An obscure artist was discovered, and quickly shelved.

These days most people in the established art world see art through the lens of politics, social issues, obtuse philosophy, rarefied art theory, and radical ideology. It took outsider, underground types of artists, cartoonists, and collectors — the variety the contemporary art cognoscenti turn their noses up at — to see the obvious with their own eyes. A visually literate person need only spend a minute with the drawing above to sense that Szukalski possessed extraordinary skill. And we all know skill is poo-pooed in favor of the grandiose idea: the IDEA of putting a shark in a tank; taping a banana to a wall; exhibiting one’s unkempt bed; canning one’s shit; and going all the way back to exhibiting a urinal tilted on its side. And this kind of drawing? Well, it’s considered fossilized dinosaur shit as far as the unwitting extremist ideologues of the art world are concerned.

There is a very large part of the art world that thinks the purpose of art is to further a revolutionary social agenda, and that anything that doesn’t accomplish that is at best irrelevant, and at worst upholding the status quo (and thus is part of the problem).

But for those of us who know how to draw, and can fathom the skill necessary to make something like the drawing above, it is, like it or not, far too good to ignore. Just pause, look at the strings in the harp that is the bow, note how their shadows fall across the forearm, and then are further cast onto the backdrop. That exacting level of intricacy is so accomplished that it’s intimidating.

This is Szukalski’s unique skill — and which he excels at more than any other I’m aware of — modeling imaginative forms in three dimensional pictorial space. In “The Ancestral Helmet” above, the artist places the woman’s eye precisely in the opened rear mouth of the face on the helmet. This is something a digital artist might accomplish with a 3D sculpt, after spinning it around in real time until the perfect angle emerges. But Szukalski, as a sculptor who learned to negotiate three dimensions in his teens, was able to rotate figures in his imagination, and then draw them not with line, but by laying down dots.

You can see the dots clearly in the drawing above.

Looking at just the images I’ve shared, if one hasn’t seen his work before, one would notice some other outstanding features. The figures are monumental, dramatic, stylized, and exaggerated. It would be impressive if they were naturalistic, but in veering from what exists, while creating the impression of space and solidity, he manifests his unique vision. That heroic vision, one would also sense, has an odd but familiar look about it. There’s an angularity reminiscent of Art Deco, but something grandiose, even propagandist about it. Something is being idealized, heralded as noble, the strong, the good, and perhaps the pure. And that’s where things get a little sticky. I detect a mid-century, East European feel about it, and that, in the extreme, raises some less than wholesome plausible connections.

There is even much evidence, in his obsession over his own wild theories, that he may have suffered from a mental imbalance.

The question of, “can we separate the art from the artist?” comes into play in Szukalski’s biography, though that may tend to a very predictable, knee-jerk reaction that doesn’t take into account the full scope or the man, or the art. It’s popular now to discover the worst thing we can about an artist, extrapolate that it permeates the fiber of his being and poisons his oeuvre like a cancer, and then we demand his works be purged from the canon. It may strike some as curious that in the realm of contemporary art theory, the notion of inclusion features an excess of condemnation and exclusion. We might do better to be less eager at the guillotine, and instead look for the good in the lives of others, and appreciate their accomplishments and gifts. What makes Szukalski great is specifically that his vision is so out of sync with the dominant strains of 20th century art, both in terms of style and content, but is nevertheless highly developed, compelling, and expertly crafted.

[People are a bit dim in recent times when it comes to the issue of art and morality. Their thinking on the topic is as nuanced as a refrigerator light: ALL ART MUST BE CORRECT, OR ELSE IT IS GARBAGE! For a take with a few more firings of neurons in the noodle, you can brush up on my article: Is Immoral Art Bad Art?]

The Documentary

I only discovered Szukalski a few days ago, while combing through the Netflix archive for something to watch. Everything seemed the same old stories, until I happened upon an art documentary about an artist I’d never heard of. Before I spoil the plot, I highly recommend this film. Here’s the trailer:

I had no problems with this documentary. It built in complexity; showcased the art very well; rounded out the character warts and all; and ended strongly on a human note. I can’t compete with it in a blog post. I can only add my own angle on it, and a few salient observations.

The film was released in 2018, and two years later the artist still hasn’t been recognized or promoted to the point where I’d ever heard of him. I checked online to see how my least favorite online art magazine (because it subordinates all of art and art history to a contemporary political agenda), Hyperallergic, covered it.

They didn’t. He is only mentioned in passing in articles about other topics [in the Crumb piece, “and works by forgotten artists (Gene Deitch, Stanislav Szukalski)”]. He is persona non grata. Who needs another dead white male artist, and particularly a painter or sculptor, in the canon?! Best to squash him by giving him zero attention.

