I watched a mini-documentary “Beauty: Explained” on Netflix, and a few pieces fell into place regarding how art is considered today. Before I connect the dots and introduce what the new science suggests, I will need to review what the dots are, and what they signify. If you already know your contemporary art history, you can scroll down to Part 2.

Part 1

WE ARE TOLD ART IS ABOUT IDEAS

If you are familiar with contemporary art discourse, you know a very popular theme is that the purpose of art is to ask questions, start conversations, and challenge previous notions of what art is. This tradition goes back to Duchamp, who tried to exhibit a urinal in an art exhibition as a challenge to popular fine art, such as the Impressionists, who he believed were “too retinal”. Art needed to be about ideas, to be critical, and not just be pretty fluff to gaze upon while daydreaming. “The Fountain”, as he cleverly named his urinal, did not need to be seen, according to the artist. Only the idea needed to be considered.

Some may think that we were supposed to admire the inherent beauty of the mass-produced object, which in some senses individually hand-crafted objects couldn’t compete. However plausible that may seem — and it’s what I used to think as well — it is not Duchamp’s stated purpose.

He wanted to present something that had zero aesthetic interest, neither attractive nor unpleasant, but towards which one would have sheer indifference.

“There’s no style there, and no taste, and no liking, and no disliking either”.~ Marcel Duchamp.

This was, after all, anti-art.

Duchamp wanted to do away with visual art, and replace it with a more conceptual, idea-based art. His eventual exhibitions of things like a snow shovel, a bottle rack, or a comb were intended to neutralize prior art: if his art was in the gallery or museum, and there was no element of aesthetics or skill, than all skill and aesthetics are extraneous to art, and art if a farce. Indeed, his parodies attacking visual art are now held as the highest achievements of visual art. He has even been held up as the da Vinci or our era:

“Fountain was many things, apart, obviously, from a mis-described piece of sanitary equipment. It was unexpectedly a rather beautiful object in its own right and a blindingly brilliant logical move, check-mating all conventional ideas about art. But it was also a highly successful practical joke.

Duchamp has been compared to Leonardo da Vinci, as a profound philosopher-artist…” ~ Martin Gayford, for The Telegraph.

This trend continued and can be seen, or rather not seen at all, in invisible works by Yves Klein [who exhibited empty space] or Robert Barry, who released invisible helium in the air as art.

About this piece, art critic, David Joselit wrote:

It challenges our definitions of an object. What kind of thing is a cloud of gas dispersing into space?

Artists and critics came to believe that art is ultimately a form of linguistics. Joseph Kosuth articulated this well:

The propositions of art are not factual, but linguistic in character – that is, they do not describe the behavior of physical, or even mental objects; they express definitions of art, or the formal consequences of definitions of art. ~ Joseph Kosuth.

Art here is seen as making propositions, and those are necessarily “linguistic in character”. This understanding is fundamental to postmodernist and related philosophy, which maintains that there is no meaning outside of linguistics. Everything we understand is in the context of our belief systems, and all belief systems are woven in language. Everything is understood only through linguistic structures. Outside of linguistics, there are certainly things, but they are without context or meaning. Art critics love this stuff, as it privileges language [their specialty] over images [the traditional core of art], and so do the more conceptually bent variety of artists. You can see outstanding examples of this viewpoint in works by Lawrence Weiner.

Me, I never bought into any of this. I read a book on Zen when I was 18, and so was already well familiar with the polar opposite notion, which is that linguistics creates a fiction, and the way to know reality is to relax the mind and allow the tyranny of linguistic thought to dissolve. Only by escaping linguistics could one bask in the light of unvarnished reality. And I knew that I didn’t enjoy my favorite art on a purely cerebral level, and in sentence structures. Some of my richer experiences of art were just marveling at brush strokes and colors in reproductions of paintings in books.

