Broad Outlines

This is intended as a useful device for a very general categorization of visual-based art. The idea is to simplify something that is already hopelessly convoluted. There are inevitably grotesque omissions, outstanding hybrids, uncategorizable outliers, and genres I don’t address (such as folk art, outsider art, and comics…). But it’s worth thinking about the broad outlines, where different art loosely fits, and if you are an artist, where you might more comfortably belong, or where you might more profitably pursue your education.

We generally associate fine art with 19th century and earlier representational painting and sculpture; modern art with the mid-20th century; contemporary art with the last 50 years; and illustration with being an artisan. That’s so focused on chronology that it’s misleading. Duchamp did the first conceptual art a century ago, fine art and modern art practices are now timeless styles, and illustration can be sophisticated enough to rival the best art in museums. I’m using “modern art” and “contemporary art” as shorthand for the practices primarily associated with the modern and contemporary period, with modernism and postmodernism.

There are outstanding artists in each discipline. It’s mostly a matter of high artistic achievement, and transcending the medium. There is little to no relation between genre and artistic merit, and anyone who says otherwise is relying on a crutch to artificially elevate their own work, their paradigm, or worse yet, their bank statement above that of other imaginative beings expressing their own inner visions. These are distinct avenues of artistic exploration, not stages in artistic evolution in which one style is more advanced than another, and not rungs in a ladder of seriousness and complexity.

Illustration:

Today, illustrators possess the most technical skill, traditionally speaking. They are the ones who can draw and paint, use computers, and render an array of subjects realistically. However, all those skills are used almost exclusively for business purposes, and the final decisions are not made by the artist.

- The art here is a means to an end, which is usually advertising, accompanying writing, or for film or computer games.

- High level of traditional skills, based around drawing.

- Almost always representational.

- Doesn’t call too much attention to itself.

- Tends to (out of necessity) appeal to the majority, or lowest common denominator.

- Someone else ultimately determines what is made, and what is used.

- Uses computer programs and the most advanced technology.

- Standard skill-sets are a must, and there are objective measures of quality.

- Artists can make a living.

Fine art:

Traditionally, this is for painters who want to make their own imagery and have the last word on it. There’s more aspiration for meaningful content removed from commercialism, and the art strives to be aesthetically captivating. Fine art uses a mix of academic skills (perspective, anatomy, proportion, lighting…) and stylistic flourishes (how paint is applied, exaggerated or unrealistic use of color, brushwork…).

- Skill and aesthetics are both strong.

- Equivalent to a high-end illustrator specializing in painting, and working for oneself.

- Stylistic innovation, but usually figurative.

- This is the visual equivalent of literature: it aspires to have significant content and convey it through an equally captivating means.

- Strong tendency to reject digital art entirely in favor of traditional means (though this is neither necessary nor remotely appropriate).

- This style is not taken as seriously in the art world anymore, is considered backwards or craft, and it’s difficult to make money at it.

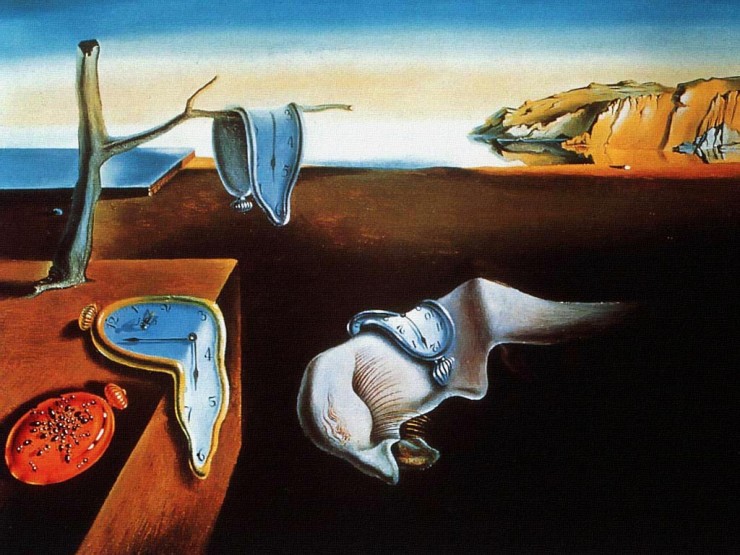

Modern art:

Art becomes its own subject, and paintings are often about color combinations, fields of color, gesture, or texture, rather than any subject. Modern art strongly believes in an evolution of art and the importance of stylistic innovations, in which case, if you aren’t making some contribution to the advancement of art, you aren’t part of the movement. While most pieces are non-representational, they are intended to be visually savored, and appeal to a sophisticated aesthetic sensibility. Traditional training may be relevant, but is not necessarily required, and frequently not evident in final results.

- Art for art sake.

- Aesthetics are paramount.

- Innovation is a must.

