Y’know, I might have walked into the In Pursuit of Beauty room in The Manchester Gallery, and thought, What’s with all the nymphs and nudes and beauties? It would be kinda’ like watching an old episode of The Honeymooners and wondering if it wasn’t supposed to seem abnormally abusive the way Ralph always yelled at Alice, thrust his finger in her face accusingly, and threatened to send her to the moon with a punch to the kisser, all the while delivering feigned blows within an inch of her nose. Someone could make an art or film piece examining Ralph’s behavior from a feminist perspective and I might appreciate it, but if they demanded the show be taken off the air or insisted it was only about sexism I’d end up having to defend Ralph and the creators of the show. That’s pretty much what’s happening here. As often happens, you lose people who might be open to your stance when you overstate your case or resort to drastic measures.

Even after Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs was put back up due public outcry, artist Sonya Boyce defended removing it, denied it was censorship, and insisted on the validity of her art as action. I guess nobody expected an apology, or a, I may have gone a wee bit overboard, or anything other than the artist digging her heals in. This is just the latest in a series of incidents in which the far left (one might use the word “militant”) has aggressively sought to censor or even destroy artwork. I say they have gone too far, so has Boyce, and they need to reel themselves in.

I lived in Brooklyn in 1999 when the Sensation show came to the Brooklyn museum, in which case I was able to just walk over there and take in the latest wave of British art, including Hirst’s shark tank (which is not to say I’m not very critical of Hirst). When I exited the museum I was greeted with a gaggle of protesters, a lot of them of the religious variety, who were upset by Chris Ofili’s Holy Virgin Mary, which incorporated elephant dung, including as one of her breasts (not to mention lots of cut-outs of buttocks).

I argued with them for a while even though I knew it was futile, and then picked up an everything bagel and a cup of coffee. Well, I feel about the same in relation to those protesters as I do to Sonya Boyce. She shares with them the demand to shut down art that she finds offensive. For them, they were doing the lord’s work, and for her, she’s doing the load’s work (as in a load of bollocks). Just kidding, sorta’. She’s doing art as action in the name of social justice and bolstered by critical theory. She hasn’t come out and said exactly this, because those words are as loaded and pinpoint accurate as censorship, and it’s just handing people ammo.

I think most people would agree that we need to sign a social contract to be a part of civilization, and social justice is a good thing. We might just disagree on what is really just and what isn’t. And when it comes to critical theory, we should, I’d think, defer to the theory that is more critically sound. Thus, under the auspices of social justice and critical theory, let’s have a look at her arguments and see if they really are for the nobler cause.

The title of her article, published in the Guardian, is Our removal of Waterhouse’s naked nymphs painting was art in action. The two most critical things here are the inclusion of the word naked and the idea of art in action. Naked is an exaggeration because the nymphs are mostly underwater, and practically the only thing you see of their bodies is their heads, arms, shoulders, and some modest breasts. So why say in the title that they are naked? This is as odd as describing Jacques-Louis David ‘s The Death of Marat as full frontal male nudity. Presumably Marat is fully exposed, on the other side of the bathtub. It’s a bit disingenuous to refer to the nymphs as naked right in the title, and that makes me suspicious. It also plays into the hands of people who would accuse Boyce of Puritanism and prudishness.

What does art as action mean? She doesn’t mean anything like Action Painting (a la Jackson Pollock), and isn’t referring to physical action really, though it does involve some. She means political action. And while art as political action is more clear than art as action, it is even more clear to say political action as art. There was a bit of obfuscation here. Compare her title, and what it really means.

- Our removal of Waterhouse’s naked nymphs painting was art in action.

- Removing Waterhouse’s nymphs was political activity as art.

My version, I think, is much more accurate.

The subtitle claims: It was about giving people a say in what’s on show.

This is a very curious assertion because she removed the painting BEFORE the public had any say in it. They didn’t even get to see what was removed in order to judge for themselves, since both the painting and reproductions of it in the gift shop were removed. Instead, they were treated to a hand written statement accusing: This gallery presents the female body either as a “passive decorative form” or a “femme fatale”. Let’s challenge this Victorian fantasy!

She didn’t ask what visitors thought the gallery presented. She took down the painting (and the postcards…) . She gave us the reason why. And then she just gave sticky notes for people to respond on. How can the public say anything meaningful on a sticky note? My guess is the artist anticipated high-fives in linguistic form.