I could just look to music. When listening to music, I most enjoyed it when I wasn’t thinking about what it was, or making sentences in my mind at all. I don’t know about you, but when I think I imagine the sound of my voice articulating the words. So, for example, when I meditate, I don’t like to count my breaths because I can feel a tension in my throat and as I voicelessly articulate the numbers. I can’t really relax my breathing if I’m counting in my head. And so it is with music. When I was in high school I used to have to rewind my tape casettes while listening to music in the dark with headphones at night, because I’d been thinking through a passage I wanted to listen to, and thus didn’t hear it. The point is, you can’t really listen to music while talking in your head. I couldn’t reconcile the idea that music must necessarily be 100% linguistic while being impossible to really enjoy unless one sidelined linguistic thought. And if music wasn’t about linguistics, than why did visual art have to be. Visual art doesn’t even take place in time like music, in which case the parallel is harder to make between a still image and concepts unfolding in time.

In sports as well, as long as I can remember, if I really wanted to perform well, I had to stop thinking about whatever. I use this technique today when I need to swat mosquitoes. I stop thinking and just wait. I don’t think “NOW!” I just do it when the time is right. I rather think this is a big part of why people enjoy sports: they get to get out of their minds and mental loops. You can’t really think about what you are doing while playing sports because you can’t think fast enough. Of course the pitcher will consider which kind of pitch he’s going to make — fast ball, curve ball, slider, knuckle ball — but that’s between moments of action. If the batter hits a line drive back at his head, the pitcher doesn’t think, “I’d better catch that ball with my glove or I’ll get knocked out”. He’d have been knocked out before he got to the word “catch”.

I’ve argued many times that visual language is not the same as linguistic language, or “text”. Neither, of course, is music. This is why I can thoroughly enjoy music where I can’t understand a word.

I’ve never been to Tanzania, don’t speak Swahili, and according to a lot of contemporary sociopolitical theory, I surely can’t understand what it means to be a black man in Tanzania. Nevertheless, I love the music of Hukwe Zawose, and bought two of his CDs more than a decade ago. I don’t care about the idea of what the music is, and I don’t know what it is literally about, yet it speaks to me in some other way. It is a kind of intelligent communication outside of linguistics.

I love the paintings of machine orbs by Masakatsu Sashie.

I don’t need to speak Japanese to enjoy them, or understand them. I don’t need to speak at all.

CONCEPTUAL ART REPLACES VISUAL ART AND RENDERS IT REDUNDANT

The second dot is this notion about the evolution of art and artists. Some people who weren’t exposed to this belief don’t really think it’s a thing, or think I’m exaggerating, or point to instances of paintings in galleries, and so on. I wonder if they went to art school, when, and where. I went to UCLA and UCI in the early 90’s. Not only painting, but aesthetics in general were considered antiquated, irrelevant, busy work, and mere frills. I think Chris Burden expressed this view very memorably.

if some of the people at the turn of the century were here now they wouldn’t be making paintings, they’d be doing art like I’m doing, or some people I respect are doing. Do you know what I’m saying? But people want to see that same format continue, which I don’t think is really very realistic, because the people that we respect in art history were… at their time seemed difficult, and outrageous, and pushing something, and that is basically the history of art, y’know, is that it does push your head around a little. ~ Chris Burden.

Here he is talking about it, if you’d like a live version:

I signed up for Chris’ “New Genre” class at UCLA, but for reasons I didn’t find out about until much later, I got Paul McCarthy instead, who held the same views. Notice here that it is not realistic for the format of painting to continue. This is what I was told when I was a student who wanted to be a painter. And also notice that it is not only not realistic, artists who make paintings are not respected. When he says that real art is supposed to push your head around a little, he means the new concepts are what really matters in art.

Art critic for the Guardian, Jonathan Jones, expressed the same sentiment thusly:

Let that sink in. I made that graphic, but couldn’t squeeze in the whole quote. There’s more to it. Behold the brilliance:

There is a profound difference between art rooted in craft, and art that has no interest in it. In this century, art has left craft far behind. A process that began when Marcel Duchamp insisted art should appeal only to the brain is, today, complete. Painters who know how to paint are relics from another world and sculpture no longer seems the right word for the objects artists find or cause to be made. ~ Jonathan Jones, Mar 30, 2009.