- High or narrow focus on elements: color, texture, gesture, scale…

- Content may only be in the paint or physical medium itself.

- Aims to advance the science of art.

- There may be a market for it if the artist is on the more aesthetic end of the spectrum and produces a polished product.

Contemporary art:

Here I’m addressing the conceptual end of the spectrum, and not just whatever is created in contemporary society. Traditional skills such as painting are not only absent, but reviled, and artists need not make their own work. The modernist notion of originality is similarly rejected, and a foundation of postmodern philosophy, along with a progressive social agenda, is usually required. Artists use any media or combination of media to produce works which arouse thought, provoke reactions, and start conversations. There is no universal or objective standard of quality, and your race, gender, sexual orientation/identification, nationality, and so on are entirely relevant.

- Anti-modern, anti-fine art, anti-illustration.

- Conceptual: the idea is paramount.

- Skill, aesthetics, and originality are secondary, irrelevant, or repugnant.

- Art is a prop in the service of conveying an idea, creating a reaction, starting a conversation, or spurring social change.

- Postmodern philosophy and familiarity with linguistics are a must.

- Sociopolitical agenda is inextricable from much of contemporary art.

- Race, gender, sexual orientation, etc. are of paramount importance.

- There’s no commercial application for contemporary artists, and slots in the museum and gallery system are extremely limited.

Breakdown

My table, above, is oversimplification with an anvil on top, but helps to see things such as that illustration and contemporary art have virtually no overlap, such that if you were to go to school for either you would be entirely unprepared for the other. I ranked approaches in relation to each other, so that while modernist painting surely requires some imagination, for example, it does not require the kind of visual imagination necessary for science fiction illustration. I’ll need to explain my specific use of the categories. The table addresses at minimal what is necessary for an approach, not what it is capable of.

Skill: I’m talking about traditional technical skills at making art, such as an ability to render images or sculptures realistically. While Jackson Pollock may have needed traditional training to eventually come up with his all-over drip paintings, you could learn to make competent drip paintings without being able to draw a passable eye, or even shade a cone.

Aesthetics: This is the beauty of the execution of the art. While some contemporary art is beautiful, the aesthetics may be borrowed, ironic, or are only important if they serve the purpose of furthering an idea. Contemporary art may also be anti-aesthetic, and only as visually appealing as is necessary in any kind of a museum display (too much beauty in a science museum would be a distraction, and this is also true when art is used to present ideas).

Imagination: I mean this in a very conventional sense, such as an ability to come up with fantastic imagery. Minimalism might require a leap of the imagination at some point, but an oeuvre of all-white paintings by Robert Ryman requires little additional power of visual imagination beyond a perfunctory array of applications of white paint. Contemporary art rarely if ever uses the word imagination, as the resulting art requires more critical thinking and being informed on various issues and philosophical underpinnings than any conspicuous exercise of the imagination. Fine art tends to be more creative about how it depicts something (Van Gogh sunflowers), whereas illustration uses more imagination in what it depicts (Kelly Freas’s cover for Queen’s News of the World).

Originality: This is the notion that the artist can come up with something stylistically, in terms of imagery, or content that is novel. Jackson Pollock is a prime example of this, where he is seen as innovating action painting. The post-impressionists are also commonly associated with approaches and resulting imagery that had not existed previously. Seurat’s “La Grande Jatte”, for example, literally attempted to engender a new way of looking at art. Note that contemporary art generally holds the position that originality is impossible — the author is dead — in which case it seeks to combine existing techniques, images, and artifacts (especially from popular culture or other disciplines).

Content: I mean a merging of subject and meaning, such as you’d associate with a poem. While illustrations will universally have subjects — consider Norman Rockwell’s infamous paintings frequently tell a story — there isn’t necessarily much meaning infused into the subjects. One could easily argue that non-representational modernist paintings have “content”, but not that it coincides with a subject separate from itself. Here, I’m just saying that relative to the other approaches, it has less literal content, not that it doesn’t have meaning, substance, or significance. The content of conceptual art tends to be in the more political and didactic end of the spectrum, in which case a subject and meaning are undeniable, while aesthetic substance may be perfunctory or absent. Ai Weiwei, for example, is known for addressing political issues in his art, such as in draping the columns of the Konzerthaus in Berlin with 14,000 Syrian refugee’s life jackets.

Innovation: This has to be relative to other art forms. Surely there is innovation in fine art painting, but not in regards to what else art can be besides painting. For the illustrator, innovation and originality are desirable, but only in smaller doses that will not call too much attention to themselves or detract from the product or other greater purpose they serve. While contemporary artists are anti-originality, they are not anti-clever, and so a smart artist can be resourceful and combine or recontextualize material in an innovative way. Sherrie Levine’s re-photographs of Walker Evan’s photos are virtually indistinguishable from his originals, which is the point, and that is that originality is impossible. However, we have the innovative act of presenting photos of photos in the gallery context as art. Jenny Holzer’s LED signs, Damien Hirst’s shark tank, Tracey Emin’s bed, and Koons’s assistant-painted reproductions of advertisements occupy similar territory.