Her topic paragraph is similarly opposite to the truth: Every day, in museums all over the world, paintings are put up and taken down. More often than not, this activity takes place pretty much unannounced and unnoticed. In most cases, the decisions that inform this activity are made by professional museum curators behind closed doors.

The decision to remove Hylas and the Nymphs was also made by professional museum curator Clare Gannaway, in cahoots with Boyce, behind closed doors. In fact, Boyce was commissioned to do it. You don’t get much more insider than being paid by a museum curator to remove someone else’s painting as part of your upcoming retrospective at the same gallery. And when a museum gives you a retrospective, can you really bitch about their curatorial practices? Yes you can, apparently.

Her next paragraph is telling for what it doesn’t anywhere come out and say. Boyce argues, again, that removing the painting was an attempt to involve a much wider group of people than usual in the curatorial process. Since the public had no say so in the removal of the painting, what curatorial process is she talking about? This seeming conundrum dissolves when one realizes she’s talking about the whole room, and was hoping to get public support for taking down more paintings, perhaps the whole content of the room. You can imagine what kind of art would replace it, and that a work or two of hers might be among them. The Waterhouse painting was just the tip of the anticipated iceberg.

Her next argument is cringe worthy. I’ll give you a chance to see through this spurious logic on your own: It is well known that the vast majority of artworks held in public collections languish, hidden from view, in storage facilities. Space constraints are one reason, but curatorial choices also play a role. Would we call these choices “censorship”?

See the problem? Here, the critical theory ain’t so critical. By this logic one could say, It is well known that people die in hospitals every day. Would we call these death’s “murder”? That doesn’t mean that if you hasten someone’s death through deliberate action in the prime of life it isn’t murder!

Taking down someone’s art that is in an ongoing or permanent display isn’t not censorship just because all shows must come down someday. By her logic it’s veritably impossible to censor art because any show will eventually end. Derp!

She continues: It is very rare that a range of museum workers… let alone visitors, are invited into a dialogue about what goes on or comes off the walls, or why. Giving visitors sticky notes after the fact of taking a work down, and telling them why, doesn’t allow for much of a dialogue. Again, I’m pretty sure she envisioned the public would have been overwhelmingly on-board and more works would have come down. All hail!

Then there’s this curious tidbit: Judgment is at the heart of art, and this type of engagement has wide cultural implications. What is beautiful to some people may appear to others to represent a problematic and pejorative system.

Judgment is at the heart of art? What kind of judgment? Does she mean aesthetic judgment? Well, no, because she’s said precisely zero about aesthetics in her judgments. She means judging whether an artwork is socially problematic, a.k.a. politically incorrect. So, judging whether or not a work of art is politically correct according to identity politics is at the heart of art?

If you object to the term identity politics because you think it sounds negative, than we can define it according to Boyce’s own words: intertwined issues of gender, race, sexuality and class which affect us all.

Uuuh. No. Identity politics is at the heart of social justice and radical politics, obviously. It’s rather a stretch and über convenient for political activists to say that it is also at the heart of art.

You can test this yourself. Peel back the years and remember when you were a kid listening to music. Did you enjoy your favorite songs because of the judgment implicit in their political agendas? I can remember, for example, the first time I heard the Beatle’s Hey Jude. I really liked the Naa, na, naa, naa, nanana-naaaa, nanana-naaaa part. If you can tease a political judgment out of those lyrics, you can exact a confession from a skull.

Where some gallery goers see beautiful paintings, Boyce sees a problematic and pejorative system. Oddly, she hasn’t allowed that one could see both. And of course she’s not going to raise the question of whether the problematic and pejorative system could be projected onto the art rather than excavated from it. Let’s just stop and think about this for a sec. Boyce apparently believes the Pre-Raphaelites were a group of artists who were motivated to make art that was a pejorative system. How often are artists motivated by such low purposes? These are artists that have stood the test of time, mind you. Seems highly unlikely to be a real motivation, consciously or not, to me.

Significantly, Waterhouse is considered part of the “Aesthetic Movement” [as well as in league with the original Pre-Raphaelites, and a Classical Romanticist]. A paragraph from The Art Story sums up the movement rather nicely: Aesthetic artists touted the adage “art for art’s sake,” divorcing art from its traditional obligation to convey a moral or socio-political message. Instead, they focused on exploring color, form, and composition in the pursuit of beauty.