Wait, there’s more evidence that this is a real thing. Here’s another graphic I made for a quote by Joseph Kosuth:

Here, painting isn’t even art anymore, because when you make a painting you aren’t even questioning what art is, and the real purpose of art is to question what art is. Painters are not artists!

My New Genre teacher, Paul McCarthy, believed he eclipsed the tradition of painting and burst out of the bubble of it’s limited scope:

In his early works, McCarthy sought to break the limitations of painting by using the body as a paintbrush or even canvas; later, he incorporated bodily fluids or food as substitutes into his works. In a 1974 video, Sauce, he painted with his head and face, smearing his body with paint and then with ketchup, mayonnaise or raw meat and, in one case, feces. ~ Wikipedia

You can see for yourself what it looks like when you transcend the entire history of western painting:

Honestly, I find this video extremely boring, cringe-worthy, and obviously disgusting, but that’s not the point I want to make here. McCarthy thinks he’s gone beyond painting without knowing how to paint at all. The musical equivalent, and I’m not exaggerating in the slightest, would be to convince yourself and the public that you are going beyond Beethoven’s piano sonatas by slathering condiments and crap on a keyboard and rubbing your ball-sack back and forth over the keys.

Do you believe me now? Here we have it, Duchamp’s revolution has fully succeeded in thoroughly sidelining painting. If you can paint you are yourself a relic! Painting well is mere craft. The format is obsolete. And painting with condiments and shit constitutes leveling up your game from the whole tradition of visual art [you may have noticed that Jones asserted that even “sculpture” is no longer an adequate term for objects artists make].

What art is about is IDEAS! Also notice the Jones quote is from 2009, and I was being drilled in these conclusions as early at 1990. That’s a span of a decade, but this view had been around since the late 60’s — Robert Barry’s invisible gas art is from ’69 — and persists today. Whole generations of artists were shot down if they wanted to make visual art proper, and steered in other directions, including me.

Not to be extinguished because fo my chosen medium, I did performance art, photography, and installation at UCLA, and received a $10,000 fellowship in my senior year, which was awarded to just one student. You could say I beat them at their own game, but was ultimately defeated anyway because I didn’t get to make the art I wanted to make. Instead, I simply worked in other mediums, which to me was then and now about the same as switching from painting to writing short stories or composing music. I was still being creative, just using different tools that were initially alien to me. I thought it was good training, and I also bought into a lot of the rhetoric of the time. I didn’t get a 4.0 in Contemporary Art Theory just because I was THAT clever. I believed in it!

Only later, when I got out of the environment — much like one leaves a cult — did the pieces eventually settle in a more sane and integrated perspective. Contrary to the grandiose attestations of Burden, Kosuth, McCarthy, and the rest, conceptual art did not evolve out of visual art and replace it. It has nothing to do with it. It is a different medium altogether, and replaces visual art as much or as little as it replaces music, literature, theater, and dance.

What we end up with is artists who use one medium declaring that they are superior to artists who use an entirely different medium. They will deny that with delusional arguments about how their installations, which may happen to splatter a bit of paint or ketchup are all-encompassing and integrate painting within them. Another of my professors, this one from UCI, made this sort of argument. Here he is in an interview:

I think that we often feel that in mixed company, or in a context where I would suggest instead of using mediums of art-making, let’s talk about language. So, in a context of multi-linguality — so, if I’m in a space where the majority of the people in the room speak four or five different languages and move very easily among those languages without a thought, and then you have one person in the room who only speaks English, that person starts to feel very uncomfortable because of not being able to enter into those discourses easily because they lack the tool of the language. ~ Daniel Martinez.

Here he’s using being multi-lingual as an analogy for using a variety of physical mediums, or aspects of artistic traditions, in an installation and/or performance piece. He flatters himself that he can move between these disciplines, including painting, without a thought. The painter, however, can only speak one language, and is thus critically limited, a crashing bore, and the pariah of the party. He can only speak one language.

