What is Real in Art: With a Revaluation of Brian Ashbee’s Infamous “Art Bollocks”

So much of the art of the recent past can be seen as attempts to get away from mere images, and confront the viewer with the real… ~ Brian Ashbee, 1999.

The real in art is the evidence of self-awareness, or levels of self awareness communicated by the piece. Just as in life, whatever is most self-aware is most real. You can see this self-awareness obviously in Shakespeare’s plays, Rembrandt’s Self Portraits, or Beethoven’s Piano sonatas. Aliens who discovered these peices would know they were dealing with a self-aware species. Curiously, what is seen as real in art (and the universe) is inert objects within your physical space (a urinal, a balloon dog, a Brillo box) that require interpretation on your part. They don’t in themselve’s communicate self-awareness. It’s like a record that when you play it there’s no sound, but the needle still moves across the record, and people consider this the best music, because it makes you think about music. Let me go into more detail.

If you don’t know, way back in 1999 (which I always associate with the imaginative projection of the future that was the sci-fi series “Space 1999”) a little known thinker took it upon himself to unravel conceptual art and the art criticism that propped it up. Brian Ashbee had studied art and criticism, saw something wrong, wrote about it, and lights came on all over as people recognized some of the truths he unveiled. This work is his now infamous: “Art Bollocks” [which you can read here]. Someone just recommended it to me, and while I’d read it years ago, and was a fan of his blog until he stopped posting in 2016, by now there are some new thoughts and insights I’ve had that have changed my relation to it, things I’d like to add that make a difference, and perhaps lend his argument more power.

His writing is pretty damned clear and accessible, so there’s no use trying to encapsulate it. Thus I will share some bits directly which can’t be articulated more succinctly. Here’s the intro.

“A picture is worth a thousand words”. Vision is primary, according to this view, and language secondary. But not any more – not, at least, in the visual arts, where the experience of the work is often meaningless without the critical text to support it. This is especially true of much installation art, photography, conceptual art, video and other practices generally called post-modern. Why are these forms so dependent on theoretical discourse?

Traditional arts, up to and perhaps even including the abstract art of the 1950s, involved the construction of a relational model of the visual world. A picture. An alternative strategy to modelling the real, and much favoured today, is simply to appropriate it. This typically involves the use of actual objects – not images but the thing itself.”

This seems fairly accurate, but we are in the realm of philosophy here, and few of us are learned enough in the discipline to really grapple with these ideas, and those who are can be so far out on a limb of their choice that whatever they’re saying is lost on most everyone (Is Slavoj Žižek even trying to make sense, or just be outrageous?). Contemporary artists, like me, got an education in postmodern philosophy and critical theory (I got an “A” in a coarse with that title at UCLA, and it was much easier than my more conventional Intro to Philosophy class I took in community college one not-so-fine summer). We are given articles, photo-copied chapters out of books, Xeroxed “readers” from our professors, and so on to discuss (and rarely if ever debate) in graduate seminars. But all of this is admittedly rather piecemeal and UNDERSTANDING it really just comes down to being able to approximately use the requisite, regurgitated vocabulary – words like “signifier” and “reification” and “commodification” and “simulacrum”.

Coming out of these institutions, and having some famous professors (Paul McCarthy is probably the most famous), I can tell you virtually none of them are themselves philosophers on any level, and don’t go in for reading the whole books by Baudrillard or Lyotard or Derrida… Mostly, to be honest, we artists regurgitate half-digested bullshit we’ve consumed from a banquet of samplings. In this case, the artist/philosopher is rarely anything of a philosopher at all, and most likely has no significant exposure to any philosophy prior to Postmodernism. And this is why if someone bothers to do a bit more foundational plunging into philosophy, or anything other than Postmodernism, and is pretty good at analyzing arguments, she or he might be able to rather easily shoot major holes in the armor of critical art theory.

