“Good artists copy, great artists steal.”

What does this maxim mean? Why do people like to repeat it now? Something smells fishy. People seem to think this is about taking shortcuts, but it’s nearly the antithesis.

The misinterpretation

This quote has become something so popular that people regurgitate it in conversations not even about art, which is how I originally heard it. My instant internal reaction was, “bullshit”. But, it seems both myself and many of those who actually like this quote got it wrong.

Without context, I fear the meme is so misleading as to be used to justify flagrantly ripping off other artists, mindless appropriation, and the self-defeating and false notion that originality and novelty are impossible. On the face of it, it seems to say that good artists imitate, but the greats fully plagiarize. There’s even a misquote of T.S. Eliot saying precisely that (from a 1949 article in The Atlantic): “T. S. Eliot once wrote that the immature poet imitates and the mature poet plagiarizes.”

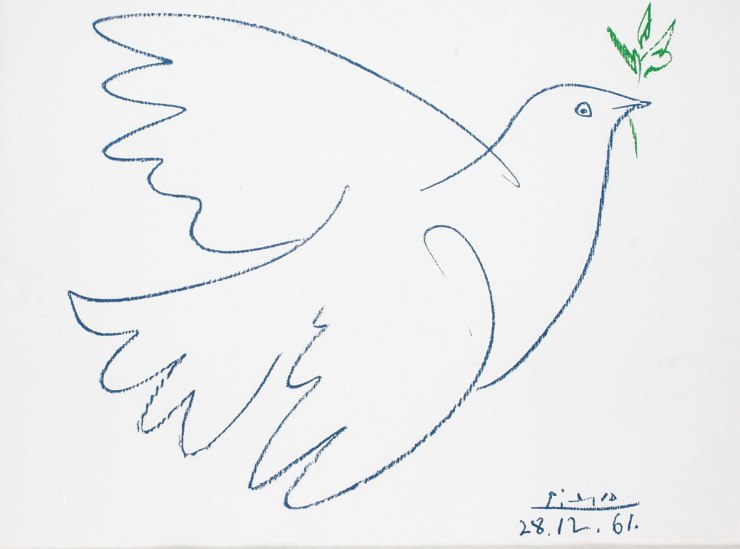

The maxim is most often attributed to Picasso, and thus functions to meld an artist popularly revered as a paragon of innovation with its opposite – merely stealing the work of others and taking all the credit for it. Note that Steve Jobs famously attributed the saying to Picasso, but Picasso is not famous for saying it, and many question whether he ever said it.

To get a fresh perspective, I asked my girlfriend what she thought the quote meant, and why people liked it. I’d already researched the quote, and had a good idea of what it meant in its historical context, so I was particularly interested in what impression someone got without knowing the real meaning. What she came up with substantiated my worst suspicions. Here are some bits I typed while she was talking:

“Nothing is sacred. Anything goes. Things like sampling in music. Taking something and making it your own. It’s a battle cry for entrepreneurs, because you don’t have to create anything on your own. Originality is dead. You don’t have to reinvent the wheel to make a lot of money, to get your name out there, be popular and well known. It’s being clever enough to see an opportunity where others didn’t. Not having to give credit.”

She really nailed it, and she also later guessed what the quote really means.

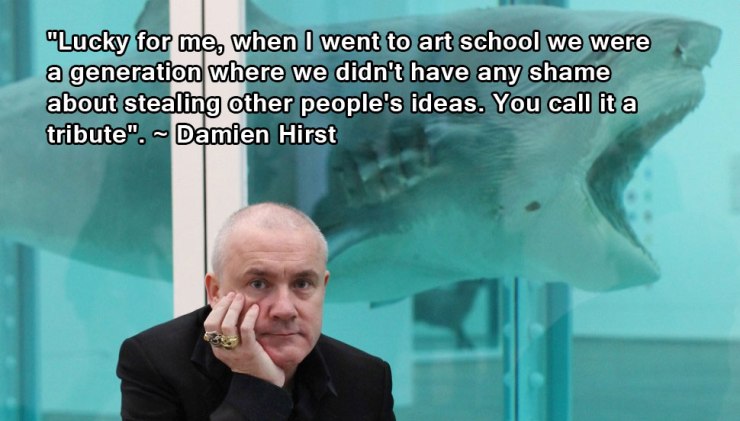

In short, the contemporary misreading is that savvy artists know what is good, don’t have a problem with a little cheating, and wisely take from others rather than innovate for themselves. They don’t even bother to learn how to imitate, but instead move directly to taking something outright, repackaging it, branding it with their own names, and marketing it. This is a common enough paradigm in contemporary art, and hence part of its appeal (the appropriation of Jeff Koons, Richard Prince, and Damien Hirst comes to mind…).

an internal flaw in the argument of the misinterpretation

If great artists steal, who the hell do they steal from? It can’t be from other great artists, who also steal. Do we steal from second and third rate artists? Or is there a time in the past when great artists were originators, and do we then just keep recycling their achievements? If that’s the case, at what point did great artists shift from originating to stealing?