I don’t know how many languages Martinez can speak, but I can speak 5 – English, French, Chinese, Khmer, and Thai. The analogy doesn’t work. I know first hand that my elementary skills in foreign languages don’t allow sophisticated conversations at all. I’m limited to greetings, directions, buying things, and practical stuff. If Martinez’s painting skills were adeptness at a language, he would only be able to articulate a few stock phrases before resorting to grunting and gestures. The problem with his analogy is that he doesn’t move very easily among artistic disciplines without a thought. It’s claiming fluency when one is really struggling to say anything at all. In short, Martinez can’t paint! And neither can McCarthy, or Burden, or Weiner, or Kosuth, or Jones for that matter.

Even Marcel Duchamp himself, and despite some promising early paintings, admitted he didn’t have anything to say in painting:

“I didn’t have any ideas to express. I didn’t, never, considered myself like a professional painter. You know, a professional painter is a man who paints every morning. And he paints quickly or slowly, but he paints all the time. And painting always bored me. Imagine. So, I had a hard time finishing a painting.” ~ Marcel Duchamp

It’s true that Paul McCarthy went on to make paintings that look like Jonathan Meese on a particularly trying day. You be the judge:

I suspect McCarthy thinks blatantly unskilled painting is a superior sort of painting: it’s good because it’s bad. This is a painting, but not only is there no evidence of any conventional skills, unlike a de Kooning, it’s not even aesthetically interesting or appealing. Here’s the work of a multi-millionaire artist, with all the free time and any resources he needs to make a painting, and this is what he comes up with. In the center is someone fisting a woman, and at the bottom there’s a lot of shit-colored pigment [that’s deliberate, and a bonus, folks], particularly the more green-brown slab at the bottom. And is that thing between the standing figure’s head and the messy stuff on the right with photos on top (a direct rip-off of Meese) Santa Claus? The underlying notion is that because McCarthy is so brilliant about art in general, surely he can use those skills to make paintings as well, especially when craft and aesthetics are the artistic equivalent of extinct species, beat out in the survival of the fittest. The end result is an assaultive, pornographic grotesquerie, that is probably intended to offend. Sometimes, in less forgiving moments, McCarthy’s entire career seems to me to revolve around the logical fallacy that if great art shocks and offends, offensive and shocking art is great [If all spotting dogs bark, all barking dogs are spotted?!]. I digress.

Here we have a bunch of people who suck at painting, to the degree they can do it at all, smugly declaring they have mastered it, are beyond it, and have transcended it. They have no more transcended painting than they have the great American novel. They haven’t even scratched the surface.

The way this works for them psychologically is that they can look to the abstract expressionists, or minimalist painters, and they can see that they too can fling, drip, spill, splatter, or roll on paint, in which case they can credit themselves — presuming they understand the underlying philosophical ideas — with knowing how to paint. Painting is reduced to just applying pigment to a flat surface, and that’s it. This is how Paul McCarthy can conclude that he’s going beyond the limitations of painting by smearing condiments and feces over his body: painting, in his mind, culminated in smearing pigment on a flat surface, whereas he’s smearing it outside of the rectangle. This is what happens when people come to understand art not through looking, but through texts and the dialogue surrounding art. If you reduce visual art to props illustrating various ideas [ex., pointillism is about primary colors blending from a distance…], than why not just make props directly to illustrate ideas? While I’m still learning to paint [digitally, these days], people with far less skill, practice, or appreciation of painting blithely declare themselves as having mastered it, or rather the “discourse” surrounding painting, and particularly the one that disregards it. In the end, what constitutes fluency in painting is merely familiarity with ideas that disregard it coupled with an ability to make any mark on any surface.

And all it takes to get the ideas is to read the appropriate articles. Thus, anyone can master painting without being able to paint a paper bag, draw and shade an egg, or do a portrait that isn’t an abomination, and so on. They definitely can’t paint something passably realistic from their imaginations (in which case you really need to understand the principles). They have convinced themselves that none of that is necessary, or relevant. Game Over! This is akin to calling yourself a musician if you can make any sound at all, record it (with your smartphone), and play it back.