How about ARTFORUM?

Shut out! Not even a film review. Nothing!

How about good old Art in America/Artnews?

No, again. Neither the film nor the artist merit any attention. They are not even worth shooting down. This oversight, however, is the shortcoming of these official art institutions, not the brilliant documentary, nor the amazing lifetime achievement of the artist. It isn’t that the material isn’t good enough — au contraire mes amis — but rather that the official art world made a decision to suffocate it, while tucking its own head up its posterior.

I mean, what fuckwittery is going on here? Sure, Szukalski was arrogant, eccentric, a white male artist “genius”, and there’s a little dark corner in his past, but nearly his entire works of drawings, paintings, and sculptures were destroyed in the Nazi bombing of Warsaw in 1939. He was buried in the rubble of his studio for 2 days. He went off his nut a bit (who wouldn’t under the circumstances?), but his skill is phenomenal, and the story is fascinating. But no, no sir and mam and their, let’s just flush the whole thing down to make room for the next performance/protest of Gauguin, Schiele, Close, Picasso, Waterhouse, Balthus, or whoever else it’s time to take down. That and there’s fruit taped to a wall to cover. The same year of the documentary, 2018, three of these publications covered artist Michelle Hartney putting her own placards next to Gauguin paintings in a museum, announcing his misogyny. Attacking great art is more important than discovering lost great art. The literary equivalent would be celebrating text on signs at a book burning as headline literary achievement, while ignoring a stack of books by a rediscovered novelist. The art world is less concerned with actual art than it is with constructing and controlling a self-serving narrative.

An article in Contemporary Lynx (I never heard of it, either) stated:

Szukalski … became a surprising hero for a bunch of mediocre post-hippies.

From such a lofty perspective, in which another neglected great artist, Robert Williams, is a mediocre post-hippy, than surely so am I, because I also think Glenn Bray, who rediscovered Szukalski, made a major find [and nobody worships Szukalski as a hero. Give us a break].

Sometimes it takes an artist to know an artist when he sees one.

Mediocre post-hippies kinda’ designates people who still love painting, or are real painters themselves. It also includes Ernst Fuchs, if you know who he is.

“When I saw the works of Szukalski. This was astonishing you know. What a sense of beauty and spiritual eroticism… Szukalski was the Michelangelo of the 20th century. And probably also of an age to come.” ~ Ernst Fuchs.

Painters?! Artists?! Phew! Enough of this antediluvian crap! Art has moved on! People are pinning protest placards next to paintings in museums, and strapping bananas to gallery walls!

Choice Bits

If you aren’t going to watch the film, can’t right now, don’t mind spoilers, or just like more input and reinforcement, here are some highlights from the documentary, including screenshots.

Szukalski was very opinionated about other artists, and it’s not apparent that he liked any of them.

Clever. Uh, I did a quick Google search to see if he coined “Pic-Asshole”, but, y’know, sometimes my mind doesn’t automatically go to the rock bottom, in which case it hadn’t occurred to me that all the links would be for pictures of assholes, literally speaking. I’m guessing he didn’t come up with Pic-Asshole, and I’m a Picasso fan, but I still like it.

This kind of thing is refreshing. Nowadays artists dare not criticize other artists (except for moral transgressions, in which case the gloves are off and the iron fist is on), for fear of damaging the viability of a gallery’s product. It’s bad business. And if you were to criticize the art of someone in a protected class, and you belonged to the unprotected class, you might next be seen in a suit of tar and feathers, humiliated in the public square, you cretin, you. Me, I miss when artists like Francis Bacon said Pollock’s paintings looked like “old lace”. Now it’s as if artists have nothing to say, or it all has to be upbeat pablum, or they just regurgitate the party line, comrades.

OK, it’s not just funny that he lived in Burbank, which is one of the more plebeian destinations in the world, but check out that signature. He invented his own design for the letters of the alphabet when he was a kid, and insisted on using it for the rest of his life. This reflects a lifelong sensibility of his, which is an insistence on being true to one’s inner voice, doing things one’s own way, and even discovering or inventing one’s own reality.

“If you want to create new things for this world, never listen to anybody. You have to suck your wisdom, all the knowledge, from you thumb. Your own self.” ~ Szukalski.

He did some Rodin-esque works.

Not Rodan, Rodin!

There’s a legend about how Szukalski learned anatomy, which is pretty disturbing, if it’s true.

