You’re forgiven if you never heard of her. I never had either until an artist colleague emailed me an excerpt from her book, The Fraud of Contemporary Art. Almost everything by her and about her is in Spanish because she’s a Mexican art critic. Her biggest claim to fame is accidentally destroying a work of contemporary art when she set her soda can on it at an art fair. This wouldn’t be such a notable event if she weren’t an art critic, and if she weren’t so brazen as to appear at art fairs and tell artists to their faces that their work is garbage, or isn’t art.

The book excerpt is startlingly good, though I may be a bit biased because she’s come to some of the same conclusions I have, and which I’ve also written about in depth. My explanation for this is that once one sees through the fog of jargon and beliefs about contemporary art, the contours of the terrain of reality will appear similarly to various people. A lot of people have independently come to more or less the same set of conclusions. Avelina hones it all exceptionally well, and she’s got some real zingers.

Her overall idea is that contemporary art represents a belief system which opposes what had historically been recognized as art and artists, and she breaks it down into a fistful of unassailable tenets that the ideology at hand is composed of.

The first pillar in the belief systems is “transubstantiation”, by which she means when something ordinary is transformed into art merely by categorizing it as such. This, of course, goes back to Duchamp’s infamous “Fountain” – the urinal titled on its axis and presented as sculpture. She writes:

“The urinal as such did not change its appearance one iota; it is what it is, a prefabricated object of common use, but the transubstantiation, the magical religious change occurred at the whim of Duchamp.”

And she really nails it here,

“In this change of substance, the word plays a fundamental role: the change is not visible, but it is declared”.

Let me just add my two cents here. Visual art has its own inherent language, and is a unique form of communication. You don’t need to speak Japanese to appreciate Hokusai’s “The Great Wave” for instance.

But here, the language of visual art is muted, completely subordinated to linguistics, and what art IS, or means, is defined externally by words. Lesper writes,

“With the [idea of] ready-made [art], we return to the most elemental and irrational state of human thought, to magical thinking. Denying reality, objects are transfigured into art.”

But it doesn’t stop there. Art isn’t just defined by words, its relevance is also determined by them. Lesper quotes Arthur Danto, “to see an object as art requires something that the eye cannot give, an atmosphere of theory.” Here, you can’t tell if something is art just by looking at it, and is has no content that can be transferred to you through visual language itself. Academic “theories” must be employed both in order for something to be art at all, and then for it to have any relevance.

It is worth noting here that the current use of the word “theory” is not only misleading, but in stark opposition to its scientific meaning. In science, a theory is an explanation of natural phenomenon integrating a vast range of proven scientific facts. It is subject to the most rigorous scientific cross examination. In art, a “theory” isn’t even equivalent to a hypothesis in science, because a hypothesis must be disprovable via application of the scientific method. “Theory” in general academia is really just supposition, ideas, notions, and propositions. No vigorous counter-arguments need be countenanced, or even considered. To be valid, academic theories need only be popular, approved by authority, or instilled by power. “Art theory” sounds imposing, but as regards veracity, it is only “art conjecture”.

This absolute reliance on words to give art images meaning signifies the complete triumph of linguistics, at its most subjective, over visual intelligence, and visual language. Art is completely subordinated to any written or verbal statement about art, and the artist to the wordsmith. In the contemporary art world, rhetoric dominates art, and rhetoricians dominate artists. As Lesper put it,

“A work is legitimized by citations of Adorno, Baudrillard, Deleuze, or Benjamin. The works exist for a theoretical and curatorial discourse, denying all logical reasoning. This art refuses critical thinking, and demands that it be interpreted within the coordinates that accept it as art.”

The next tenet she addresses is “the infallibility of meaning”, by which she means that anything presented as art automatically has uncontestable meaning and import: is not as vacuous as it looks. Lacking any aesthetic value, such works are “awarded a philosophical value” instead: a value synonymous with the artist’s intent, which is further presumed to be necessarily “good in the moral sense”.

Lesper writes,

“What the artist does, starting with the action of urinating in public … has a good intention—it is an irony, a denunciation, a social or intimate analysis, and the curator adds to that intention a meaning that reinforces the arguments of the work as art.”