In reality they are artists working in one medium blithely disqualifying artists who work in another medium. All of them would have to admit that compared to, say, Low Brow legend on the other end of the artistic spectrum, Robert Williams, they didn’t have any of the skills necessary to produce one of his paintings. Whether you like William’s style of painting or not, it’s quite a stance to pronounce oneself beyond something one can’t even begin to do oneself.

And, no, incidentally, I don’t do the same thing to them. I’m a fan of a lot of Burden’s art, and can appreciate some of McCarthy’s productions as well. It’s their rhetoric that attacks visual art proper that I am against. I’m all for artists making any and every kind of art they want to. I’m sure, because they were my teachers, that McCarthy and Martinez struggled when getting new students whose entire concept of art was just drawing and painting, and who only wanted to do drawing and painting. I can understand the frustration. But just because some people who want to paint images are only familiar with or capable of that, doesn’t mean everyone who wants to do so is similarly hampered. Just because your medium is visual communication, using visual intelligence, visual language, and the imagination, doesn’t mean at all that you are hopelessly lost as compared to someone who uses a hodge-podge of other tools.

It’s not the medium you use, just as it’s not the language(s) you speak, but rather what you say or do with it that matters.

Part 2

TURNS OUT ART ISN’T ABOUT IDEAS

Some art, such as the pieces I shared by Robert Barry or Lawrence Weiner, certainly are about ideas, but that does not, as their pronouncements insist, extend to all or most other art. That is more of a fringe category of art, which merely presupposes that it reigns supreme over the entirety of creative, artistic enterprises. Mind you, there’s nothing wrong with making idea-based art, and I definitely prefer to live in a world with even the more threadbare conceptual pieces in it [though I will NOT sit through a McCarthy video!). And I do consider Burden’s “Shoot”, in which he had himself short in the arm by a sharpshooter, as art, to be art.

But this is only one kind of art, and its rhetoric only really applies to itself. It’s time to stop declaring that art that doesn’t question what art is isn’t art, as Joseph Kosuth has, and instead make less sweeping and tyrannical claims, such as, “My art questions what can be considered art”.

And here comes the science. While beauty has been disregarded as irrelevant or even detrimental to contemporary art, it nevertheless does have a direct impact on the brain, connecting areas of pleasure [three neurotransmitter systems: the dopamine, the endocannibanoid, and the opioid] to the visual cortex:

Our view is that the combined activation of the visual cortex and these rewards systems together is the biologic response to beauty. ~ Anjan Chatterjee (neuroscientist)

OK, for starters, when we remove beauty from art, as Duchamp has so infamously done, this sort of pleasure is not going to occur in reaction to the art in question. People may be perfectly fine with that, and consider the more austere variety of art that includes no visual pleasure to be superior, as its ideas are much more important, and there may certainly be some other kind of pleasure involved anyway. They might also argue that political art has a much more important mission than merely stimulating the same pleasure centers as opioids, but through a visual avenue.

When researchers studied the brain during instances of peak aesthetic experience, they discovered that the DMN [or Default Mode Network] of the brain lights up. The DMN is, according to Chatterjee, like an “idling state of the brain”. Significantly, this part of the brain dims when someone is asked to perform a task, or to think about something specific, but lights up when we aren’t performing a specific task.

The Default Mode Network is activated when our minds turn inward.

They probably reflect a kind of internal state, when you’re kind of spacing out, when your mind’s wandering, when you’re self-reflective. ~ Anjan Chatterjee

When test subjects were shown paintings that most appealed to them, that’s when the DMN came into play.

It is triggering a whole set of associations and thoughts in our own brain, which is a kind of free play of our own imagination. ~ Anjan Chatterjee

The researchers see this as proof that, in the words of the narrator, “our experience of beauty involves connecting our senses and emotions with something personal. Our sense of self.”

There’s something about being moved by paintings that forces us to be self-reflective. That may be the biologic signature of what it means to feel moved by a painting. ~ Anjan Chatterjee

Here, we learn that aesthetic appreciation causes specific areas of the brain to engage, and corresponds with an internal, self-reflective state that allows a free play of associations within the imagination, all intimately related to our inner selves. That’s got quite a lot going for it beyond just the dopamine, opioid, and cannibanoid hit. It is not, as Duchamp denounced Impressionist painting, merely “retinal”. It is also at cross-purposes with thinking about something specific, which conceptual art strives to do, and within the terrain of linguistics.