It seems as though stealing is intended as requiring even less dedication than copying, but this is an inverse of the original meaning of the argument, which becomes obvious when we trace the quote back to its probable origins.

What did the maxim really mean?

This argument first appeared in 1892, in an article by W. H. Davenport Adams titled, “Imitators and Plagiarists”. The author was writing about Alfred Tennyson:

“great poets imitate and improve, whereas small ones steal and spoil.”

Not only does this earliest version of the meme mean the exact opposite of its latest incarnation, it also makes perfect sense. Here the bad poets merely steal something and fudge it a little to be their own, whereas the real poets learn from their predecessors and improve on the recipe. But have the words been switched around and the original meaning retained, or has the meaning been inverted as well?

Over 25 years later T.S. Eliot published “The Sacred Wood: Essays on Poetry and Criticism”, in which he wrote:

“One of the surest of tests is the way in which a poet borrows. Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different. The good poet welds his theft into a whole of feeling which is unique, utterly different from that from which it was torn; the bad poet throws it into something which has no cohesion. A good poet will usually borrow from authors remote in time, or alien in language, or diverse in interest.”

Here we see the words imitate and steal have switched, but the original meaning is intact.

| W. H. Davenport Adams | T.S Eliot |

| small [poets] steal and spoil | bad poets deface what they take |

| great poets imitate and improve | good poets make [what they take] into something better, or at least something different. |

Eliot’s further explanation couldn’t be more clear. The work of the good poet is completely different from the source from which it borrows, and integrated into a unique whole. This does not support the wholesale plagiarizing of someone else’s art, nor does it place the crafty opportunist who knows a good thing when he sees it, and how to re-brand it as his own, above the poet. The good poet needs to have the skill, breadth and scope to integrate inspirational sources into his or her own material. What is confusing people, I think, is the word steal. Eliot used it to mean a complete assimilation of a style into ones own art, but most people will generally think of plagiarism.

what did Picasso mean?

It’s still possible that Picasso could have meant something other than Eliot or Adams. There are two quotes that shed light on Picasso’s intent, assuming he really said them. According to Wikiquote, the statement “Good artists copy, great artists steal” comes from a 1989 article in InfoWorld, long after the artist died. The second quote comes from a 1965 article in Thought, and thus seems less arguably inauthentic:

“When there’s anything to steal, I steal”

Here I imagine an amoeba engulfing other protozoans.

Another possible way to say it is that in the search for truth, the seeker of truth will take clues from anywhere and everywhere. Or perhaps a martial arts analogy would work. In the Ultimate Fighting Championship, a fighter may have a deadly move that decisively wins a lot of bouts, such as when Ronda Rousey won nine matches in the first round with armbar submissions.

If you are going to fight in UFC, you would be wise to learn this move well, and how to defend against it. We could say you were stealing her move. Meanwhile she learned the armbar from her Judo instructor, who was himself a two-time Olympic bronze medal winner. In mixed martial arts, you can’t afford to give an opponent exclusive rights to a strike or maneuver. And so it came to pass, that, while Ronda had a deadly move up her proverbial sleeve, she also had an Achilles heel, which was her standing game. At the peak of her adulation and celebrity she suffered a devastating loss to veteran kickboxer, Holly Holm, when she was knocked out with a head kick.

This is an aside, but this defeat reminded me at the time how an athlete who was being heralded as the best pound for pound fighter in the world was utterly crushed by a bruising reality check outside of that belief bubble. A year later and Ronda got back in the ring for it to happen again, when Amanda Nunes knocked her out in the first minute with a volley of punches, which were perhaps more of a slap to the ego than hits in the head. Over-inflated artists, on the other hand, can bask in the self-delusional bubble of glory without an outside reality check for decades on end.

You can’t be a rarefied specialist in mixed martial arts. You can’t be like a Warhol who cornered fashionable surfaces absent of substance. You have to be well-rounded, and this might apply to the best artists as well, but don’t quote me on that.