Idea: Here I mean the idea of what the art is, not ideas expressed within the art. A novel may have hundreds of profound ideas within it, but the idea of writing a novel is so commonplace it hardly qualifies as an idea at all. I’m talking about art which is intended to convey a singular idea — especially about what the art in question, or art in general, is — or a set of ideas. You get some of that with modernist art, such as the idea of a color field painting, but the success of the art in question ultimately rests with the aesthetic quality of the artifact produced. A recent example of the idea being infinitely more important than the execution of the art is Maurizio Cattelan’s banana duct-taped to a wall at Art Basel in Miami Beach. The physical art is perishable, and made from worthless materials, nevertheless the sculpture made worldwide art headlines because of the controversy it provoked.

Politics: This, again, is a comparison. Surely fine art has addressed politics — Goya’s Disasters of War comes to mind — but only contemporary art frequently makes politics synonymous with art, if it doesn’t make art subservient to political causes. This, however, is a trend of the last quarter century, and the Koons Balloon Dog I used as an example in my lead graphic has precisely nothing overt to say about politics. It is not an exaggeration, however, to say that in contemporary art discourse all art is seen and evaluated through a sociopolitical lens. The most recent trend is social activist conceptual art by marginalized persons. Sonya Boyce, for instance, arranged to have John William Waterhouse’s Hylas and The Nymphs removed from the Manchester Art Gallery in order to challenge historic sexism in art. In it’s place museum goers saw a text challenging the Victorian fantasies of women as either “passive decoration” or “femme fatales”. There was additionally a table with sticky notes and writing utensils so the public could participate by sharing their own opinions. The work gains added street cred because the artist is a black woman.

Straddlers, hybrids, anomalies, and fakes

Kerry James Marshall

While there are strong general trends, artists can be all over the map relative to the genres they loosely fall into.

We might think of Kerry James Marshal as a contemporary artist because he’s alive and working now, and because of his political content, but it would be much more accurate to see him as a fine artist whose technique falls between fine art and illustration, and who addresses black identity as his subject.

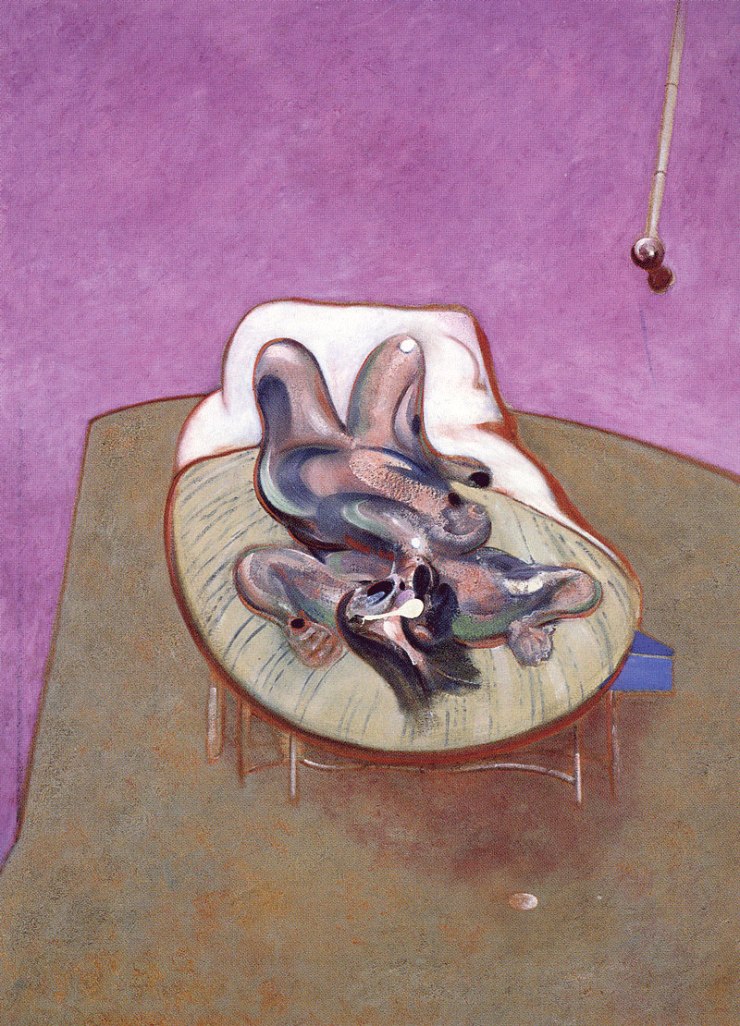

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon embraces fine art and modernism, while completely eschewing illustration. You can see fields of color in his backgrounds worthy of Mark Rothko, and abstract expressionist brushwork rivaling de Kooning in his subjects, but you will not see anything technically illustrated, or even drawn.