It is my father. He’s been killed by an automobile. I drive the crowd away, and I pick up my father’s body. I carry it on my shoulder a long time to the country morgue. I tell them, “this is my father”. And I ask them this thing, which they did allow. My father is given to me, and I dissect his body. You ask me where I learned anatomy. My father taught me. ~ Szukalski

I don’t believe this story. Where would he have performed this dissection, and over what period of time would he have done it? And who has the stomach for that, especially when dealing with one’s own father. I think the artist was given to Dali-esque self-promotion, and wanted to be viewed as a mad artist extraordinaire. All that kind of stuff is arrogant bordering on megalomania by today’s standards, and his technical ability was no doubt achieved early, and through years of extensive training.

All this posturing, conceitedness, and delusions of grandeur may rub me the wrong way, but as an artist myself, on some level I see other artists as competition (in a good way), and I’m not going to fool myself by disqualifying competitors on extraneous grounds. The way to beat Szukalski is to render imaginary beings in 3D pictorial space better than he does, not to find some excuse to eliminate him from the competition.

I see art to a degree like MMA. A lot of people hate Conor McGregor, or Khabib Nurmagomedov, or scoff at the Brazilian jujitsu fighters that thank Jesus after winning championship matches. Scoff or hate all you want, they won. We can say that Floyd Mayweather, because of his abusive conduct towards women, is a bad person, but we can’t say he wasn’t, in his professional career, undefeated. To milk this analogy further, if someone’s kung fu is better than mine, my moral agenda doesn’t do anything to change that. And while skill is derided in art these days, as is the imagination, that’s because we’ve lost our eye on the ball. Ability matters in art. And I can admire someone’s ability even if I can’t stand them individually, which isn’t to say I dislike Szukalksi, just that it doesn’t really matter. Art history is not a record of saints, but of people who created great works of art. Morality is ir-F’ing-relevant in the arena of real art, and I consider myself a very moral person.

He did some really cool graphics.

There’s a collection of around 200 letters he wrote to one of his loves (I forget which), and each one contains an erotic drawing:

He was mainly a sculptor, though I am more impressed by his drawings, because it’s harder to translate a 3D object into imaginary pictorial space on a flat plane than it is to model it in physical reality (which is why Michelangelo’s sculptures are so much more realistic than his paintings).

“Art cannot be proper. Art must be exaggerated. Bend down until your spine cracks. You must exaggerate the likeness.” ~ Szukalski

And now the moment you’ve all been waiting for:

Szukalski, in the ’30s, put out some pamphlets while we was living in Poland, and was a Polish nationalist. They had antisemitic sentiments! Note above the insistence that Jews be removed from Poland. Indeed, at one point in his life, a kind of authoritarianism appealed to him, and he idolized Polish heritage. This is the type of snippet of evidence that justifies burning what precious little of his work remains, and purging his vision from our collective imagination. I wouldn’t do it, but I understand the tendency.

It is worth keeping in mind that not long after these pamphlets circulated to an estimated dozen or so people, his studio and nearly all his drawings, paintings, and sculptures were obliterated in a bombing raid on Warsaw. Roughly a fifth of the city was destroyed, and a quarter-million people died. He was trapped under the rubble of his studio for two days, and witnessed the Nazis machine-gun one of his sculptures. He may have learned his lesson, plus a couple more.

It’s perhaps too easy to fault people in the past for thinking or believing one of the popular strains of thought that ran through their communities. We tend to be more comfortable in our teens saying things like, “I would never have believed in witches.” We can all judge the veterans who committed horrendous acts during the Vietnam war from the comfort of our cubicles, safe in the knowledge we would never have burned down villages or raped the young women. This all presumes that we have an innate nature that is not constructed or vulnerable to the overriding beliefs of our times. I think it is more moral and enlightened to acknowledge that under completely different circumstances, especially overwhelming ones, we wouldn’t be the same people, and we would act differently.

Ask yourself if you are relatively in sync with the dominant beliefs and moral standards of the society you live in. If the answer is yes, than in the past, in certain environments, you very well might have advocated burning witches or expelling Jews from the homeland, since that was the cultural norm and perceived moral good of the society in question. If you are shooting potholes in the dominant narrative from the periphery, you might be able to make a better argument for how you would have behaved in another time and place. But if you follow the herd now, and we imagine your character would miraculously be constant, you would have followed the herd then. In the future, today’s high moral standard — with its twitter mobs, call-out culture, censoring of art, and overarching demonization of the west and colorless people — will rightly be perceived as ethically lacking.

As far as is apparently known, the artist didn’t harbor ethnic authoritarian beliefs in his later life, though he did insist he was a patriot of both Poland and America, and better the two than just one. In fact, he became obsessed with his own bizarre theories, such as that all people, language, and culture originated in Easter Island. He believed he’d discovered the original human language, which he called Protong, and which he uncovered through finding similarities between all other languages.