This is not to say that art which revolves around ideas in linguistics, shuns aesthetics, or reviles beauty, is not art, or is not as good of art. What it does show is that visual art proper (and here painting in particular):

- provides a unique kind of pleasure

- uses a different part of the brain

- arouses a different mental state

- engages the imagination

- sparks self-contemplation

We don’t get that from the urinal, Shoot, invisible art, or a sign imploring use to learn to read art. Those works may do something else, and there may be some overlap, but if we were to believe Chris Burden, Joseph Kosuth, or Jonathan Jones that painting is washed up and irrelevant, we’d lose a whole avenue of rich human cognition and communication. According to science, it appears that their own work doesn’t even operate on the centers of the brain associated with art, or the pleasure of looking at it at all.

Visual art is its own language, operates outside of linguistics, and is only related to conceptual art in terms of chronology, not inherent traits or capacities. One art form does not, and can not replace another. Further, conceptual art and its hybrids do not remotely encompass visual art or visual language (especially when they use it minimally, and incidentally, if at all) any more than they envelope music or literature (just because they incorporate sound or text).

The people who maintain that painting and visual art are somehow redundant or beneath any other art form are themselves “relics of a another world”. If they still insist visual art has no purpose today, and they don’t want those pesky parts of their brain illuminating, or to undergo that kind of self-reverie, I think they might still be able to, in some places, and for the right sum, get that lobotomy that will finally truly make painting meaningless in their lives.