Andy Warhol

Warhol — technically a pop artist — melds commercial art with contemporary art, skipping fine art altogether, and barely touching on modernism or even illustration (his illustration work was of the loose, quirky, traced-over variety, and he did not possess the sorts of skills we might associate with someone like Andrew Loomis, who could, among other things, draw heads from any angle).

The reason Warhol skips modernism is because he appropriates both style and content, thus eliminating the originality of stylistic innovation that is inherent to modernism.

Barbara Kruger

Similar to Warhol, Kruger uses commercial art techniques for contemporary art purposes. It’s only her politics and provocative messages that separate her art from rather rudimentary commercial design. Traces of fine-art, modernism, and illustration are absent in her work.

Alex Grey

Alex Grey is a serious talent in the painting world who the official art world turns its nose up to, out of pure snobbery, both for his illustrational painting style and his psychedelic/spiritual/Buddhist content. His best works are serious fine art.

Mark Bradford

Hard as Mark Bradford and scores of others try to contextualize him as a contemporary, political activist artist, his work most resembles and succeeds as high modernist art. He has a great appreciation of abstract expressionist painting, and it shows in all his work, which obviously strives to reward the viewer with an aesthetic feast for the eyes. He doesn’t need politics to legitimize his work in the least, but for many, his status as a gay, black male, who uses materials from the black community (ex., fliers from his neighborhood, or materials from the beauty salon) is what makes him important. As urgent as his social agenda may be, it’s the pure visual power of his work on an abstract level that makes his best pieces shine, and that has very little to do with, and is often anathema to contemporary art proper.

Dana Shutz

Like Bacon, Dana Shutz falls between fine art and modernism. She is a figurative artist, but the way she renders her images has little or nothing to do with the way things actually look, while also referencing the history of visual art, including cubism, expressionism, abstract art, and abstract expressionism. Her art is only contemporary in the sense that she’s a woman working in the present.

Simon Stålenhag

As far as I’m aware the art world has not acknowledged any digital painter as a serious artist, and this may be because digital art lacks one-of-a-kind objects to purchase as investments, in which case, regardless of artistic accomplishment, the gallery system has no use for digital painting. Money, however, should not be our primary or any concern when it comes to how we assess or value visual art. Simon Stålenhag is an illustrator who works digitally, but whose sci-fi realist landscapes transcend the medium. Stålenhag’s digital paintings aren’t really art in the same way the Beatles’ songs aren’t really music, which is as seen through stupid prejudice and artificial hierarchies of high versus low art.

H.R. Giger

Similar to Stålenhag, Giger was an illustrator who used non-traditional means — in his case the air brush — to create unique imagery that transcends the limitations other people believe are inherent to the medium in question. Some might want to classify Giger as an illustrator, but does his work have more in common with Norman Rockwell, or Hieronymus Bosch? Because of the exceptional skill of his illustrations, the aesthetic beauty, his unique style, and most of all the extraordinary universe he created, populated by biomechanoids, Giger is a fine artist.

Robert Rauschenberg

Rauschenberg straddles modernism and contemporary art because he starts to use found objects like newspapers, a mattress, or a stuffed goat in his art, as well as imagery appropriated from popular culture. He maintains the aesthetics of abstract expressionism (think de Kooning), but integrates content such as social commentary.

Marcel Duchamp

Duchamp was not popular during modernism, but was resurrected when a connection could be drawn between his work and that of American mid-century artists such as Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, legitimizing the newer American art by giving it a longer historical lineage, and putting Duchamp on a pedestal as retroactively instigating conceptual art. Today, however, Duchamp is considered by many to have completely revolutionized art through his radical acts of exhibiting found objects as sculptures, most notably his urinal “The Fountain” of 1919. He is a “contemporary artist” in that he completely sidelines skill and originality, appropriates fully from everyday life, and is anti-modern, not to mention anti-art and anti-artist, before modernism was in full swing. His direct descendents include Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons, Martin Creed, Tracey Emin, and Maurizio Cattelan (some of who barely, if at all, add much to Duchamp’s century old stunt, ex., Creed’s crumpled piece of paper on a pedestal). Some have argued that Duchamp is a philosopher artist on par with da Vinci, but in reality they have nothing in common, don’t use the same medium, or speak the same artistic language.

Vincent Van Gogh

Van Gogh is a pivotal artist who embraces fine art proper, but looks forward to modernism. While his art remains figurative, his emotive stylization calls attention to the thickly applied paint itself, as perhaps never before, in which case his art becomes conspicuously about art itself, as well as whatever the subject is. As with modernism, his is an originator of a new style, and advances techniques of making imagery as well as what can be seen and digested as an image.