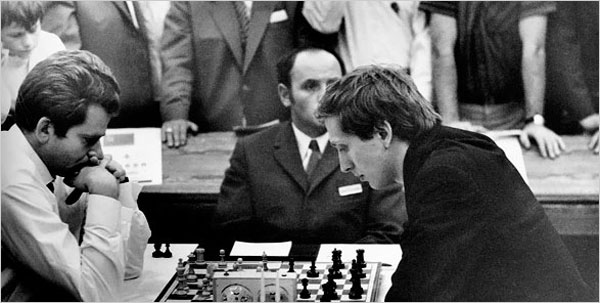

Even more obvious than MMA, in Chess, you must study, or steal the strategies of others and incorporate them into your game. You can’t just work on YOUR opening strategy.

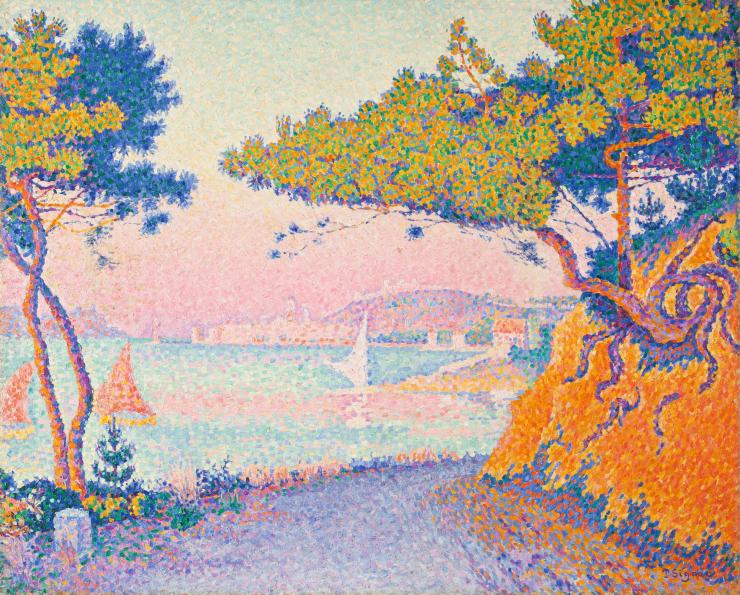

Often artists borrow from other artists, including their contemporaries, and it’s not a bad thing. The Impressionists and Post-Impressionists learned from one another. Paul Signac, for example, decided to become a painter when he was 18, after seeing an exhibit of the works of Monet, and his early works were in a decidedly Impressionist style.

After meeting Georges Seurat in 1884, Signac began to experiment with Pointillism and contributed to developing the style.

Related: See my “Van Gogh Self-Portrait With Cut Ear” tribute painting here.

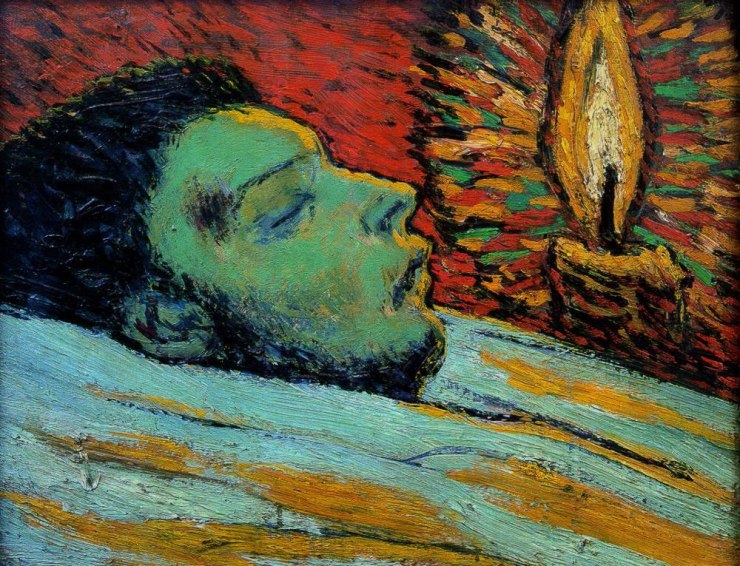

Picasso was, in turn, influenced by Van Gogh, and you can see his attempt at Vincent’s thick, directional brush strokes in his portrait of his friend who had committed suicide, Death of Casagemas, of 1901.