Here we are well over a hundred years later, and we are back to insisting that socio-political messages are at the heart of art. Boyce’s condemnation of Waterhouse’s painting represents, among other things, a moralistic attack on art for art’s sake. Oh, how utterly refreshing?! Note that the most famous artist of the movement was America’s own James McNeill Whistler. His Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl of 1862 might also be considered to merely make the female body into a passive decorative form. We’ll have to move this painting to the basement as well.

In order to make her moral case, Boyce mentions another offensive painting in the gallery: On the opposite wall to Hylas and the Nymphs there is a topless depiction of Sappho by Charles Mengin (1877), where she stands on a cliff edge about to commit suicide due to her failed heterosexual love for Phaon. Nothing in the painting suggests her prolific and influential role as a lyrical poet, or her status as a lesbian icon.

If one were to take ones eyes off of her breasts and look at what she’s holding in her right hand one would discover a rather large musical instrument, a lyre to be precise. Would a lyre be something that suggested a lyrical poet? Yes, it would, quite obviously. Don’t know how Boyce missed that. Here, again, the fault Boyce finds in the Aesthetic paintings of more than a century ago is the failure to express the present sociopolitical agenda she subscribes to, which is even more ridiculous when one recalls they were trying to avoid all moralizing.

Boyce continues: Some museums – I suppose the type I am most interested in – consider the museum as a place to explore new meanings and to forge new relationships between people and art.

I think most people associate museums (unless they are contemporary ones) with showcasing historic art rather than examining new meanings and relationships. Boyce’s expectation is about as sensible as going to vintage clothes stores to look for the latest fashion.

She goes on: In my mind, the past never sits still and contemporary art’s job is increasingly about exploring how art intersects with civic life. Art has a job here, a responsibility if you will, and it’s to mold civic life. In other words, the purpose of art is political activism, and social justice activism to be more precise. And this is increasingly so. I’d counter that it is only so because far left political activism has increasingly hijacked the art-world to serve its radical agenda. Much of the art world wants nothing to do with all that moralizing, nor is it necessarily on board with a far left political agenda. The idea that all art is increasingly subordinate to a radical political agenda nicely serves the objectives of said radical agenda.

And then Boyce makes a claim that shades into the most popular of logical fallacies, the ad-hominem attack. She writes, In the professional media and at supersonic speed across social media, there has been much outrage and some bigotry spurred on by the rhetoric of “censorship”. Here, if you accuse that she is guilty of censorship, than you are potentially a bigot. This is attacking you, rather than your argument, and defining you as a person who is automatically wrong, in which case we don’t even need to hear your argument. You are a bigot and whatever you say is bigoted.

Boyce writes, Proclaiming that art is being censored or banned has had a polarizing effect on the discussions. Here, she claims those who see her take-over of the gallery and removing a painting as censorship are the problem (and bigots). This is a difficult argument because her action is the dictionary definition of censorship: Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information, on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, politically incorrect or “inconvenient” …

Boyce actively suppressed a work because it was politically incorrect. I think people can be forgiven for not appreciating the rhetorical back-flips through flaming hoops one has to make to come to the desired conclusion that textbook censorship is not censorship at all. You see, the reason it’s not censorship is because it’s censorship AS art (never mind that this would also allow murder as art to not be a crime).

She continues: There is a whiff too of that old chestnut: the innocent and reassuringly familiar past (historic paintings) pitted against the vacuous emperor’s new clothes (contemporary art) — which is simultaneously presented as a prudish form of feminist moralizing. The first problem here is the denigrating notion that art of the past is innocent and reassuringly familiar, which it only is if one has no real appreciation of it. If one finds Goya, Daumier, Bosch, Dix, Bacon, Kubin, Beckmann, Kollwitz, Schiele … innocent and reassuring than one is critically myopic.

The second problem is making this a straw man argument. Those who are critical of her conceptual art piece (including me) are portrayed as dismissing ALL of contemporary art as vacuous. You can be a fan of contemporary art in general, be a contemporary artist, and still think her piece falls apart because of conspicuous logical inconsistency and threadbare execution (a written sign affixed to a wall with masking tape).