Ashbee goes on to quote Gerhard Richter:

“The invention of the ready-made seems to me to be the invention of reality; in other words the radical discovery of reality, in contrast with the view of the world image … [Since] then, painting no longer represents reality, but is itself reality …”

This most likely would have been a defense or description of a form of non-representational painting in which the paint itself is paramount, and a fact that can’t be ignored. You don’t look through the paint at an imagined world, but AT the paint as a factual thing in your physical space.

There’s something terribly wrong with this idea of what reality is, and Brian Ashbee didn’t address it in his essay. My main object today is to question which kind of thing is more pregnant with reality, more REAL. And I would notice in the rather stunning Richter above, that while the physicality of the paint is inescapable, the aesthetics, dare I say beauty of the very deliberate mixtures of colors and textures delights the eye, even when you are looking at a digital copy on your monitor. There’s no paint here, and no “reality” of the kind that is supposed to be the ineradicable fact of art. And yet, there it is, another kind of reality staining through directly into your mind. I will explain why this is a greater reality in short.

My argument above brought back a memory of the first time I saw a work by Willem de Kooning. It was when I was 18 and in a drawing class at L.A. Valley College. The teacher opened a book or magazine and pointed her finger at de Kooning’s “Door to the Window” [below]:

I think my jaw dropped from half a room away, looking at a reproduction in CMYK colors, in a page in a book or magazine. I hadn’t seen anything like this before, and I was truly impressed and inspired. But it wasn’t the physical paint, the size of the image, or any of that stuff. No “field” of color to those colors, unless the field were a square inch or two. No presence of the THING in front of me. It was just a reproduction of the image, and it knocked my socks off. On a side note, near that time, as I brought home more and more art publications from the school library, I contemplated if I could just manipulate the ink directly and bypass the more clumsy painting process. This I now do in my digital paintings.

Ashbee continues:

So much of the art of the recent past can be seen as attempts to get away from mere images, and confront the viewer with the real. But the attempt may well be doomed because it seems to me that art based on appropriation of the real requires language to make it meaningful in a way that art based on picturing the world does not.

I, for one, don’t much like standing (though I love walking), and standing up to read paragraphs-long placards adjacent to an otherwise incomprehensible object of art is a tiresome activity. Guaranteed the majority of my mind will be fantasizing about having probably the cheapest thing on the menu in the closest cafeteria. “One coffee please. Um. Americana (’cause that’s the cheapest one)”. Ah, to sit down and people watch while pondering all of this and vaguely wishing I was off doing something else. Ah, let me look about distractedly to scan for pretty women.

Ashbee really hits it home with this next paragraph:

Take the first case of appropriation in the history of art: Duchamp’s ready-mades, mentioned by Richter. The urinal of 1919, signed by Duchamp “R. Mutt”, is not a model of the real world, nor is it a picture; but what it is modelling, and subverting, is the art world. This is not art to be looked at; this is art to talk about and write about. It doesn’t reward visual attention; it generates text. In that, it is the model for much art since the ’60s, which we have come to call post-modern: art as a machine for producing language.

That brilliant encapsulation is what set so many lights off in people’s heads. I imagine little red lights, like on vintage computer panels, say in the transporter room of the Enterprise. Bing. Click. That makes sense. Well, I’m sure it’s actually much more complicated and messy, but, there’s a kernel of truth in this that we can’t just flush away.

And I can’t stand to look at that [expletive of choice] urinal anymore, but that will be my point in resurrecting it’s putrid carcass once again. Blah!

Please indulge me in a wee tangent here. Notice above how badly, sloppily, and uglily Duchamp signed the urinal. This should make it apparent that it was intended at least in large part as an in-your-face, irreverent prank. For those that don’t already know, this work was submitted to an exhibition in which all works were accepted provided the artist paid the entrance fee. Duchamp was appalled when this work was not accepted on the grounds that it was indecent.

Above is an artwork by a contemporary artist who put the urinal back into the men’s room, where I gather he thought it really belongs, though there’s probably more here than meets the eye. [for my article on this artwork, go here]. A deliberate flaw in the design of this re-recontextualization of “The Fountain” is that when you piss in it, if you choose to, because it is on it’s side, your urine comes out the hole in the front and onto your legs.

