the only person being demonized, quite literally, is a liberal white female artist. Just because an argument issues from people who categorically belong to groups which have been historically oppressed, suppressed, and marginalized, does not make it correct. The grounds for censorship, destroying art, and going after an artist’s unrelated show are far too thin.

I said this well enough in 2017, and I prefer to show that I’m not retroactively re-thinking this with the adopted wisdom of hindsight.

Dear irate protesters, chill out on the liberal artists who aren’t progressive enough for your tastes and slipped up when trying to be your ally. There are real assholes and murderers out there, not to mention people in real positions of power that engage in that old school variety of corruption that has very real and deadly consequences for everyone.

Dana Schutz is the least of our worries, especially because we all know she’s on the side of the good to begin with.

When you know someone is innocent or good, and you smear and vilify her anyway as a sacrificial scapegoat to the greater good of your eminently worthy cause, than people might wisely question whether your cause is indeed great, or even good.

Personally, I would steer well clear of a model of morality that censors art, has no forgiveness, no tolerance, and seeks to severely punish individuals for debatable, minor, and unintentional (possibly merely perceived or projected) transgressions. On top of that they exaggerate their claims to ridiculous proportions in order to make their charge stick, and don’t care if this demonization endangers their target.

It looks like they are looking for someone to make an example of. Are they are looking for [metaphoric] blood? That ain’t cool. It’s not playing nice at all.

This isn’t really about protecting Black and indigenous people from “state-sponsored violence” and “genocide”, which is something we should all agree with. Rather, it’s kowtowing to the hyperbolic excesses of extreme forms of radical theoretical academic discourse which aims to persecute, with no holds barred, convenient artist targets of their choosing. It’s not catering to the mob, but catering to a very thin slice of academia that presumes to speak for the general population.