The third problem is how her statement belies itself. Here she tries to say the issue is that the people who like traditional art are attacking contemporary art, but she has attacked them as only liking traditional art because it is reassuring and innocent. What we have here is the opposite of what she contends: contemporary conceptual art is attacking traditional visual art while openly ridiculing it. She is the one who both in removing the painting and in this statement pits conceptual art against painting. She’s doing the equivalent of saying, his face hit my fist.

Boyce doesn’t bother to attempt to refute the claim, assuming merely characterizing it as a whiff too of that old chestnut will do. Characterizing an argument, and presenting a straw-man version of it does not constitute any sort of persuasive argument to the counter. One could respond to that level of argument by referring to her stance as reeking of Postmodern gobbledygook. It’s just name-calling.

When it comes to accusations of prudishness and feminist moralizing she just tucked that into the whiff of an old chestnut that is noticing that her removal of a painting smacks of conceptual art perpetually attacking painting in order to seem radical (which, if you recall, is how conceptual art started with anti-art). Here she believes she’s dispatched three arguments with just one meaningless and insulting characterization.

She will need to do much more to escape questions of censorship, conceptual art attacks on painting, moralizing, and Puritanism/prudishness.

A huge irony in this whole story is that the decision to take down the painting was an inside job, cooked up in cahoots with a gallery curator, and when the public became involved in the dialogue they overturned the take-over of the room. This could indicate that Boyce & company never really wanted the public at large to be involved, but rather just a much smaller coterie of like-minded activists.

Taking down art and then asking visitors in the museum to support doing so is not giving the public any say so, and thus doesn’t strike me as justice under the conditions it asserts for itself. Neither the arguments supporting the work, nor Boyce’s answer to criticisms are logically sound (one argument is laughable, and the others are mere assertions, confusing and/or logical fallacies). Therefor, If the goal is social justice, than this conceptual art piece doesn’t qualify, and the critical theory underpinning it is insufficiently critical.

As a failed piece of conceptual art the art as action never deserved to hang on the wall among time-tested, Pre-Raphaelite paintings, let alone replace one of them with itself as a precursor to removing all of the paintings and replacing them with similar political activity as art masterpieces.

If Boyce’s real object was just to open a dialogue about curatorial practices at the museum, there was probably a much better way of doing it. And I’m guessing that the room in question probably isn’t up to present day feminist standards, and there might be an interesting way to examine that without removing work or applying reductionist and belittling standards to it. What she did was the equivalent of executing a prisoner and then involving the public in determining his guilt or innocence. If people got the wrong impression, maybe it was because the art in action itself gave the wrong impression. The intent may have been good, but the result was social injustice in the art world.

Justice, on the other hand, was served when the public actually got a say-so in the curatorial practices of The Manchester Gallery – not via her sticky notes but via social media and other routes – in which case they chose to take down not Waterhouse’s painting, but Boyce’s protest art.

The least we can ask of social justice art (before we hang it in a museum in place of a masterpiece) is that it is both just and art. And if it fails on both counts we don’t just get to say it’s because the critics are hopelessly backwards and bigots.

As far as critical theory, logic, reason, or evidence is concerned, her political activity as art project is neither socially just nor actually liberal: it has slipped into a radicalized, extremist and authoritarian ideology that seeks to suppress art and artists it doesn’t like on largely spurious grounds in accordance with its overarching political agenda. It is a sad state of affairs when art institutions, art magazines, and the art world in general is bullied into submission, goes along with this trend, or even worse when artists themselves launch the attacks.

It’s time for artists and the art world to stand up to extremist politics and calls for suppressing art, whether those attacks come from the religious right, ultra conservatives, or radical left wing extremists (yes, even if they are non-binary women of color).