He spent 40 years compiling his extensive volumes of research into the true history of the people of Earth. This also includes his even more outlandish belief that there is a subgroup of people, descendants of the Yeti (yes, Bigfoot), who are the source of all evil in the world. No, it wasn’t racist, except against the Sasquatch, because even Winston Churchill was among the Yetizens, seeing as Szukalski viewed him as an imperialist.

I’m reminded of David Icke, and other conspiracy wingnuts, and that they share an underlying drive to figure things out for themselves, even on the most grand scale. What do you do if you have that inclination, but it’s already been done? Would that there had been someone to steer Szukalski away from this manic obsession, and back into art.

Friends say he was sane, but I’m not sure that they’d disagree that some of his screws could have stood a bit of tightening. In light of his patently ridiculous beliefs — which he dedicated half his life to developing, and with copious illustrations — we might excuse some of his earlier wrong-thought, especially if, as it appears to be, he outgrew it and adopted more humane, if lunatic, beliefs. He doesn’t appear to have harmed anyone. How is it possible for us to develop a broader and more just understanding unless we come from a narrower and less just one? And does this greater vantage of justice tolerate people making mistakes in their judgement or ability to measure reality?

At very least Szukalski was a consummate illustrator.

His sculpture is generally held as even better (though I prefer his drawings).

Even his personal encyclopedia of the genesis of all people and culture, in its monumental scope, is a sign of the magnitude of greatness. His work, taken in the aggregate, is an astounding achievement in art, whether it fits in with twentieth century giants like Pollock or Warhol, or if he held the proper beliefs at all times, or even sometimes (OK, probably never). His work is so obviously intrinsically excellent, on the face of it, that he deserves a place in the pantheon of art, even if he is, in the eyes of the contemporary art rubric, just another dead white male (and one with a record of some of the most reprehensible convictions!). Does art function to expand our horizons or to solidify an agenda? Clearly, as evidenced in the complete refusal from the established art world to acknowledge Szukalski’s prior existence, their paradigm is too narrow to accommodate him. For many of the rest of us, however, Szukalski ads to the scope of what visual art is capable of accomplishing, both technically and in terms of envisioning and manifesting one’s personal reality. Whatever his faults, and however and whoever might appropriate his art today for their purposes (there are some unsavory examples), I can’t and wouldn’t go back to the story of art in which his contribution is absent.

~ Ends

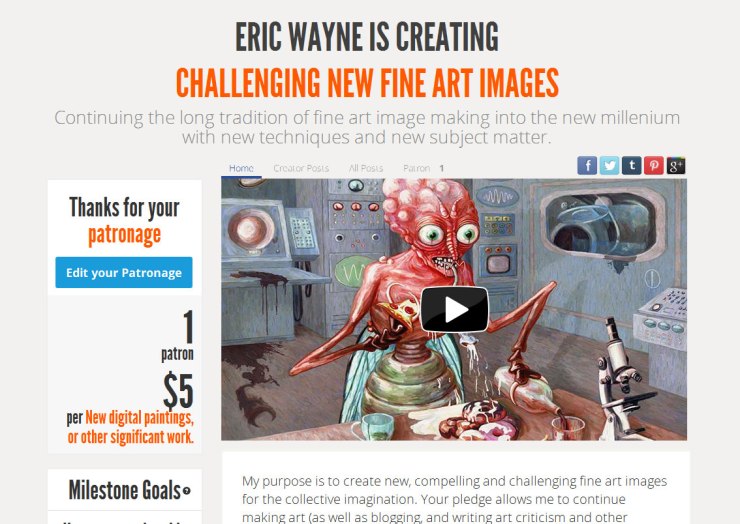

And if you like my art or criticism, please consider chipping in so I can keep working until I drop. Through Patreon, you can give $1 (or more) per month to help keep me going (y’know, so I don’t have to put art on the back-burner while I slog away at a full-time job). See how it works here.

Or go directly to my account.

Or you can make a one time donation to help me keep on making art and blogging (and restore my faith in humanity simultaneously).

Great piece Eric. You do art criticism very well. Love the bit about learning anatomy from his dad and your take on the story. And it’s refreshing you write with no agenda.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you enjoyed it and thanks for commenting. It’s a pleasure to be able to write about something like this when it is completely overlooked, or rather deliberately squashed by the established art world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I unknowingly came across his name in the late 90s when some of his artwork was used on a few releases by the band Burning Witch. Flash forward to today and I randomly decided to watch the doc on him not knowing who he was, but then I saw his art and put it together that he was the same artist use on the Burning Witch releases. The words “Fascinating person” really doesn’t do the man justice. Anyway, great article!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fantastic piece about a fantastic artist! Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your stuff is always so interesting and well-written.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was a very interesting read. Great bit of writing and as an artist, I hope someone would write this way for me some day. Bravo Sir!