Our next tenet is “the benevolence of meaning”, in which she expands on the underlying belief that conceptual art is inherently morally good. Her argument is tasty enough to quote at length:

“The works, which physically appear unintelligent and devoid of aesthetic values, have great moral intentions. The artist is a messianic preacher, a Savonarola who tells us from the white cube of the gallery what is good and what is bad. It is curious that such works that determinedly assassinate art are also obsessed with saving the world and humanity. Empty of aesthetics but wrapped in great intentions, these works defend the environment, make critical statements on gender, denounce consumerism, capitalism, and pollution. Everything a television news program schedules is a theme for an anti-art work. However, its level does not exceed that of a secondary school newspaper. These works are not only superficial and childish; they also demonstrate a complicit submission to the State and the system that they falsely criticize. Theirs are politically correct denunciations. These works, supposedly rebellious, are carried out in the comfort and protection of wealthy institutions and with the support of the market. Hence, they make criticisms in a tone that does not displease the power or the oligarchy that sponsors them.”

Why yes, in order for contemporary art to be taken seriously it must be morally edifying in a progressive sense. This, again, robs art of its inherent value, making it a propagandist tool that must serve a certain sociopolitical agenda. The political interventions of an artist like Banksy don’t really say anything we couldn’t hear out of the mouth of a mainstream political commentator like Rachel Maddow, see in an ad by Nike, or hear in a political campaign speech by Hillary Clinton.

Next up is “the dogma of context”. You’ve all heard that art doesn’t take place in a vacuum. And here again, art is robbed of its own voice, because we are told it is a mute object defined by, and only understood in terms of the exterior forces of circumstance and expert interpretation. We are to understand that context gives art meaning, otherwise it doesn’t have any. What gives art context here is suppositions masquerading as theory, and more practically, the physical gallery or museum space. Lesper writes,

“The context par excellence is the museum or gallery. The object ceases to be what it is the moment it crosses the threshold of the museum … everything is coordinated so that an object without beauty or intelligence is art.”

“In great art” she argues, “the work is what creates the context.” Right again. In a great classical painting, the frame, or rectangular window separates the image from the environment, and when you peer into that window, you experience the context the artist himself manifested. The canvas is a portal into the artist’s reality, not an opaque prop that only gains meaning when it is projected on it from outside. Visual art is inherently a mode of communication with its own language, and conveys meaning without any intervention from curators or context forged in the altogether different medium of written or spoken text.

Our next tenet is “the dogma of the curator”. Lesper argues that the curator is ultimately a salesman, and the person who now is relied upon to give meaning to otherwise meaningless art. The curator selects examples of art to substantiate the theory, or the sociopolitical agenda he or she wishes to promulgate. Such a theme, as devised by the curator, is more important than the artworks that are selected to illustrate it. Lesper writes,

“In the brochures of the exhibitions the artists are no longer mentioned. Now the name of the curator is put first and it is specified that it is a project under the guidance of such and such an expert. If the name of the artist is not relevant to a curator, it is because the intellectual support of these works is provided by him and in practical terms, as the work can be whatever it is, what matters least is who makes it. The important thing is who directs it, who theorizes it, and that these theories are the structure of the work.”

She continues,

“… the curators refuse to exhibit great art, because such works do not need them there, since their rhetoric, their power, is sufficient. For the figure of the curator to have authority, it must be over works of this false art that is called contemporary. The other art, the true one, does not require it…”

Our art critic segues into the next tenet, which is “the dogma of the omnipotence of the curator”. She states that the curator’s ideas “are more important than the artist, the work itself, and therefore the art”. Contemporary art, she argues, has a symbiotic relationship with curatorial dominion, because “it is practically nothing” in which case “anything whatever can be said of it, any text, however disproportionate it may seem, can be imposed on the work.” She contrasts this with what she appreciates as real art, and uses Egon Schiele as an example:

“Writing speculative and rhetorical texts about drawings by Egon Schiele has a limit, no matter how much imagination and baggage is employed and emptied. The work says it all, it is itself imposing, and there will be no words that surpass it. Whatever the critic or the expert says, he does it at his own risk, because the work is compelling. The descriptions, the theories, although they go far, never do as much as the work. It is the limitation of the critic, the theorist, the historian. Great works are bigger than their texts.”

This is not a new dilemma for visual art. In the past art would have similarly been vulnerable to being subjugated to overriding external beliefs which relegated it to props that were useful for substantiating its own propositions. Consider a cathedral that is not only itself an architectural feat, but is filled with sculptures, paintings, and stained glass windows. The art shouldn’t call too much attention to itself, shouldn’t suggest its own inherent significance or an interpretation of reality other than that provided by the preacher/curator. Art is relegated to a kind of visual aid, the purpose of which is to convince people of a given set of beliefs.