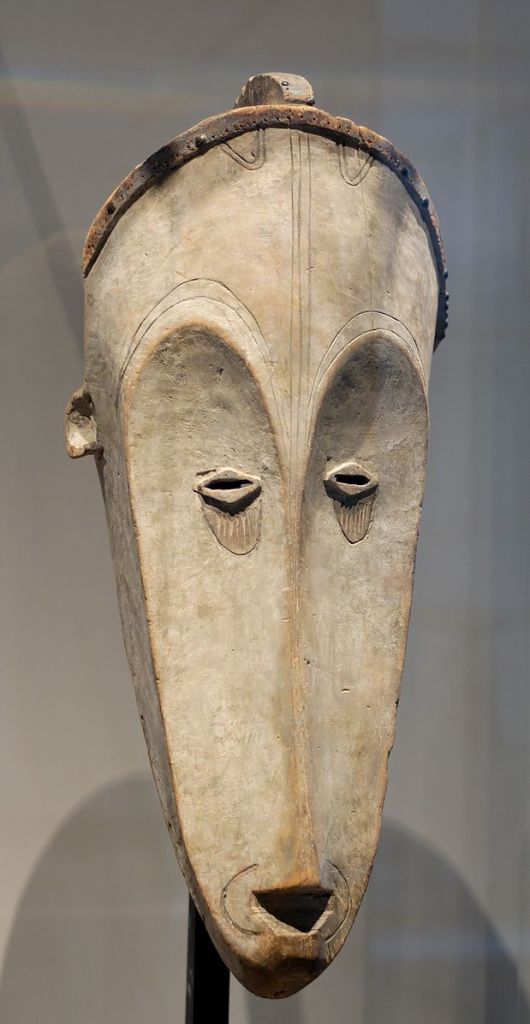

Early on Picasso notably borrowed from Toulouse-Lautrec, Gauguin and Van Gogh, then Iberian and African art …

I think in his use of African art, we can see what Picasso meant by stealing versus copying. Allegedly, Picasso had a revelation upon seeing the African art collection in a Parisian ethnographic museum, and was inspired with another avenue of taking painting away from traditional naturalism.

The good artist would merely make drawings or paintings OF the masks, or attempt to physically recreate them as they are. But the great artist, according to Picasso’s terms, would integrate what he’d learned into the fabric of his own creations, such as he did in his infamous Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

Picasso’s use of steal is consistent with Eliot’s, it’s the incorporating of another approach, or technique into ones own, and not merely aping the finished product, or repackaging it with a twist of lime. How well Picasso actually embodied the styles of Van Gogh or African art is another issue. Perhaps I should touch upon that.

Was Picasso a Great Thief?

For all his purported ground-breaking innovations, Picasso is an oddly limited artist. He died in 1973, which means that chronologically his life completely eclipsed some of the biggest art movements of the 20th century – including Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, Pop-Art, and Conceptual Art – but worked until the end as if they never happened. Not only did he never make a fully abstract image, his art revolved around some of the most conventional and even hackneyed subjects – self-portraiture, artist and model, still lifes, nudes, and mythological material.

While Picasso continued to work until his death, at 91, and even improved up until the end, he persisted with an early 1900’s paradigm. Georges Braque once said:

“Pablo? Oh, Pablo used to be a good painter; now he’s just a genius.”

This is a cutting comment, as it highlights the element in Picasso’s paintings that they are not so much great themselves as they are indicators of the greatness of their virtuoso creator.

Picasso was a bit like a kid whose doting parents tape his most careless scribbles on the refrigerator with excessive praise. He seems to have believed anything he tossed off was priceless, unalloyed brilliance. Paintings executed in an afternoon were exchanged for homes the rest of us spend lifetimes saving for. I suppose a more direct way of saying it is that a lot of his work is half-assed, and he didn’t feel he really had to push himself to get recognition. Picasso was the uber-genius long after the idea of “genius” fell out of favor and became a cringe-worthy sign of narcissistic immaturity.

Within his faith that he was the genius of the century, which allowed him to paint early 20th century art into the 1970s, he did do some marvelously eccentric things. And there is an alternative to the dangerous notion that one ism is replaced by another and rendered impotent in a linear development of art: artists express their own idiosyncratic individuality irrespective of trends happening around them. Picasso is an epitome of the latter, sheltered by his own fame, fortune, and “genius” to evolve in his own peculiar way, in an ivory tower. The risk of self-parody and inbrededness aside, it may be better to be relatively oblivious to successive waves of evolving trends than to be permanently sandwiched in one. [A bit of a tangent, but I wonder whether the premature deaths of Rothko and Pollock might have something to do with working in styles which were linked to an ism which had been superseded by successive waves of isms in which case the artists become antiquated along with their styles.]