Caravaggio

Most the old masters are going to be fine artists, and using a lot of conventional illustration techniques. Contrary to much of what we hear in contemporary art theory, using representational drawing and painting skills to convey sophisticated content is a timeless avenue of creative endeavor, and is never behind some newer way of making art. To say otherwise is tantamount to asserting that memes replace literature.

LeRoy Neiman

Neiman made blanket illustration masquerading as fine art. His subjects, such as sports stars, never rise above the plebian, and his seemingly expressive brushwork expresses nothing other than a kind of cheesy flamboyance achieved with palette knife and gaudy colors.

Jeff Koons

Koons has presented himself as working in the tradition of Michelangelo (because of his plaster sculptures produced by hired artisans), and as improving the paintings of the old masters by affixing his trademark blue gazing ball to copies of old master paintings made by his assistants. He is not a fine artist, but a solid contemporary artist working in the traditional of Duchamp, here merely appropriating imagery and objects not from popular culture but from the museum, and recontextualizing them. His art does not use traditional skills, imagination, or aesthetics.

Carl Andre

Carl Andre and the other minimalists fall between modernism and contemporary art. They keep an object of aesthetic contemplation, and if it is extremely austere, that’s supposed to signal a more pure or elevated aesthetic experience. However, they reduce the element of the manipulation of medium to almost non-existence — there’s no virtuosity — and will use more common paints, or in Carl Andre’s case, floor tiles. While it’s a fallacy that your three year old can paint a Pollock, Twombly, or de Kooning painting, anyone can go to the hardware store, purchase the requisite number of tiles, and reproduce a Carl Andre sculpture. This places the idea of arranging tiles on the floor as sculpture, in the most simple arrangement possible, above any semblance of flair in the execution of the work. When the idea is as or more important than the execution, it’s safe to say we are in the realm of contemporary art practices.

Marina Abramović

Many an artist, including Abramović, are hybrid artists with one foot in conceptual art, and one in another media, in this case theater. Conceptual art + theater = performance art. Conceptual art + music = sound sculpture. Conceptual art + film = video. Oddly, all these hybrid art forms are classified as “visual art” and corralled with the tradition of painting and sculpture. In “The Artist is Present”, of 2010, Abramović sat across from whomever might join in the performance, for 8 hours a day, and 750 hours total. This is radical when compared to a painting that sits on a wall, but imagine if Meryl Streep had done this exact performance.

As theater it easily shades into cringeworthy self-aggrandizement. There are props, an actor of sorts, a stage area, it takes place in time, and there’s an audience, but we contextualize this not as closer to theater, but as inseparable from the tradition of painting. Hybrid art forms tend to have far more in common with genres outside of visual art, but are nevertheless contextualized and shown as the latest development in the traditional of visual art. This is why video is not contemporary film, performance is not contemporary theater, and sound sculpture is not contemporary music, but they are all contemporary art. Only visual art proper is excluded from contemporary visual art. Thus, anything that doesn’t resemble visual art is surely contemporary art, and the presumed exalted apotheosis of visual art.

Andy Goldsworthy

Goldsworthy is the gateway artist for contemporary art, because it’s really, really hard to not like his work. His art is contemporary because he uses found objects (from nature, as it were), and makes ephemeral compositions. True, they are aesthetically beautiful, in which case they harken back to modern art, but there’s no traditional skill necessary, and most of his oeuvre consists of outdoor installations of a sort, in the woods. If someone says they hate contemporary art, have them look at Goldsworthy, and it they don’t change their mind, it might be their personal problem.

High versus Low Art

People assume that contemporary art is high art and illustration is low art, but as in the examples I gave above, there are outstanding exceptions where the art transcends the supposed limitations of the medium. Some contemporary art is threadbare, and a few of the examples I gave are not anything that I admire (works by Levine, Boyce, and Cattelan).

Rockwell’s The Problem We All Live With, of 1964, is an outstanding example of an artist we associate with cloying nostalgia and facile technique rising above the occasion to make a true masterpiece of fine art. His compositional use of the titled bright yellow armbands of the US Marshalls, and the splat of the tomato reference abstract and abstract expressionist painting. There is an amazing use of shallow space, creating a stage (note the thick line in the wall that bisects the painting), and this has to be one of the best uses of fists — and even contrasted with shoes — in all of painting. The audience is placed in the vantage point of the people who would taunt and throw food at the girl. Notice you can feel the wooden ruler in the her hand. I could go on and on. The point is that an artist synonymous with cliches, working in a style primarily used to sell products, is capable of using that same medium to address the human condition, a historical event, and all integrated into a stunning visual buffet. If nothing else, the painting is an outstanding aesthetic achievement.

On the other end of the spectrum, Martin Creed’s contemporary sculpture, Work No. 294 — and one in a series of crumpled A5 pieces of paper — is utterly vapid, and ads precisely nothing to Duchamp’s stunt of exhibiting found objects starting as far back as 1919. He fails where Goldsworthy succeeds magnificently, while both artists’ styles revolve around arranging found or modestly altered objects. Goldsworthy surprises us with the beauty of natural objects, and Creed rubs our noses in mundanity, as if Duchamp and Koons hadn’t already done that in spades.