Such a scenario is insulting to both artists and art audiences. Artists are not seen as capable enough to transmit their own content and meanings. And neither is the audience competent enough to interpret art directly by themselves. Instead, the intermediary of the curator does both, and for an ultimate goal that is extraneous to the art itself.

Next comes my favorite tenet raised by Lesper, “the dogma of ‘everyone is an artist’”. She starts with the assertion, ”Of all the dogmatisms that have been imposed to destroy art, this is the most pernicious.” And before I address her arguments, let me just ask you, is everyone a singer? I’m not. How about a dancer? I’m not that either. A novelist? Still not one. Why does everything require either some innate talent, or else hard work and long hours of training, except art?

“Democratizing artistic creation” she claims, “democratized mediocrity and turned it into the identity marker of contemporary art. Not everyone is an artist … art is the result of working and dedicating oneself, of spending thousands of hours learning and forming one’s own talent.” She goes on, “This dogma started from the destructive idea of ending the figure of genius, and has a certain logic, because, as we have seen, geniuses—or at least talented artists with real creativity—do not need curators.” I would replace the word “genius” with “virtuoso” because “virtuoso” strongly suggests a high level of skill achieved through extensive training – we often use it to describe classical musicians – whereas “genius” suggests a superior being, though she is not using the word in that sense.

She argues,

“Genius is not a myth. Education trains geniuses. Talent plays a part, but rigorous training and systematic work make the standards and results of talent higher, and consequently the artist’s craft and artistic level improves. We have had, and still have talents that can be called great: what is the intention behind demeaning them by generalizing and equalizing all people? Uniformity and equalization is the communism of art: it is the obsession that does not highlight what is really exceptional, in order to create a mass idea in which the only highlight is ideology, not people.”

There is something in there that rings true about the devaluation of the individual as an authority unto her or his self. Art must be understood via the contextualization of the authority of a representative of the institution, and must serve a positive moral purpose, or at least as envisioned by liberalism. You may have noticed that there isn’t a single example of a demonstrably politically conservative work of contemporary art that is heralded by the art cognoscenti. Not only is art denied its own voice or objectives, it must be harnessed to serve certain ends that would exist if the artist had never been born.

Lesper puts it thusly:

“The central figure of this false art is contemporary art itself, not its artists … With the invention of ready-made art, ready-made artists emerged. This idea that demeans individuality in favor of uniformity is destroying the figure of the artist. In the figure of the genius, the artist was indispensable, and his work irreplaceable. Today… all are dispensable and one work is replaced with another, because they lack singularity. The works in their ease and caprice do not require special talent to be made. Everything the artist does is … art—excrements, fetishes, hysterias, hatreds, personal objects, limitations, ignorance, illnesses, private photos, internet messages, toys, and so on. Making art is a pretentious and egotistical exercise. The performances, the videos … [all] appeal to the lowest standard of effort, and in their creative nullity they tell us that they are things that anyone can do. That possibility, the “anyone can do it,” warns us that the artist is an unnecessary luxury. There is no creation; therefore, we do not need an artist.”

Artists, she contends, are not just the victims here, but are themselves perpetrators, and traitors against art proper. Quote,

“The artist, to make matters worse, has become a low-ranking jack-of-all-trades. He touches all the areas because he is supposed to be multidisciplinary and does everything with little rigor … It is assumed that if the work is contemporary, art does not have to reach even a minimum range of quality in its realization. And if the work is done with quality, like the advertising objects of Jeff Koons, it is because it is made in a factory. This multitude of artists either do not do the work themselves, or are unable to do it well. Let the craftsmen do; they are dedicated to thinking. The reality is that, since their works are not art, the supposed creators are not artists. There are no artists without art. If the work is obviously easy and mediocre, the author is not an artist. Assumedly, artists do extraordinary things and demonstrate in each work their status as creators. Neither Damien Hirst, nor Gabriel Orozco, nor Teresa Margolles, nor anyone else on the immense and daily-growing list of people like them, are artists. And this is not what I say, this is what the works say. Let your work speak for you, not a curator, not a system, not a dogma. Artists’ work will tell if they are artists or not, and if they do this false art, I repeat, they are not artists.”