~ Ends

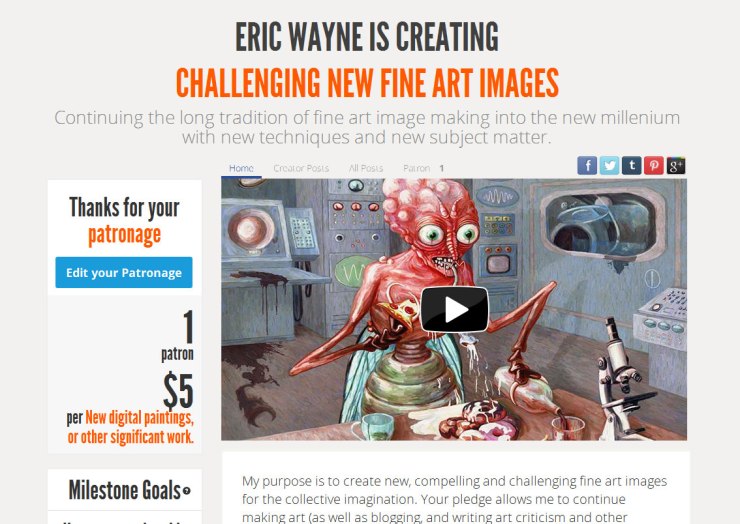

Funding. Through Patreon, you can give $1 (or more) per month to help keep me going (y’know, so I don’t have to put art back on the back-burner while I slog away at a full-time job). Ah, if only I could amass a few hundred dollars per month this way, I could focus entirely on my art and writing. See how it works here.

Or go directly to my account.

Or you can make a small, one time donation to help me keep on making art and blogging (and restore my faith in humanity simultaneously).

If an advertisement appears below, I have no control of it and get no proceeds.

Eric,

Well at least the public got the final say in this, but I’m afraid we’re getting close to burning books and paintings again. Duluth, Minnesota just banned To Kill A Mockingbird from all public schools because it has a word in it that makes people uncomfortable. Soon we will be walking into museums with empty walls, because no paintings were deemed ok to look at. But they can call the entire place a conceptual work of art!

I do wish we had more of a say in what paintings come out of the basement though. The walker has a Francis bacon of Pope innocent X in the basement that I don’t think they have ever displayed. They could put out a list of 10 or so paintings they have downstairs and let the public vote on what they want to see. Just an idea.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Aaaah crap! I loved “To Kill a Mockingbird” when I read it in Jr. High. The left has gone nuts. This is a power grab, and ordinary people need to stand up to this even if there is a bogey man at the opposite end of the ideological spectrum to contend with.

Ah, your idea of what comes out of the basement is NOT what Sonya Boyce wants at all. That last thing she’d want is for the work of another white male to be on view. This is about putting white males art in the basement in accordance with a political agenda. It’s not really about the people having a say in what they want to see, especially now that we have seen the people don’t really want classic paintings replaced with propaganda.

Now I have to look up the Duluth censorship thing, or was it conceptual art?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your past few articles have been great. Thoughtful as well as entertaining. I myself am a huge fan of Pre-Raphaelite style art, and would be really disappointed if I visited that museum and this piece was removed.

Reading this article actually sent me on a Pre-Raphaelite kick. I just finished up a BBC documentary about the founding members (which was decent), and am currently searching out a copy of the Moxon Tennyson. I appreciate your articles for introducing me (or in this case reminding me) of great artists!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Jordan, it’s great to hear that! And, for me as well, this controversy has re-ignited my interest in the Pre-Raphaelites, and I, too, watched some documentaries on them. The more I look at “Hylas and the Nympths” the better it gets.

LikeLike

Eric, great analysis of sham political activism pathetic masquerading as conceptual-art. I find it especially interesting that her attacks on both the art she takes offence at, as well as her critiques so closely match the antics of both the Nazi & Stalinist Communists vendettas to purify Art to better sever their totalitarian societal vision.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. It’s interesting how sure she is that she’s right, as well.

LikeLike

I agree with what you are saying here. Your last blog was, however, was calling for getting politics out of art.

I take it that you mean that we should get political correctness out of art. Politics is everywhere and in the smallest details of our lives. It cannot be gotten out of anything. All we can do is be aware of what the political bias is.

An example? The portrait of Michelle Obama for the Smithsonian Museum of American Arts. Not an expert portrait and one which appears to have resulted from a politically correct and a political decision as to who to choose.

Not good. Agree?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I elaborated what I meant pretty well in that article. In short I meant to stop looking at art primarily through a political lens (which presently so happens to be a radical left lens), and making art through that lens. To do so completely subordinate art to this or that political agenda and robs it of any inherent power, which it actually has and is what really gives it its worth. If one thinks art has to have the right message to be good, one misses the point of what really makes art good.

LikeLike

Think I will stay with Marcel Duchamp: the people who look at art make the art on condition that they have educated themselves on the artist and on the art tradition.

LikeLike