I’ve never heard of this artist before either. I’d imagine there’s so many “great” artists that are overlooked it’d be mind blowing. I’ll be sure to watch the documentary about him.

Personally, I don’t think that being overlooked is necessarily a bad thing because artist’s “who make it” tend to become slaves to their own brand. Look at the many successful artists today or in the near past and you will notice their “enslavement” to their own brands, collectors, various art scenes, and art cultures & galleries. They become performers to expectations of their admirers.

In my opinion, being overlooked, is the freedom to make your art without the pressures of those outside influences.

You’re free to make the art as you please. I suppose it comes down to what an individual’s idea is of “becoming known” “being famous” or “making it” as their main goal in life.

Personally, I’m ok with being long dead before I’m “discovered” and I’m perfectly thrilled with those that take the time to understand the art I make now, and for those who purchase my works right now, I am grateful.

Sometimes, I must dance to a commission or two for a buyer here or there (because bills must be paid), but it’s always on my terms. I have total freedom of my art and that is a great feeling.

You did an outstanding job writing this bit. A lifetime of work and a gifted artistic ability should never be forgotten by the world. Little articles like this one, are what bring those forgotten artists into the light. Well done Sir!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hi. I’m glad you took the time to express your thoughts on the topic, and I think you are surely onto something.

You wrote, “In my opinion, being overlooked, is the freedom to make your art without the pressures of those outside influences.”

Yup! I wrote an article before about how the Abstract Expressionists were trapped in their signature styles, and how each one had a monopoly on a way of applying paint, and it was understood that the other artists couldn’t cross into their territory. Pollock is the easiest example. He was stuck in making those drip paintings, which I’d imagine might be a bit limiting after a number of years.

Artists, with few exceptions, are expected to churn out a product for their galleries. It’s imperative that the sanctity of the brand be maintained, and consumer expectation may dictate the artist’s options. Some artists, like Gerhard Richter and even David Hockney get away with switching up their style quite a lot, but most do not.

I don’t know how familiar you are with my blog or my work, but, try as I might, I’ve been so far incapable of sticking to one thing. In fact working in different approaches helps improve each other approach. But other artists, without even the pressure of the marketplace, like to stick to one style. It may have to do with an individual artist’s personality or character or something else. For me there’s an element of discovery that helps motivate me. And I also like to always be learning, and trying something new. A lot of my pieces start out as experiments.

So, you’ve nailed one aspect of being overlooked. But there’s a downside, and a very serious one, which is not being able to survive off of ones art, having to give up, and having to do some other far less meaningful thing which one is overqualified to do. Being crushed and consigned to ignominy has its hard edges.

I like to tell myself that if one is good enough, they can’t ignore you forever. Szukalski proves me partially right. There’s a Netflix documentary about him, and published material. On the other hand the establishment art world takes a big shit on him. And in the case of most artists, without support, they will never get good enough to not be consigned to history’s waste dump.

The art world now showers outrageous sums on a handful of artists while shutting out the vast majority who have roughly equal potential. The main criterion for an artist’s success is luck. Without the lucky break – being in the right place at the right time – the next factor is going to be dogged persistence in the face of dwindling prospects.

Just think of Van Gogh. The lack of recognition – and a rather astounding shut out considering his monumental popularity now – killed him.

Just one of Damien Hirst’s utterly formulaic and insipid dot paintings, painted by assistants, of which there are over 1,000, is valued at more than most artists will make in their lifetimes. The market is not only myopic, it’s cruel and insulting.

But there is a blessing to being able to do whatever you want because nobody gives a shit what you do, and you do it at your own expense. I, for one, would be happy to get table scraps – it’s my dream – so I could at least continue to make art.

Cheers

LikeLiked by 2 people

I cannot speak for all artists because we all come from a different walks of life and in many different varieties of life (hopefully completely different from each other in our actual work).

But I do know this about myself; I’m incapable of not doing my art. It builds inside me and whether or not I want to, I have to paint in order to feel balanced. Not painting leaves a pressure in me that at some point will burst out. I cannot change what I am. I was able to suppress my art for twenty years, so it can be done. I was a miserable S.O.B to boot.

I understand that it can be difficult to go to work to make money, then try to do artwork on the side because you have to pay the bills and then you’re tired completely exhausted from working, so no art gets accomplished. As the saying goes, “The cream always rises to the top”…. certainly without any work it doesn’t. But working and making art on your own time is far better than suppressing it.