Above is an artwork by a contemporary artist who put the urinal back into the men’s room, where I gather he thought it really belongs, though there’s probably more here than meets the eye. [for my article on this artwork, go here]. A deliberate flaw in the design of this re-recontextualization of “The Fountain” is that when you piss in it, if you choose to, because it is on it’s side, your urine comes out the hole in the front and onto your legs.

What is real?

Ashbee didn’t, at least in this article, question whether or not a urinal constituted the REAL more than did a painting. It’s as if he, or we, as in everyone, just takes this for granted. A thing, any banal object, in real space is more tangible, empirical, and inescapable than anything conjured in an image. Surely a stone is more real than a fleeting image in the imagination! Your daily life is more real than your dreams, for example, no matter how real the rare dream might have been (if you woke up in terror it was probably too real), because it has consistency, you can return to it, and you can’t make it go away.

Duchamp, significantly, asserted that he wanted to do away with art as religion had been done away with. See a handy graphic I made for this quote below:

Art, like religion, were, from Duchamp’s perspective, creations of the imagination, fantasies, projections upon reality, or alternative realities. Science has shown as “true” that which can be produced and repeated in a controlled experiment, corroborated by other scientists, and not debunked in peer-reviewed, professional, scientific journals. And these sorts of facts, these sorts of truths, brought us the automobile, the airplane, the telephone, electricity, the television, and in total our modern lifestyle. Why cling to outmoded superstition and visual articulations of the fantastical inner minds of artists?

Duchamp offered us the thing itself. He gave us simple objects of incontrovertible reality, humble specimens which if we were to contemplate them we contemplated unalloyed reality itself.

Reality, Duchamp would have us understand, is an inert physical thing.

Duchamp’s “The Fountain” dates back to 1917, and I just realized this second that the urinal isn’t really a fountain at all, almost the inverse, in which case the implicit fountain is the penis. Oh, it really is an FU to the art world, art, and artists. Witty, witty guy that Duchamp. I only wish he were wittier. I like a good laugh where I can’t stop laughing, and am less for the dry chortle. Maybe I had to be there. His breakthrough which has been compared to Michelangelo’s painting of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel AND the best innovations of da Vinci, issues from 1917, or, 100 years ago. I’m planning a longer article on this, so will keep it brief here. [I’ll dig up all my quotes then, but here’s one I have handy.]

Duchamp has been compared to Leonardo da Vinci, as a profound philosopher-artist…” ~ Martin Gayford, for The Telegraph.

1917 (The year the fountain changed everything)

Let’s just take a quick look at some of the other pieces of art that were produced that same year. These things are so easy to do with Google.

We can start off with something from the complete opposite end of the spectrum, Max Beckmann’s “Descent From The Cross”:

And here is a sampling of other creations, including our star, “The Fountain”:

Never mind for the moment, Monet fans, which is your favorite image or artist or who the paintings are by and what context. Pretend we don’t know. Pretend you are an explorer from a future civilization or an alien civilization. Which piece(s) would be the most valuable to you?

What would be the best find to tell you about the people, the civilization, and the minds of the lost civilization? To make this even easier, if it isn’t obvious, compare these two things:

- A chamber pot from roughly 1600.

2. Any old copy of Shakespeare’s King Lear, originally written at about the same time (@ 1606).

Aliens visiting our desolate future Earth, upon discovering a chamber pot from 1600 and a copy of King Lear would consider King Lear infinitely more valuable. One of the artifacts encompasses the other. The chamber pot tells the aliens that we humans shat and pissed and came up with a convenient place to do it other than just on the floor or all over ourselves. It tells them we were able to use our hands to make a bowl, and that we could fire it in a kiln. They would probably assume that we knew back then that this was a factual sort of thing, incidentally.