I agree fully with the second to last sentence. Art should speak for itself, just like we’d expect of a novel, and shouldn’t be an empty template for a curator to infuse the requisite content into. But I would not agree that Hirst and company art not artists at all. I would only say that the majority of their respective bodies of work are not visual art proper, but belong to another medium, or genre, just as music is not visual art. And while I agree that everybody is no more an artist than they are musicians, I see no reason why art can’t be made out of anything, and for a variety of creative ends.

I’ve done conceptual art, installation, and performance art, so I know there’s a creative challenge: there’s research, experimentation, trial and error, the hunt for inspiration. the waiting for the captivating idea, and so on. The media isn’t the issue, it’s what you do with it. I prefer to make visual imagery, but I am certain that just because you make drawings or paintings doesn’t mean you are a real artist, and just because you make videos or installations doesn’t make you a more relevant or up-to-date artist. What I oppose is the notion that visual art has been replaced by conceptual art, and rendered redundant. And I rail against the hijacking of art by “theory”, politics, and the marketplace. I reject as vile and insipid the muting of the inherent voice of visual communication, and reducing artists to second class citizens who need pseudo-philosophers, and connected curators to project meaning onto their work.

Lesper goes on to criticize university education for catering to the paradigm in question, and not providing students with a solid skill set, but instead wasting countless hours of instruction on ““conceptualization of work,” which is “the ability to make speeches about the objects that they produce”. She says,

“Conceptualizing and generating all kinds of rhetorical discourses does not produce artworks. Instructing others to do the artworks does not make us artists. Ideas are not art. Due to the distance I have as an observer of this phenomenon, I can appreciate the damage that is done to art, the disillusionment that the public experiences with these works; but what annoys me most is to see that students receive an education that is submissive to the market, an education that frustrates the talented and excites the mediocre.”

As someone with a master’s in studio art, I rather know too intimately what she’s talking about.

Lesper concludes her essay with this piercing condemnation,

“This misnamed art is a defect of our time and, as such, it means a setback in human intelligence. The endemic contempt for beauty, the persecution that has been mounted against talent, the contempt for techniques and manual work, are reducing art to a deficiency of our civilization. It is not innocuous to demean human creation to accommodate an ideology and its dogmas, allowing a domain of power that in other circumstances would be impossible to imagine. It is a reality that thousands of people who call themselves artists could not [create “art”] if this ideology had not been implemented. The aesthetic experience does not exist with these works; there is nothing to appreciate, evaluate, question. The work has become a rhapsody of theories and nouns.”

A simpler way to put it is that if you are looking for visual art to provide you something to train your eyes on, to delect upon, savor, and to slake your thirst for visual nourishment, you aren’t going to find it in most contemporary art. Au contraire. You will be given the equivalent of wet cardboard to a hungry diner. If you are looking for a visual manifestation of the artist’s unique inner universe, you can forget it. And, on top of it, those artists who would attempt such things were thwarted by the academy, sidelined, and treated as backwards pariahs not up to the great leap forward of radical conceptual art. I speak from experience. The art that Lesper prefers is considered irrelevant according to the paradigm she opposes. Each side declares the art of the other to either not be art, or not art worthy of any serious person’s attention.

I’ve had art instructors that were too traditional for me, and some too “radical”. Some were too political, and some seemed politically unaware. There are various and overlapping art paradigms, though the one which gave me the most trouble in the long run, was definitely the one Aveline Lesper is addressing here.

Some may see Lesper as the aggressor, but she’s at least as much the defender. While I certainly have condemned works by the likes of Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons, or Martin Creed as utterly derivative bullshit on a platter, I maintain that there’s always the possibility someone can do something fantastic and unexpected with any media or approach.

You can’t judge conceptual art from the criterion used to evaluate traditional visual art, and vice-versa. I think Lesper may be doing a bit of the former, but the art world at large has done a hell of a lot of the latter, in which case her damnation of it may be a very well deserved taste of its own medicine.

And now that NFTs are here, and twitter posts, basketball jump shots, and pixel art are selling for millions, any central understanding or appreciation of art that may have left a residual stain is now completely obliterated. It’s up to individuals to cultivate in their own minds their personal appreciation of art, and if they are artists, their own way of creating it.