I see “making a living from art” very different than becoming “known” or “famous”. Making a living at art requires hardwork, dedication, and a lot of sacrifices. You have to build a lot of outside relationships and for most of us, we aren’t sociable.

Becoming “known” or famous” is simply a byproduct of the latter (and an extremely rare thing when you view from the whole world of outstanding artists ((and even musicians) ).

I did watch the documentary about the man in your writing. Personally, I felt a lifestyle that reminded me much of Salvador Dali. Other artists in the documentary compared him to Michelangelo. I didn’t see those characteristics in his artwork.

Now for my critique (only an honest opinion not meant to offend anyone (I remember a time when that never had to be written)…As for technical ability, he definitely has that, but I felt an arrogance in his work and a quality I see often in a lot of artists including in myself, a sort of laziness with pride. Pride that keeps you from doing your very best work. I know this and recognize it well.

In much of his style, I can see the many influences of the 20s and 30s. I wonder if he has mental issue or if that’s an effect from using drugs? He also plays to his audience (whoever will listen), much like Dali did.

The mixture and blending together of cultures from Mayan, Indian, to Classical is seen throughout all his work. Blending isn’t an issue with me at all, but art critics of that time hated seeing what would work against the “brands” that were making the cheddar so to speak.

He said he never worked from models. I’m sure that part is true from his Classical over exaggerated perspectives. That’s what any good artist can do “exaggerate” the reality of an image. But they also embellish their stories too. It’s a quality that only good artists have. Put a checkmark on that.

But was there originality? Well, this depends on what you think originality is. If making images that nobody’s ever seen before is considered originality… then mission accomplished. But I view originality not only in the image itself, nor just it’s quality and materials, but in the processes that it took to make that particular image. There’s were I can sense the laziness within his work. I see that in my own work also (I’m working on it).

In that area, he lacked originality in my opinion. But if I did miss something important about his work, please let me know. I do believe I see why he was left by the artworld, and that’s because the world already had personalities like his…and many of them such as Dali and Picasso (and so many others).

I don’t really enjoy critiquing others artwork, but in order to improve my own work, I must realize what I lack myself in areas of originality, materials, processes, etc. so I can become better. 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been meaning to respond to this for a long time, but was busy with other stuff. The thing where you went 20 years without doing art – which I think probably millions of artists can relate to – substantiates my earlier point that most artists get shut out, because the few superstars (none of whose art I find particularly interesting) are showered with insane amounts of money, and everyone else scrapes by if they are lucky.

About Szukalski, you wrote: “As for technical ability, he definitely has that, but I felt an arrogance in his work.”

Yes, he’s arrogant. I said so more than once in the article, and also that the way to beat him is to render 3D illusioinary space better than he does, and from the imagination. His technical ability in that department in world class.

“In much of his style, I can see the many influences of the 20s and 30s. I wonder if he has mental issue or if that’s an effect from using drugs?”

I think it’s the effect of being born in 1893. That was the art when he was 27-37, and also when he had his early success.

“But was there originality? Well, this depends on what you think originality is. If making images that nobody’s ever seen before is considered originality… then mission accomplished.”

It can’t just be novel, because one could always go the route of making utter garbage, and nobody would have bothered to do that before because it’s insipid. We actually do get quite a lot of that in the contemporary art world. So, I’d add in that it needs to be done well, and he made his images and sculptures expertly. He’s mastered the particular skills necessary for his vision and kind of art.

“But I view originality not only in the image itself, nor just it’s quality and materials, but in the processes that it took to make that particular image. There’s were I can sense the laziness within his work. I see that in my own work also (I’m working on it). In that area, he lacked originality in my opinion.”

That’s a little vague. “The processes that it took to make that particular image.” I wouldn’t assume those processes were missing. I’m a bit of an “ends justify my means” guy when it comes to art, because ultimately the proof is in the pudding. Process is great for learning, and I have a lot of respect for it, but in visual art in particular the result is what really matters. His results imply that there must have been a process. So, I don’t know what you mean here.

“I do believe I see why he was left by the artworld, and that’s because the world already had personalities like his…and many of them such as Dali and Picasso (and so many others).”

I don’t think that’s it, exactly. The mid-century art world was obsessed with Abstract Expressionism, and positioning New York as the new center of the art world. Szukalski is obviously not a part of that at all, so he wasn’t in accord with the fashion of the day, the paradigm, or the narrative, at all. In other words, he didn’t fit the bill. But today, after being rediscovered, the problem is that he doesn’t fit in with the contemporary narrative, either. Today everything must be political, conceptual, and preferably issued from a young person who is in a minority group. There’s no room for someone like him, so he’s not even worth a mention.