If you don’t know much about me, I lived in China for over 4 years, in a city that would be considered not itself “rural”, but a bit of an oasis in an expanse of rural countryside. I will spare you my horror stories of the worse toilets I encountered in the country, or give you graphic images of the habitual habit of not flushing, and merely share that I had a squat toilet in my last apartment. If you are not familiar with one, there’s no water in it until you flush. Well, I never really understood my own waste until then. Again, I will spare you the details. My point is that nobody ever needed to be reminded of the corporal reality of a urinal. If you even say “WC” in a classroom full of Chinese children in China, they almost automatically laugh, because they are well familiar with this inescapable horror (and in parts of China it is needlessy horrific, I assure you).

The aliens could extrapolate from the chamber pot perhaps a lot of things, such as that we might have exchanged or sold these items, that the handle indicated we had an appendage that could lift them, and on and on.

King Lear, on the other hand, would let the aliens know (and there’s enough language there for them to decipher the old English) that we lived in complex societies, had inner lives, ulterior motives, reason, doubt, emotions, inner turmoil, moral quandaries, lust, beliefs, understood tragedy and comedy, and were deeply philosophical. They would know that we were eminently conscious and contained within our minds, and could relate, an extraordinarily complex model of the universe.

From an alien perspective, which item were more “real” would be the one which showed more clearly the “human stain” – the imprint of what essentially made us human. One object contained traces of feces and urine. The other was a manifestation of our inner worlds, imagination, and gave not only any fact they’d need pertinent to the chamber pot, but gave the context within which it was used and considered.

One object is evidence of a certain level of intelligence and awareness, tool use, managing waste, probably hygiene, and so on. The other is evidence of an extraordinary level of intelligence and awareness from which a whole civilization can be viewed. Note that Shakespeare could probably have learned to make a chamber pot with a little practice, but most chamber pot makers couldn’t have learned to write plays like Shakespeare with years of practice.

Let’s reverse this, just because there are going to be some stubborn people who refuse to acknowledge this point. Imagine the latest Rover on Mars discovers two things which are presumably left over from a crashed alien space ship. One is a glove. The other is a diary. Which is more precious? Granted, if the glove were switched out for a spaceship, the technology and what could be inferred from it might trounce the diary.

Reality, our experience of it and any conception of it ONLY takes place in our consciousness and imagination. Without consciousness, nothing can be conceived of as existing, because there’s nothing to do the conceiving. Therefore reality is NOT the mundane object perceived by consciousness, but is consciousness itself, and its self-awareness in particular. The more an object possess evidence of the magnitude and extent of awareness and imagination, the more real it is.

It is probably easier to just think in terms of intelligence. Archeologists would prefer to discover an ancient artifact that possessed more evidence of the intelligence of the people who produced it. In this way the Egyptian hieroglyphics or the cave paintings of Lascaux are far more precious than an article of clothing or a tool from the same period.

But in terms of art, the sign of intelligence is often going to be the imagination. How far out did the imagination travel to produce a piece? How much imagination is in evidence in the artifact? How much of human perception is encapsulated in that artifact?

When artists act as curators of today’s third-rate archeological finds – a urinal, a comb, a bottle rack, a snow shovel, cheese graters, vacuum cleaners, a balloon dog in high-polished chrome, Brillo boxes, Campbell’s Soup cans, a shark tank, a pharmacy in a gallery – are they really awakening us to reality? Can we not have a same or better experience by travelling to a far off place and walking down a street, lost, where everything is kinda’ new and alien? [I speak from a goodly amount of experience here, and the answer is emphatically yes.]

Or are they putting the brakes on reality, keeping us from using our imaginations, squelching the visual imagination and denying the unconscious? Is the insistence that the banal and vapid IS reality really that profound, or is it profoundly stupid?

How often is the most exalted art flatly benign, deliberately insipid, boring on inception, and completely devoid of any evidence of a rich visual imagination?

Back to Ashbee:

Since the 1960s, we have witnessed the complete institutionalisation of the avant-garde. Our major institutions are devoted to cutting-edge art. Apart from a brief flurry of expressionist painting in the ’80s, most of this has been in the areas of conceptual art, photography, video and installation. This is the work that people in power in our institutions deem to be significant. It gets written about, funded, and shown. It is the Official Art of our time.