Below, in his late years, Picasso’s paintings became more loose, brushy, and expressive, even if an arcane stylization of his personal iconography. As original as this art is, it’s strange to think it was painted eight years after Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans. That, however, does not take away from it, and I prefer this painting to most his Analytical Cubist work, which I find a bit too nauseatingly green and orange and angular. His vision matured and distilled, whether or not it did so in concurrence with wide-sweeping, popular, artistic movements.

Can Picasso really have absorbed African art into the broader scope of his own artistic practice, or, is it much more likely that he could hardly fathom what African masks meant to the culture in which they were created? His assimilation of Van Gogh was merely thick brushstrokes with primary colors, but without Van Gogh’s orientation to color (Picasso was never as good of a colorist as Van Gogh), or the intention behind his directional brush strokes.

Picasso’s quote was, I dare say, bluster from an over-inflated ego that even he didn’t live up to, let alone those who glibly quote him in order to glorify pilfering from the hard-won originality of others.

Why is this misinterpreted quote so popular now?

Today stealing from other artists, musicians or writers is easier than ever. It’s as simple as ctrl+c, ctrl+v. When everyone can be an art thief, everyone has an interest in doing so being justified by artists themselves. If Picasso says stealing is what great artists do, than we can all feel good about stealing from other artists, including Picasso. In design, if you like a website, or some packaging, just copy it outright and put your own logo on it. Call it a day. Congratulate yourself as being better than the person you copied from, because more savvy. If you have a better marketing strategy, or more money to throw at promotion, than you can assure yourself that marketing strategies are art, and making money is art. You can find quotes from Warhol and others to support these further conclusions.

Of course, some may use the quote today to mean it exactly as intended, to learn from other creators and integrate it with your own vision into a unique whole, which is sound advice. You don’t have to reinvent the wheel.

The quote can also be used to substantiate common contemporary art practices such as appropriation, some of which is valid (David Salle, James Rosenquist, Ed Ruscha, Claes Oldenburg, Glenn Brown, John Baledessari …) and some that goes too far (Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, and Richard Prince). Koons, Hirst, and Prince have all been sued for plagiarism more than once, with Hirst in the lead, having eight cases against him. The paradigm in which the great artist literally steals substantiates the practices of these latter appropriationists. Let’s take a look at some of their excesses, and why we might not want to underpin their production with the quote from Picasso.

Bad artists copy, jeff koons steals

Koons has stolen from his contemporaries, but I’d like to focus on his theft from old masters. In a recent series he selected great paintings from art history, and had his assistants make larger-than-life copies of them using a tedious paint-by-number system (making them into human oil paint printers). He then affixed his trademark shiny blue gazing ball on the paintings, thus, by his logic, improving upon them.

Above we have a very literal copy of Manet’s classic painting. Surely, Koons’ assistants’ reproduction doesn’t compare with the original, in which case the ball alone is supposed to transform it into something better. And the same damned ball, in the same color, and in the vertical center is supposed to improve each painting. This isn’t the mastering and assimilating past styles into ones own that Eliot recommended. These paintings trivialize the original works and bottom out their mystery. The gold leaf in a Klimt painting – one of his peculiar contributions – is replaced with mere gold paint.

Koons wants to accrue to himself the skill and vision of these past great painters, thus making himself an all-time great painter in the bargain. He even asserts that he improved upon the original paintings:

“These paintings are stronger being together with the gazing ball. If you take away the gazing ball, they don’t have the same power. They don’t have the same phenomenology taking place. These paintings are masterpieces in their own time, but in this time, this moment, they’re most powerful in this state, with this gazing ball.”

Most would never presume to improve on a “masterpiece”, but, Koons can kick it up to eleven. Koons literally stole completed artworks, in their entirely, branded them with his trademark, and then presumed to somehow make them even better, and take credit for them.