Now, I don’t really give a crap about this or that paradigm, and I’m attracted to people who are outside of whatever the fashion is, but has a strong individual voice. They are a paradigm unto themselves. Now, Szukaski isn’t one of my favorite artists, but he’s outstanding in his own way. I don’t see him as equivalent to Michelangelo, either. But neither do I see Duchamp as on par with da Vinci, and that’s a comparison I’ve seen a leading art critic make. I don’t see Jeff Koons as equal to Michelangelo, and Koons argues himself that he is working in that tradition (by hiring someone else to make sculptures for him). Michelangelo is setting the bar too high. For me he’s an interesting curiosity, but what is most striking is his mastery of 3D illusionistic space, modeling, and lighting (color not so much at all).

As I said in the article, now that I know about him, I can’t remove him from art history. But there are other people like Robert Ryman (and his all white paintings) that offer less to me and have infinitely more recognition in the art world.

LikeLike

Another excellent rant. Where do you get the time?

I agree, he’s great, a neo-Blake in both talent and vision. But perhaps a little too Adolf Ziegler? Williams and Fuchs are worthy too. But I’ve heard of them.

There are so many artist out there, better than the famous ones. There seems to be a near total disconnect between expertise and insight on one hand and fame and fortune on the other.

I still like “Fountain” though, because: 1) It was the first. 2) its raison d’etre was childish spite not mature greed. 3) It was a kick in the butt the art establishment needed then. 4) It no longer exists.

But don’t mind me, I’m just another mediocre post hippie.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Right. I think there are a lot of great artists that are overlooked in favor of the ones that fit a certain narrative or two. Today there’s a real push to rediscover and celebrate previously overlooked artists, but provided their biology and output coincide with a certain agenda, which, simultaneously is invested in sidelining other artist who don’t fit the profile. There’s some good in that, but I’d prefer we just based our search on quality.

I sorta’ agree with you about “The Fountain”, with a few reservations. As a “prank” on the art world establishment, and a minor work that is a curiosity, I’m fine with it. As the greatest work of art of the 20th century, that changed the course of art and derailed painting, making it permanently redundant, I’m not. It’s all about proportion. I love Bob Dylan’s music, but I thought it was a joke to give him a Pulitzer Prize for literature. I think Bjork is alright, but, again, think a solo show of her music-related paraphernalia at MOMA was too much. I even like Yoko Ono in context, but don’t think her work merits nearly the attention it is given. And so it is with Duchamp. I like him as a minor artist who did some quirky things and made a few salient points. I don’t accept him as the grand anti-art master that finally nailed the lid of the coffin shut on actual visual art and artists.

Further, the art world he attacked was one he was already a member of. He was on the board of the “Society of Independent Artists” that put on the show that ultimately rejected his $6 submission, while accepting some of his other ideas, and nearly accepting “The Fountain”. The board also included Man Ray, Joseph Stella, and John Sloan. His work was a bit of a “fuck you” to the other artists, and implied that art was a thing to be pissed on. Duchamp’s criticism was that the exhibit was not truly open, because they wouldn’t accept absolutely anything, including something that trivialized everything else there. It’s a point. But did he really think it belonged in there, or was he just going after absolutism?

He particularly reviled the Impressionists for being “too retinal”, while himself being too cerebral and giving nothing at all to look at. I’d take Monet over Duchamp any day. Thumbing ones nose at real art has a certain adolescent, rebelious appeal. But in the long run, not only does he not live up the the quality of art of the people he attacks, he bores the living F out of me.

So, I’d probabably like him fine in the proper degree, if he weren’t crammed down my throat as the 20th century’s equivalent to daVinci (I have quotes to support that), and if he wasn’t the fulcrum used to sideline painting and destroy generations of painter’s prospects for the utterly false belief that conceptual art evolved out of and replaced visual art.

But, yeah, it was a witty joke at the time. I would have gotten a chuckle out of it. And I’m guessing that’s probably similar to your take, as we are both mediocre post-hippies.

Thanks for reading and commenting!

LikeLike

I watched the documentary on Szukalski a few months ago, fascinating life and his work is insane, in a great way. I also watched the documentary about Robert Williams around the same time, I’m a big fan of his style and I really love his attitude!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, is there a documentary on Williams? I’m sure I’ve seen some short things, but not a proper one. Hmmm. Let me look this up. “Mr. Bitchin”? I think I’ve seen it. I’ll have to watch it again though.