This fits my experience including going to art school though the grad level. And much of that art does not engage or employ the visual imagination in the slightest, nor does it want to, nor would it be appropriate to think it does. That’s fine by me as long as the art isn’t deemed as automatically superior to properly visual art, nor renders it irrelevant, as is so often the argument. We do, however, exist with the nearly ubiquitous conclusion that art which does not exercise the visual imagination of the artist or viewer is visually superior to art that does.

Again, reality is never in the thing, but only in the perception of the thing. Art manages to harness human awareness, intelligence, and imagination, manifest it – in the case of visual art this means in imagery – and make that accessible to another human being. The art which does this the most powerfully is more likely the art which brings us into contact with the real. I have to ask myself if the art which merely puts an inert piece of third rate contemporary archeology on a pedestal does that at all.

And if you are going to say that some art made you THINK, and gave you some THOUGHT, as if visualizing and imagining weren’t at least as complex thought processes as cerebral pseudo-philosophical questions to ponder over a latte, than please tell me that you value music for that same reason, and not for the experience of listening to it. Who, who is a genuine fan of music, values the quasi-philosophical ideas a piece presents more than the auditory experience of listening to music? And who prefers thinking about art to looking at it? Not the connoisseur of the visual imagination, or the profound and possibly unbounded realities is conveys.

Someone once said that if you think Duchamp is a philosophical giant on par with da Vinci, you must yourself be a philosophical gnat.

Brian goes on in his article to critique the critics and their verbiage, and it’s rather entertaining, but I was mostly interested in just addressing this question of what it real.

[The conceptual piece putting “The Fountain” back in the restroom is a (conceptual) prank by yours truly.]

~ Ends

Here’s a selection of some of my more imagination-based art, ‘ncase you were wondering:

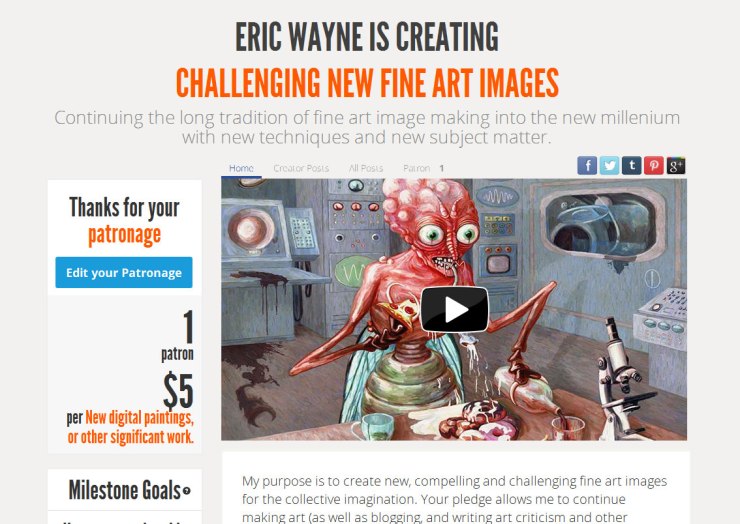

And if you like my art and art criticism, and would like to see me keep working, please consider making a very small donation. Through Patreon, you can give $1 (or more) per significant new work I produce, and cap it at a maximum of $1 a month. Ah, if only I could amass a few hundred dollars per month this way, I could focus entirely on my art. See how it works here.

Or go directly to my account.

Or you can make a small, one time donation to help me keep on making art and blogging (and restore my faith in humanity simultaneously).

Any advertising you see is outside of my control and I make no proceeds off of it.

Eric your article here is a very enjoyable bit of reading.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cool. If you put together a couple of my recent articles, plus one I’m writing now about “Art & Wonder”, I put togther the purpose of visual art, what is real in art, and that it should produce wonder. At least that’s one major ideal of art that is almost ocmpletely omitted. But, I’ll get back to that soon.

LikeLike