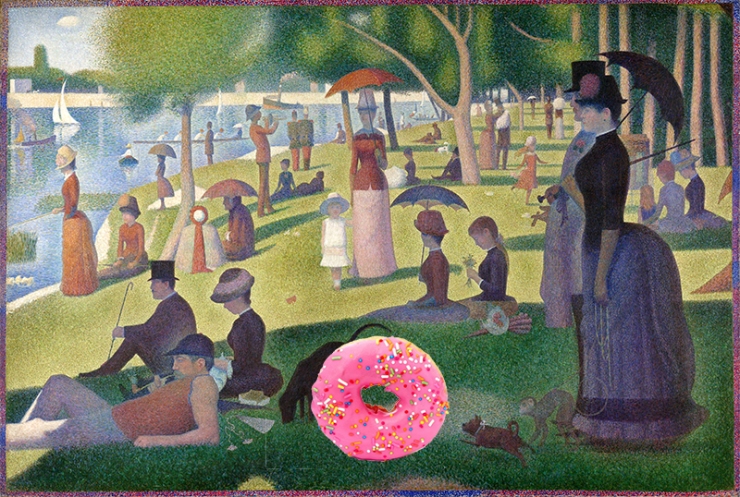

You can’t improve on the Mona Lisa, Jeff, but I had a better idea of how to have fun with them. If we are going to attach a 3D object front and center, how about a ceramic doughnut? You could choose the type of doughnut in accordance with the painting, and serve donuts at the exhibit, for free.

Behold!

bad artists are imitators, bad boys are fooking parasites

Damien Hirst is like the schoolyard bully of the contemporary art world, beating up even his friends for their lunch-money. Hirst has lifted ideas from friends and other artists, branded them as his own, inflated their scale and price, and given the original artists the finger. The saddest part isn’t that someday his ego may hit the canvas harder than Ronda Rousey after Holly Holm kicked her in the head, but that those other artists’ careers were destroyed in the process. They can’t exhibit their own work because it’s rejected as too derivative of works which made Damien Hirst internationally famous. Man that’s gotta’ burn, sinking in ignominy because someone else got rich and famous of your own achievement first.

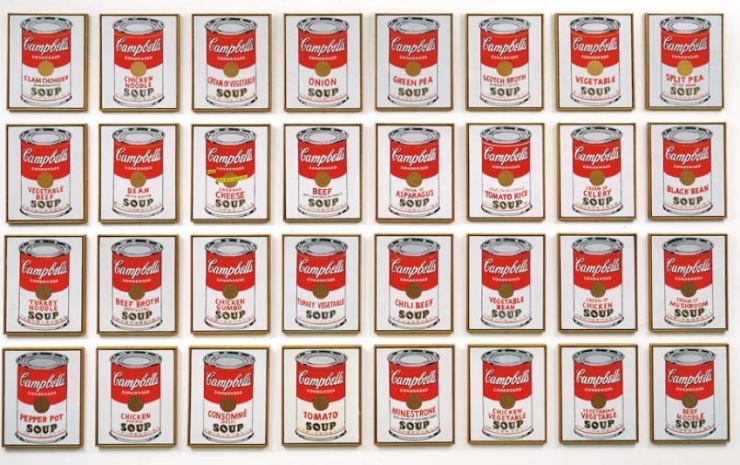

Both Koons and Hirst operate as CEOs of art factories, à la the mature and jaded Warhol. And I’ll just mention that Andy painted those 32 soup cans himself (albeit using a non-painterly printing method), and that made them all the better, even if the piece was obviously more about the idea than the execution.

Sure, it’s a 32-line one-liner, but clever, and fresh. And there is a performance element of him going through the repetition of painting each nearly identical can, even if it was just the flavors. Ironically, when you pay someone else to do your art for you, as he later did, and Koons and Hirst routinely do, it cheapens it, sorta’ like when pop stars like Madonna or Britney Spears lip-sync live concerts.

Hirst is like a rich CEO in an ideal dream world where there are no applicable patents. In the art world you can’t steal the final manifestation of a work, but you can steal the idea behind it. This is Hirst’s key to success, but why oh why did he not just hire people to come up with ideas for him as well?

Hirst was friends with conceptual artist John Le Kay, visited his studio, drank with him, went to art openings and shows with him, and played badminton in his living room with a basketball. It’s safe to say Damien saw John’s work. Later, Damien produced several pieces closely resembling his work, including a crucified sheep.

LeKay had this to say about it:

“Damien sees an idea, tweaks it a little bit, tries to make it more commercial. He’s not like an artist inspired by looking inwards. He looks for ideas from other people. It’s superficial. Put both [crucified sheep] together and … it’s the same thing.”

While LeKay has sold nothing for more than £3,500, and can’t live off of his art, Hirst’s sheep, of which he made three, sold for £5.7 million.