I just skimmed over it, and strangely, it’s his most offensive work that looks like his best technically. I’ve wanted to write about him for a long time. I think along with Hopper and Pollock, he might be one of the most “American” artists of the last century.

LikeLike

Very interesting. But on a positive note, I am sure that someday Art History will have to be rewritten, too many people having been ignored for the wrong reasons. You know there is a problem with the Art World when you realize that the “art specialist”, who does not create, thinks he knows better than the artist, who creates, what creating is all about! There is a big contradiction in promoting the idea that art can be anything and quickly dismiss anything that does not fit the current and accepted ways of “creating”.

But Art History shows us that everything change with time…

LikeLiked by 1 person

“There is a big contradiction in promoting the idea that art can be anything and quickly dismiss anything that does not fit the current and accepted ways of “creating”. ”

Glad you caught onto that. I wasn’t allowed to paint in art school, basically. You could do it, but it was considered ass-backwards and hopeless. There was the idea that “the purpose of art is to ask what art is” in which case, “painting isn’t art because it presumes to know the answer”.

Much of contemporary art theory is rabidly anti-painting, anti-artist, and it also happens to team up with postmodern politics, in which case it is also anti-West, and anti-colorless people. That’s just the package of belief one gets when one goes to college for contemporary art.

LikeLike

Thanks for introducing me to Szukalski’s work. I can appreciate the skill and effort he put into the graphics. Artists are forced to become rebels and resist if they want to create anything true, personal and honest. I myself have this urge to tape a banana to the wall. I don’t have any bananas. Would it still be sophisticated art if I taped a picture of a banana to the wall? –gb

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. Glad you likd Szukalski and appreciate his struggle.

The thing about radical, conceptual art is that it only countrs if an art celebrity does it. My next blog post is going to be about a guy who did the best piece of performance art ever but it wasn’t intended as performance art, and wasn’t received as it.

Obviously you were kidding about the banana (I’ve written a scathing review of that stunt), but, yeah, it doesn’t mean shit if an unknown does conceptual art. You gotta’ be part of the system or it doesn’t count.

LikeLike

I AM amazed that such Great Art was omitted from Art History, because of his origins and misguided views of

Youth but later on in his life he embraced people of all the nations including the Jews.

But just maybe he will added to the list of the Great Artists, when the likes of Damian Hurst will be put aside.

I am alas an artist also, alas not struggling anymore but that was not due to my success in the art world but by a

bit of luck. Szukalski was lucky to encounter Glenn Bray, di Caprio family so that post mortem the film was made

for fortune of the discerning ones !

your admirer,

Maryla Cohen

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, well, most people who write about art, or who decide what is significant art or not, do so from the standpoint of politics, ideology, and various ideas. They aren’t artists and often wouldn’t know a masterpiece from a botched fake. Recent history shows this to be the tragicomic case. They don’t care about quality, to the degree they can even ascertain it. What is important is how the art fits into this or that narrative of art history, or politics. If something is great (which they can’t even tell), but espouses the wrong opinion, or doesn’t seem to be a part of what they believe is the trajectory of art history, they disqualify it.

I would be surprised if Szukalski were to become more recognized in the official art institution, which is presently doing everything it can to eradicate “dead white male” art, traditionally skilled art, and certainly the art of someone who is suspect of being guilty of wrong-think. Ideological purity is the new litmus test of all art, and the most important qualification of an artist is her or his biology at birth.

It’s a rather sad state of affairs. However, as the film proves, real artists and art lovers will gravitate to genuinely good art, regardless of politics or whatever the iron fist of institutional art tries to pound into our skulls.

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing the movie link and your lengthy commentary–Szukalski’s work appears brilliant and deserves to be remembered.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you found Szukalski interesting. Art history today is too narrow and compartmentalized. It just simply doesn’t know what to do with him, so just ignores him.

LikeLike

Amazing post! I had never heard of him either. Thank you for the discovery of this great artist-

LikeLiked by 1 person

Most welcome indeed!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The key to understanding the moral character of Szukalski is contained within this qoute:

“If you want to create new things for this world, never listen to anybody. You have to suck your wisdom, all the knowledge, from your thumb. Your own self.”

He gazed upon his nation, witnessed suffering, correctly identified that the alleviation of said suffering was monetary reform, looked at who was in charge of money and said, “it’s them.” What do you think a man who’s mind is like this does when he arrives at control of the banks? Do you think he executes the Jews? Or, does, he then look from his new perspective, and say, “the problem is higher, it is upon the walls and boundaries of nations themselves, the relations between the kingdoms of Europe.” This is the man who could have stopped WW2, but the demiurge prevented it and placed a hawk upon the throne, throwing the world into disarray.

LikeLiked by 1 person