~ Ends

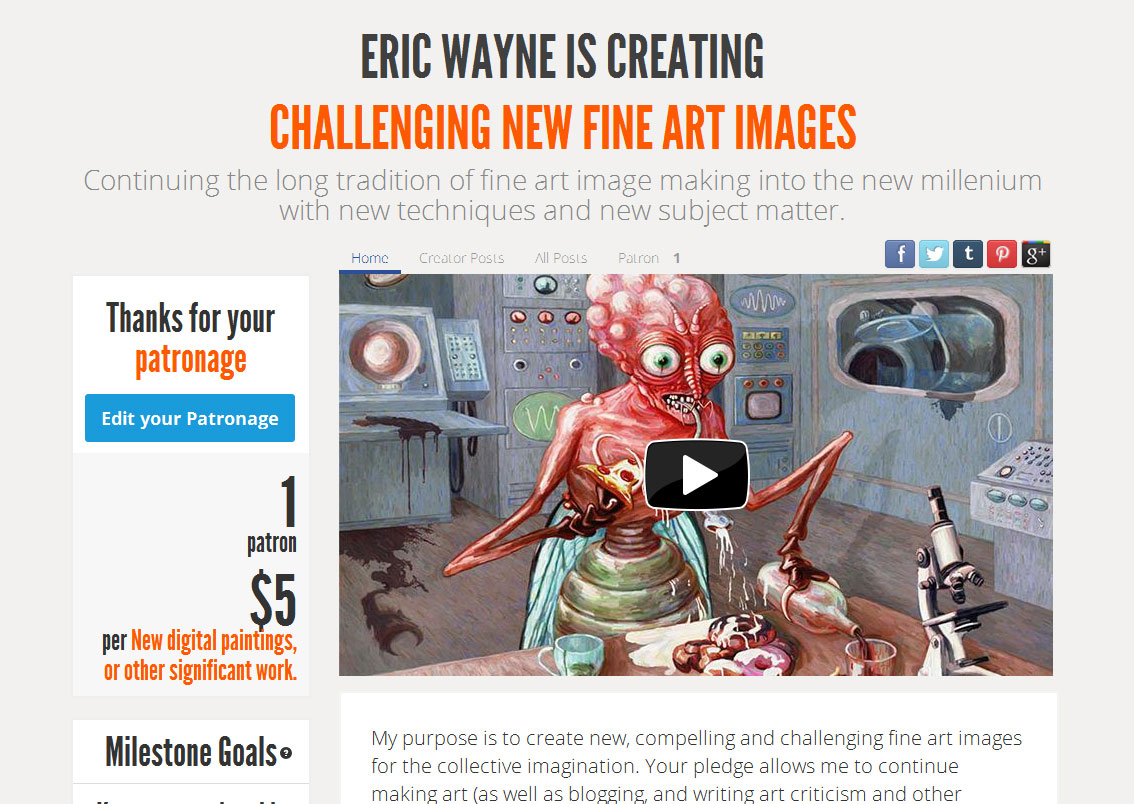

And if you like my art or criticism, please consider chipping in so I can keep working until I drop. Through Patreon, you can give $1 (or more) per month to help keep me going (y’know, so I don’t have to put art on the back-burner while I slog away at a full-time job). See how it works here. Or go directly to my account.

Or you can make a one time donation to help me keep on making art and blogging (and restore my faith in humanity simultaneously).

It’s interesting your writing. Anyway dont’ forget the money, it’s because of that the most of people in professional worl of art talk, communicate, and make art. They speak about soul looking to the pocket.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And I think you’re right about that. We’ve heard forever that “money is the root of all evil” and while that may not be 100% true, it’s probably at least 50% spot on.

LikeLike

As a (ahem…) painter this article certainly resonates with me. I do also appreciate how you can look at a lot of these conceptual types without denigrating their work. However, I couldn’t help chuckling at the last sentence you wrote. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are a lot of painters, like the Stuckists, who will say that conceptual art isn’t art. I just say it’s not visual art, which it patently isn’t, especially when it calls itself “anti-art” and derides the visual.

That said, I can come down pretty hard on conceptual art sometimes, when it is specifically designed to attack visual art and be important for doing so.

I’ve done conceptual, performance, and installation art myself. I didn’t get that 10K fellowship at UCLA for my paintings, and wasn’t admitted to grad school for them, either. So, I get it, I just prefer painting.

LikeLike

What a great post. I remmber being young and looking at museum art and there’d be some pantings that just puzzled me because I didn’t understand. Then later on I realized thats the beauty of art. Art is freedom of expression. You give twenty artist the same theme and its never the tools that I”m interested in. I was but I know better now. Any way what gets me every time is thought. Why the artist created a certain piece. It blows my mind! How we create is like all the animals in the world. Each is diiferent, uniwue, WEIRD and I enjoy every moment of it. The best art that I have created has been when I just let go. I get an idea and just do it. Every time I try and live up to this perfection it’s bad and awful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

…one could write a rather long comment, mostly of articulatory agreement, on many points, which you’d probably … appreciate. Maybe later, probably later. But at least one shortened point to the, or at least a, point: to distinguish communication from language in contexts of evolved and evolving developed motivation of systemic expression. That wasn’t done and largely still isn’t, even in most academic fields. Ie, it’s more intuitive, to me, to consider subjects like music, math, aesthetics or art, as meta-languages (why you can somewhat in turn distinguish prose from poetry or poetical aspects, the later you can see within the same network connections, subsets of cells that fire to only musical aspects of verbal or grammatical language.)

It’s not subjective, though personal culture influences even determinately what anyone is aware of perceiving. Singular languages, ironically, are as inhibitory as not. (sort of why most of the better, I use the word as i those musicians that actually are motivated to say something, even even every other night at 8:30 on cue, instead merely playing… get drunk beforehand: to inhibit the ‘top-down’ (gaba) inhibiting networks by knocking them out.) The DFM, (and others, discoveries ongoing) had been a bit foolishly, not to say stupidly, dismissed for… well, well over a decade. Only lately have repeated study results sort of overwhelmed neuroscience as a field (or fields) forcing them to backtrack or, as they say in Italy, ‘discover hot water’ (which is usually followed by ‘when they find the pasta, tell them to throw it into the pot’) Or, in antique US English, ‘No shit, Sherlock’. It’s that satisfying of multiple systems, each with they’re own language, reflected in developed motivational networks (dopa) and their inferential physiology (brain, rules on top, meanings below.)