LeKay made a series of skulls out of various shiny materials, including cheap Swarovski crystals. Hirst’s most financially ambitious project was a platinum covered human skull covered with 8,601 flawless diamonds, including an enormous pink diamond on the forehead. He hired the jewelers Bentley and Skinner, who had an appointment to the Queen, to create it for him.

When Hist produced his skull, For the Love of God in 2007, LeKay received a phone call from a friend, who advised him:

“You won’t believe what Damien has done, he is doing a skull covered in diamonds. It looks just like your work and he is selling it for 100 million dollars.”

LeKay has subsequently articulated his feeling at the time:

“At first I thought it might be some kind of a joke, and I laughed, then I read about it on artnet. I remember feeling these mixed emotions, feeling a bit shocked, but simultaneously flattered by it, then a bit gutted and thought here we go again, even though his was different; different materials etc. I mean diamonds are much more expensive crystals than a urinal cake or Swarovski crystals, but the idea was basically the same. A skull covered with crystals.”

LeKay claims it has become impossible to show his own work, “Because now everyone who sees it now says it looks like a Damien Hirst artwork”.

There are a few other of Hirst’s pieces which remarkably resemble LeKay’s prior works, and a total of 15 pieces that are contested as entirely derivative of other contemporary artists’ work. These include the shark tank, the spin paintings, the dot paintings, the pharmacy cabinets, the butterfly kaleidoscope paintings, and the diamond encrusted skull. That doesn’t leave much to be potentially original.

Of the contested works I’ve seen, I’d have to say that Damien improved upon all of them, at least in the sense of viable contemporary art objects with WOW factor. And there’s something to be said for improving something, even if it’s largely due to how much money one can throw at it, and who one can get to produce it for you.

Even if Hirst improved upon other artist’s work by super-sizing it (if that really improves it), he still couldn’t have done it if they hadn’t made their pieces first. Consider how this works with popular songs.

In an interview in 2009, Hirst boasted:

“I’ve always thought that art and crime are very closely related. Crime is incredibly creative. There’s the bank. If I buy that site next to the bank, I can dig a tunnel, break up the floor, take the money out, go back through the tunnel, and no one would know I was there. That is exactly what art is like.”

I wonder how many, or how very few, believe this is what art is like. In fact, such a notion has never occurred to me. I’m much more with LeKay on this one, and believe tapping ones inner resources is the ticket, not pilfering ideas off of others who don’t have the means to commercialize and super-size them [which I couldn’t do anyway]. This brings me back to the fallacy of the misinterpretation of the quote: if there were no LeKays, there’d be no Hirsts, but if there were no Hirsts, there’d still be LeKays. Though, admittedly, Hirst could just be making an analogy between the creativity of crime and that of art, and not alluding to crime being his art.

For more background on Hirst’s plagiarism, Charles Thomson – co-founder of the Stuckist movement (ironically named after Tracey Emin accused one of them of being “stuck” in painting) – is the outspoken source of the research and argument. Here are his two definitive articles on the topic:

1. Stuck Inn XI: The Art Damien Hirst Stole

2. Stuck Inn XII: The Art Damien Hirst Stole Part 2

Linking Hirst to Picasso, and the art Picasso “stole”

More pertinent to this article is the counter to such accusations against Hirst, which use the Picasso quote to defend him. I’m quoting a few paragraphs, because he articulates precisely the position I am arguing against. In response to LeKay’s complaints, Ben East wrote in TheNational:

Does it really matter? As much as one can feel sorry for LeKay, struggling in the cultural margins while his sometime friend is banking millions, it’s hardly new for a famous artist, musician or writer to be accused of such behaviour. As LeKay admits himself, the very reason these people are rich, successful and talented is often because they take the nub of an idea and hone it into something that has mass appeal. In that sense, Hirst’s use of the Humbrol toy isn’t so far removed from Warhol’s famous soup can images – and no one’s suggesting they’re not interesting, original art, even though controversy has circulated around the provenance of Warhol’s work too.