Regardless of style, medium, discipline, or however we may want to categorize or contextualize art, it is always the case that the best art transcends the vehicle used. In short, it’s never the medium that matters, and always what one does (or doesn’t do) with it. Nevertheless, individuals will gravitate to certain kinds of art rather than others, and this is as it should be, otherwise we’d only have one kind of art.

~ Ends

Incidentally, My childhood foundation is illustration; in community college I learned fine art; as an undergrad at UCLA the focus was on modern and contemporary art; and my graduate education at UCI was in radical conceptual/political art. Nowadays I make digital art, mostly digital painting, and am moving more towards illustration, with a solid footing in fine art, and hints of modernism and contemporary art.

And if you like my art or criticism, please consider chipping in so I can keep working until I drop. Through Patreon, you can give $1 (or more) per month to help keep me going (y’know, so I don’t have to put art on the back-burner while I slog away at a full-time job). See how it works here.

Or go directly to my account.

Or you can make a one time donation to help me keep on making art and blogging (and restore my faith in humanity simultaneously).

Outstanding article!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for this, I’ve often been confused between the differences, especially between modern art and contemporary, but then you go so much deeper, clearly, I have so much more to learn! I always look forward to your posts!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Hi Tiffany. We often use modern and contemporary interchangeably, but contemporary art is much more associated with postmodernism, and can even be quite anti-modern, such as in its rejection of originality. When I was in grad school, which was entirely radical conceptual art, an artist would have been scorned and ridiculed if her or she tried to make modern art (or fine art, or illustration).

Thanks for commenting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lots to think about here. Thanks. I’ve tried to categorize art, too, tried to understand how works by Duchamp and Koons are in the same category as Michelangelo and van Gogh. They all have so little in common. Your breakdown helps: Michelangelo was an illustrator, van Gogh a fine artist, Duchamp was modernist and Koons is contempt-orary, yes?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Howard:

I edited the article to include Duchamp and Van Gogh (as well as Robert Rauschenberg).

Duchamp and Koons are definitely not in the same category as Michelangelo and Van Gogh, no matter what the most esteemed art critics of today might say, especially because they don’t even make their own work, in which case there’s no skill, aesthetics, or imagination involved. They both belong to contemporary art practice, and Duchamp is the father of it. They both deny originality, appropriate everyday objects, and are anti-art. Most contemporary art regards Duchamp as the genesis of their genre.

Van Gogh is fine art with modernism. He works semi-realistically, but is definitely an originator and contributes to the evolution of the science of art, so to speak. His emphasis on brush strokes and the surface of the painting was audacious for the time, and his mere application of impasto paint is an acknowledgment of pigment as the subject of art in addition to whatever he was painting. His art is highly about art itself, which is a core characteristic of modernism: art for art sake, and art about art.

I’d say Michelangelo is a fine artist – consider his statue of David – but has the skills of an illustrator down. Like some illustrators of today, he transcends the limitations of the medium in terms of quality of execution and depth of content, especially since he was living long before there were cameras, and thus illustration served broader purposes, including being the only possible depiction of visual reality. For me, the difference between fine art and illustration is a lot like that between literature and genre fiction: both may use the same grammar and share the form of the novel, but one attempts to deal with the human predicament while the other one largely seeks to entertain. Illustration is usually a means to an end (ex., advertising a product), but fine art is an end in itself.

Thanks for reading and commenting!

LikeLike

I think it should be pointed out that Koons did not recreate that Manet painting. He had his assistants do it, like all of his work. He’s just the idea man.

Excellent article! Great examples, and thank you for introducing me to new artists.

LikeLiked by 2 people

…lets see if I can the obvious but well-done satire on JK…. oh dear. Sigh. I genuinely thought it was a parody (the resin-balloon doggy with accompanying poop-gift.) Now I don’t even know if he has a copyright on the thing or not – which is itself rather indicative. An aspect, only slightly distinctive (in your article a confluence with politics, and in a way illustration – inherently,) I think: social commentary. Which, well… is nearly always limited. No, always – if it’s the only or primary element of the work.

LikeLiked by 2 people

…ah, forgot – great article.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This breakdown and description of types, movements and example artists is helpful and stimulating. Thank you for writing it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I do what I can hither and thither. Cheers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So interesting!!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks. Glad you liked it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very informative article, but I question in the Breakdown section ranking Contemporary art having no imagination or originality. It’s often said about contemporary art “I could have done that” or “any one could do that”. The same was said to Johan Vaaler. A contemporary artist has as much as or in some cases more imagination than a Fine art artist, whose work is often formulaic

LikeLike

Very informative article, but I question in the Breakdown section ranking Contemporary art having no imagination or originality. It’s often said about contemporary art “I could have done that” or “any one could do that”. The same was said to Johan Vaaler. A contemporary artist has as much as or in some cases more imagination than a Fine art artist, whose work is often formulaic

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for reading and commenting. And your point is well taken. It does sound hard to deny the imagination and originality in a genre, unless, of course, I am talking about the further end of the spectrum, which seeks to be neither. If you want a radical departure from modernism, you go in the opposite direction.