You can read her full article here: The Fraud of Contemporary Art

~ Ends

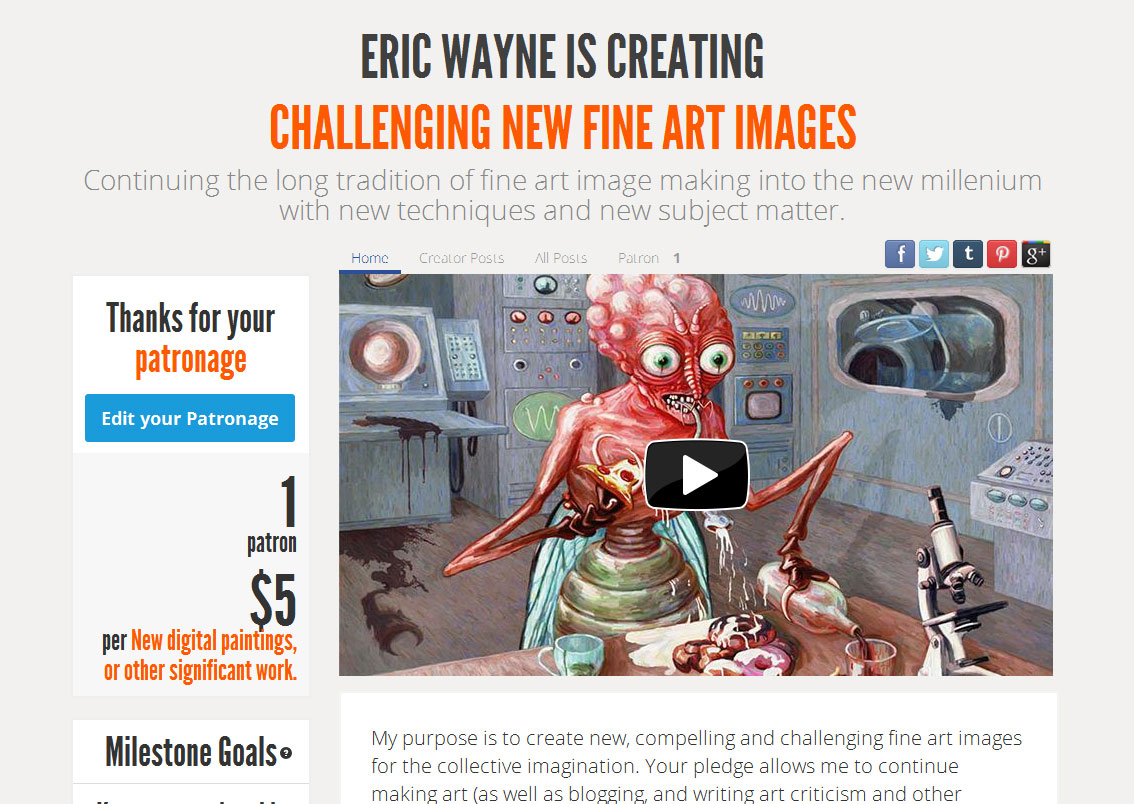

And if you like my art or criticism, please consider chipping in so I can keep working until I drop. Through Patreon, you can give $1 (or more) per month to help keep me going (y’know, so I don’t have to put art on the back-burner while I slog away at a full-time job). See how it works here.

Or go directly to my account.

Or you can make a one time donation to help me keep on making art and blogging (and restore my faith in humanity simultaneously).

Great post. Explains a lot, for those of us who are not artists.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Barry. It does give some perspective.

LikeLike

Excellent article Eric. I enjoyed reading every word. If a piece needs someone or something to legitimize it , or call it “art”, then there is something wrong here.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Summerhill. Yeah, you’re right. If you need words in order for visual art to have meaning, well, that’s the same as needing an explanation for a piece of music to be music.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had not heard of her either. What great stuff. And thanks for quoting her at length so often. As you said, zinger after zinger after zinger. She kept articulating points about the contemporary art landscape that resonated with thoughts I had not fully thought through myself. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Good to hear, David. I think there’s a lot of truth in what she has to say. Too bad most all her content is in Spanish.