I recall seeing a rather extensive exhibit on your ex prof. at… I think the downtown Guggenheim (nyc, before it closed) though it might have been at the New School. I’m afraid, despite my willing, trying, to reach for… some sort of meat, the word which, confirmed seeing his stuff elsewhere, most came to mind was and is: dumb. Less than empty, really, the commentary mistaken, presumptuous, sort of like… Nancy Pelosi. The form, fine. But there’s a substantial, as in substance, differences between, say, Pollock’s languages (new, to express and reach,) and… a pig mask in a cage twerking through splattered shit. Sort of reaching the same way oppositely, with, instead of without, technique, many (too) hyper-realists (so en vogue. At least they do have to work.) No meta. Only… potato chips.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Tonno:

Thanks for the in-depth response. I’m not sure I got quite what you were saying about metalanguages or the multiple systems each with their own language… I think I have a vague idea what you are getting at.

“I’m afraid, despite my willing, trying, to reach for… some sort of meat, the word which, confirmed seeing his stuff elsewhere, most came to mind was and is: dumb.”

Well, yes, there does seem to be a very fine line — some might say imperceptible — between the unfathomably brilliant in contemporary art, and the utterly insipid. You don’t see that much in other mediums. I don’t think anyone ever suspected that William Faulkner might be a moron. But art crtic, Robert Hughes boldly stated that he thought Andy Warhol was stupid. I ten to think it was an act on Andy’s part, but, again, so much of his art is only really impressive if you look at it a certain way and give him a lot of benefit of the doubt. Most would disagree with me on that, but it does tend to be that a lot of the most respected 20th century art is of the “gesture” variety, as in it’s not the art itself that impresses us, but rather how we think about it (the best examples is Duchamp’s “Fountain”). I strongly tend to like the art that is inherently compelling, rather than only compelling in a certain exterior context.

You can chech your suspicions about McCarthy against this artwork and him talking about it in this short video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CyoArCL7byE

I think I agree with you on the difference between Pollock’s canvases (I”m a fan) and “a pig mask in a cage twerking through splattered shit.”

Thanks again for reading and commenting. Feel free to elaborate and set me straight it I misinterpreted any of your text.

Eric

LikeLiked by 1 person

…thanks for the link. Still don’t, I that is… though ‘open’, relatively…. find any different flavor. Actually, that sort of granular, mud-gray, plane flavor gets stronger, the same reaction of a long time ago. The ‘getting inside’, fine, great… sounds like a line from Price (American Psycho,) with the difference of course that… there’s a notion and reaching in that written work, even if a bit rhetorical, a sadness, a hunger. (I use that as a writing compare for… it sort of corresponds, in some ways. That novel, as well, provoked rather polar reactions in its excess, which in English sort of overwhelmed the whole. The Italian translation was instead… marvelous, actually much, much… better, in all respects, than the original. You could say that translation corresponds a little to the M’s ongoing sculpture, the new weight breaking the underlying original’s form for a more interesting result.) But it’s… still… dumb. Self-referring. An overcooked steak. And he, a bit ironically funny, to me, in his obvious ‘sculpture-getting-in,’ compared to Michel. B’s ‘letting out what’s already there inside.’ Or, if you will… if I recall, the Davide took 3 years to chisel. By hand. Working alone. As of filming…M’s had been 2 years in the works. With modern materials. And staff. True, both do have ball sacks. But… Maybe unfair, the compare… then again, maybe not.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You might be being a little generous here. I shared that video in order to confrm your suspicions. Imagine have a 10-week course with him as your instructor, and when you were in your 20’s.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love the evolvement (sp?) of your thought process, Eric!

Esp liked,

“The researchers see this as proof that, in the words of the narrator, “our experience of beauty involves connecting our senses and emotions with something personal. Our sense of self.”

&

There’s something about being moved by paintings that forces us to be self-reflective. That may be the biologic signature of what it means to feel moved by a painting. ~ Anjan Chatterjee”

Glad I stopped back in to take a peek, lol! All the best, Eric 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

And thanks for stopping by Felipe. Glad you enjoyed the article!

LikeLiked by 1 person