Look into the theory, such as Rosalind Krauss, who is a mastermind behind contemporary art. They don’t believe in originality, hence the postmodern heavy reliance on appropriation. This goes all the way back to Duchamp. As I said, they can acknowledge being clever, and innovative, but not original, according to their own underlying philosophical underpinnings. This is a tradition coming out of “anti-art” which is also “anti-artist”. I also emphasized that I am talking about in relation to the other genres, and postmodern art is reacting against modern art, and very strongly against its notion of originality.

Ask yourself if Sherry Levine re-photographing Walker Evans photographs is original. It’s not meant to be. It’s a comment on the death of originality, and, mind you, these guys all fawn over Roland Barthes’, “The Death of the Author”. You ain’t contemporary if you don’t think the author and originality are moribund. I’m not being mean when I say it’s not original. I’m just acknowledging their own take on themselves.

On the other hand, I agree with you that some of it has got to be original and imaginative in spite of the overarching theory.

Thanks for reading and commenting.

LikeLike

Thanks for this helpful taxonomy.

I have become interested in Western art, which as far as I can tell from your article is basically illustration, perhaps shading in to fine art, but springing out of love for a particular region, landscape, and history.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Well, before the 20th century most art was going to be representational, but it’s kinda’ like my analogy of literature versus genre fiction (ex., romance or sci-fi), in that the old masters addressed more serious themes and did so with greater skill than illustrators in general, but there’s far more overlap in the past between the two.

LikeLiked by 1 person

But Western art is still a thing nowadays.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is kinda’ funny because I’m not sure if you mean “Western” as in European-derived, or “Western” like a Western movie. But, both exist, and that’s a very good thing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ooops, sorry. My face is red. 🙂

I meant Western art in the narrow sense: coming out of the American West. Landscapes features rocky mountains, deserts, mesas, and cacti; paintings of cowboys and of pinto horses standing in the snow, etc.

My grandmother was a painter of all that stuff. She used to get these magazines dedicated to what they called “Western art,” and they included everything from plein-air painting events to jewelry and pottery to art shows. I never knew until I saw those that there is a whole, vast subculture of “Western” artists making and selling their work. The subgenre (if that’s the word?) seems to me like a sort of refuge for representational, usually illustration-style art. Then recently, I moved to the West and fell in love with it myself. You fall in love with the landscape, and you want to paint it.

If I had meant Western in the sense of European culture, that would have been extremely broad and would have cross-cut all the categories you laid out in this post.

Sorry I don’t have the vocabulary to talk about this stuff that you do. I feel like I’m digging a deeper hole with each clarifying comment that I leave. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nope, that was very clear and well put. Nothing wrong with more regional art, and falling in love with landscapes. Sure, you’d never be allowed to do any of that in the art schools I went to, but I personally have always fantasized about learning to do plein-air landscape painting, in oils, with the easel and palette and all that. Not only would I have enjoyed that infinitely more than my radical, conceptual, political art education, I’d have been able to make a career at it if I wanted to.

But, I’m also happy with the dark, sci-fi, psychedelic, spiritual digital paintings I’m working on.

One day I’ll take a landscape oil painting class tho, I hope. Probably not in the cement and asphalt city I live in right now in Thailand, though.

LikeLiked by 1 person

P.S. The picture by Dana Schutz looks to me exactly like the self-portraits in your post about Suzzan Blac.

LikeLiked by 2 people

There might be some overlap, but if you look at enough works by both, Shutz is a lot more whacky and even cheerful as compared to Blac. But I think I see what you are getting at.

Thanks for reading and commenting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Delightfully, comprehensively illustrated (no pun intended). I also appreciated the chart comparing the four different categories of art and what they did or did not have in common.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Glad you liked it. I thought it was useful, and, oddly, I haven’t seen anything quite like it.

LikeLike

As usual, so gratifying to have so much to chew, Eric. Like Tiffany in her comment before, I’ve been confused enough about what each “art” is I gave up on it, lol! This helps, and in a very good way, at least for me, as I get more and more the general thrust of many of your posts.

Your Norman Rockwell exploration/commentary was superb! And I think your statement, “… it is always the case that the best art transcends the vehicle used” is – for me – amazingly encouraging!

Thank you! 😊

LikeLiked by 2 people

That’s great! And you picked the kernel of wisdom out of the whole post. Whatever piece really succeeds does so because it transcends the medium, no matter medium.

Thanks for reading and commenting!