LikeLike

Excellent criticism. I experienced the pleasure of seeing my long held views turn into words. It would be good to reclaim the word art for artists. I note that Irish artist Robert Ballagh has come to reject the word artist in favour of painter. This well placed criticism, including your own, might make artist a definition to aspire to.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Right, Shane. It’s time for artists to reclaim the word “art”. I can see why Ballagh used “painter” instead, though that excludes artists like Rodin. Nowadays, I tend to think it’s just for artists ourselves to reclaim art, and the world at large, well, it may be no use trying to change their minds. But at least artists don’t have to themselves be deceived.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Said tom wolf in 1975: “Frankly, these days, without a theory to go with it, I can’t see a painting.” Worse now, yes?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Was that from “The Painted Word”? I’d say that trend has continued, but I think something’s happening with the internet to destabilize the belief systems associated with brick and mortar galleries. Now, instead of whatever crosses the threshold of the museum entrance becoming art, there’s also whatever sells for the most crypto.

Art theory may be dying the death it sought to mete out on visual art proper. Installations and large scale conceptual art are at a disadvantage when seen via the portal of the smartphone.

Today’s younger artists are probably going to look more towards digital art than appropriation-based conceptual art. That would be my guess. People are making hundreds of thousands of dollars off of cartoon NFTs, with zero recognition from the corporate art world.

Theory may just have been a fad.

LikeLike

Yes, it was.

As in any other business, in art the new continually replaced the old, entrepreneurs become monopolists. An avant-garde persists, but the individual avant-gardists don’t. Art is what’s sells as art. Be it retinal, theory/conceptual, or NFT.

You are right. paleo-theory art was a fad like Orientalism or cubism. What’s weird in these “simulacrummy” days of digital ephemerality is that today’s avant-garde “art” (NFTs) no longer possesses a “presence in time and space” Its absence is its “aura,” If this isn’t neo-theory art I don’t know what is.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is satisfying to know that I am not alone in thinking that much of the art I see selling for millions is just empty, devoid of vision or personality. I did not have the words, just a feeling in my gut, and a sense of my own art being uncompromising. Or uncompromised?

At any rate, back to the old drawing board, Batman!

LikeLiked by 1 person

“In the brochures of the exhibitions the artists are no longer mentioned. Now the name of the curator is put first .… the curators refuse to exhibit great art, because such works do not need them there, since their rhetoric, their power, is sufficient. For the figure of the curator to have authority, it must be over works of this false art that is called contemporary.” – great stuff. A perfect reflection of our society at the moment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, I can see some artists just afraid of her critiques. As an English literature grad., in reading some artist’s explanations of their work, I just shake my head. Honestly, they actually don’t have to say much. The art work should speak for itself in whichever interpretation the viewer wants to make.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi! A couple of months ago – that long? – I left a comment on one of your posts & began watching your videos. Shortly after that I went “radio silent,” having sunk into my usual end-of-the-year-and-everyone-is-dead darkness. Still digging my way out. Your posts are helping. Why? Bec my first inclination in these rebirth times is to create but this year I’ve been flummoxed by indecision. What to do, how to do it, who will see, should I share, how to share, how much to care. Lurking here has allowed my heart to find its own beat again. Thank you for that. 🥰

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello. I know I’m awfully late to the party, but I wanted to clarify something at the very beginning of this post. It’s something minor and obviously not your fault.

Ms. Lesper did not set her empty can of soda on the “art” piece at the fair you mention, nor did she destroy it. Witnesses claim she set the can in front of it with the intention of showing there’s no way to tell the piece from literal garbage, and pictures taken in the moment show this to be the case. Shortly after that, due to the type of glass the piece was made of, it collapsed by itself. I also believe there was some bad blood between her and some of the organizers, but I don’t remember the details.

Sorry if I come off as rude or pedantic in this comment, it is not my intention. But every time I hear or read about the incident I feel the need to pitch in.

LikeLike

Uh, I wrote, “Her biggest claim to fame is accidentally destroying a work of contemporary art when she set her soda can on it at an art fair,” and “Lesper’s unintentional intervention.”

So, I certainly didn’t say it was deliberate. And I gather “Shortly after that, due to the type of glass the piece was made of, it collapsed by itself” means the art piece was “destroyed” in relation to Lesper placing the can next to it. The only thing I apparently got wrong is that she set the can not “on” the artwork, but rather, “against it.” Now, there I assume the can was touching the glass.

“On” versus “against” is a very slight difference, but “on” seems deliberately callous. So, I stand corrected on that small tweaking of getting the history of the chance even correct. Cheers.

LikeLike