Eric

LikeLiked by 2 people

You bet, Eric! I really appreciate the thought and time you put into these, they’re invaluable, and interesting, a rare combo 😊

LikeLiked by 2 people

Excellent.

LikeLiked by 2 people

10ks for sharing!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes!!! I’m gunna learn a lot from you. Your style of writing and blog posting suits me 🤓 down to a 🍵

LikeLiked by 2 people

Cheers for this, excellent read. Doesn’t take me any closer to seeing where I sit, but such is life. I was wondering where you would put Anselm Kiefer, who to me seems to sit in Fine Art, Modernism and Contemporary under your classifications (and yes, I understand that nothing can be rigid in defining art 🙂 )

LikeLiked by 2 people

Well, Anselm Kiefer is among my very favorite living artists, and I’d say he’s pretty strongly between Fine art and Modern art. As I said in the article, my table indicates more what is minimally necessary to qualify in a category, not what is maximally possible. So, for example, fine art can address politics, but it’s not a standard feature of it.

Kiefer uses a lot of aesthetics, and references the history of fine art painting and sculpture. He makes historical landscapes, which is not at all out of step with fine art. The grand scale and the materials shade into modernism.

Despite the politics, I don’t consider him “contemporary art” because of what his politics are. It’s not identity politics or social justice: it’s history. His art always seems focused on the past.

His art is also based a lot on feeling, sensation, and tries to create an aura of sorts suggesting a long and rich history. He also frequently teeters on Expressionism.

Most artists that make paintings that look good are going to be fine artists. However, we tend to classify non-white male artists who do work around identity politics as contemporary in order to promote their work in an anti-fine-art-painting era. In reality, they are also fine artists, IMO.

Just looked at your work. Solid fine art. I see why you like Kiefer, too.

Thanks for reading and commenting.

LikeLiked by 2 people

very interesting. This is the first time I have heard the styles described as precisely as this. I truly never thought about it this much but your examples really hit home. Nice stuff Keep Smiling

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hadn’t seen it broken down like that either, and I thought it would be a good basic tool for people learning about art. That’s why I made it. Thanks for reading and commenting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting and well put together. I was able to follow along and not get confused

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad to hear that. I hope I can make things clear and help people undestand them a little better.

Thanks for reading and commenting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey! Great read! Do you think you could help me categorize what my art leans most towards? https://alwayscomealive.wordpress.com/my-art/

LikeLike

Hi Veronica:

I think your art falls into traditional fine art.

LikeLike

Traditional Fine Art, wonderful thanks so much for your help Eric! I’ve always had trouble answering people when they asked me “what kind” of art I paint.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such an educational post that really explains the different types of art. Awesome work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! Gland you found it useful.

LikeLike

Your articles are very insightful.

I never knew anything about Goldsworthy. That work looks very appealing and it has some idea as well as in contrasts and subjects.

I’ve basically become an introvert. I used to read a lot about art history and also followed the art world events, but that was some 30-40 years ago. One sort of loses interest when it’s all the same: contemporary is great, traditional is bad.

I suppose, you’re located in LA and that also makes a difference.

In Canada, there are only 3 types of art which get attention: photorealism, abstract art and contemporary whatever it is: installation or something on a flat surface. That’s it. All the other artists sort of boil in their own juice. I have a few friends in SF, they paint abstract art mostly. I don’t think they are famous, but that art is worth looking at. I’ve been only once in SF, and we drove by LA, never stopped there because my husband cannot stand places like that. I would have loved to at least see how it is really over there, but that probably won’t happen that soon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you like Goldsworthy.

Incidentally, I’ve been in Asia for the last 15 years, between China, Thailand, Vietnam, and Cambodia. I was, however, born in LA, and also lived in NY for 8 years. I have no idea where I’ll be 5 years from now. And I would never had predicted I’d live in Asia 20 years ago.

Like you, I lost interest in the art world for the better part of 20 years. There just wasn’t really anything that I was aware of that really captivated me and made me want to be a part of it. That and I had my workaday jobs.

Thanks for reading and commenting!

LikeLike

Yours is a solid taxonomy that helps the art enthusiast grasp the greater “discipline”. I will be forever grateful for the your reference to Andy Goldworthy – I fell in love with his work, immediately.

That said, I find your summary statement about Fine Art a bit perplexing – you say “This style is not taken as seriously in the art world anymore, is considered backwards or craft, and it’s difficult to make money at it.” This statement is too dismissive. There seem to be far too many examples of thriving museums, galleries, auctions houses, art publications, etc. that emphasize or at least devote a portion their “space” to “fine art”, as you have defined it, to say that it is not taken seriously… Sure it’s “hard” to make money at it, but I’d argue that it’s “hard” to to make money at art, period.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, you took me a bit literally there. My point is that contemporary fine art isn’t taken seriously, as compared to contemporary conceptual art…

LikeLike