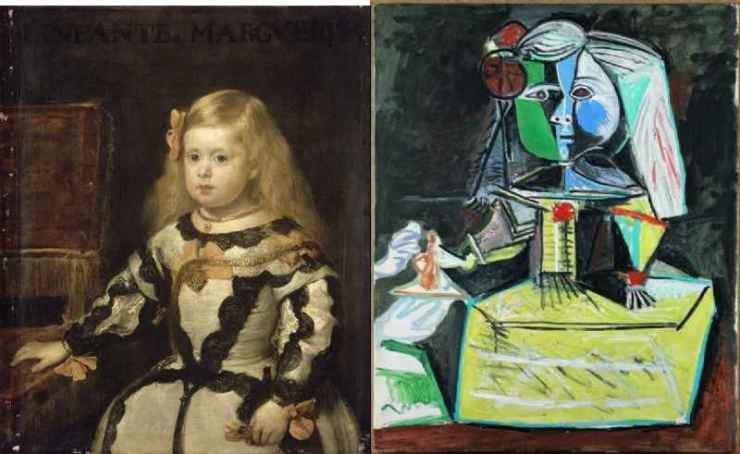

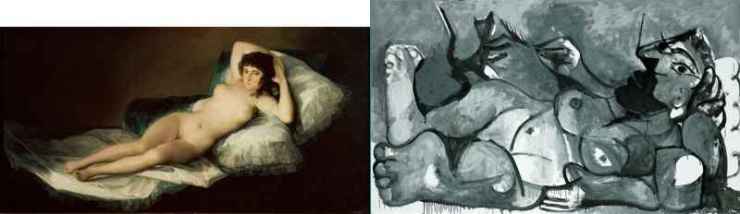

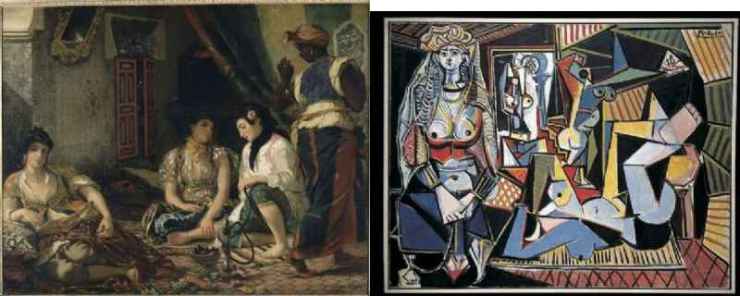

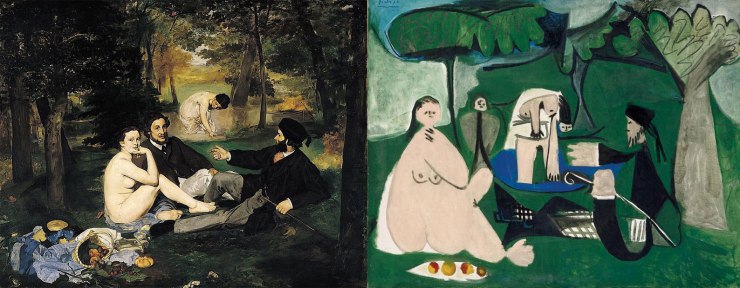

A sense of timing is also important: Hirst revealed For the Love of God to the world at the very moment vapid celebrity culture was at its height. Thirteen years earlier, when LeKay was sticking jewels on skulls, we were in the middle of grunge. In the art world it’s rare to find work not influenced by anything that has gone before it. Even Picasso wasn’t afraid of copying his favourites. A whole chapter of the Spanish painter’s career features “stolen” images, in his case not from unknowns but from great masters such as Velázquez, Goya, Manet and Delacroix. But in every instance he added something new and intriguing to the original, and in the process offered a great quote: “Bad artists copy. Good artists steal.”

The iconic pop artist Roy Lichtenstein probably empathised: he appropriated whole images from DC Comics’ storylines, but by increasing their scale and changing their details, he changed their meaning and in so doing made some of the best work of the 1960s. Appropriation is a fully recognised artistic tradition stretching right back to Leonardo da Vinci, through Picasso, Duchamp and Warhol, although the protocol is that the source of inspiration is named.

Ben East’s argument is worth dismantling. First he argues that it’s not unusual for a famous artist to be accused of plagiarism. Ah, but it is rare to be accused on 15 separate accounts [16 including a more recent one], spanning ones most famous works, to have been sued eight times for it, and successfully at least once. He continues that it’s rare to find anything in the art world not influenced by something else. I agree, but being influenced by something, and taking something outright are nearly opposite things.

We next learn that Hirst’s skull was successful because he made it during the “height of vapidity”, whereas LeKay poorly timed his pieces during “the middle of grunge”. Is he talking about “grunge” music, as in Nirvana? I think he is, but this doesn’t make sense. Were Nirvana’s audience the same people buying multi-million dollar pieces of art, and was the art world influenced significantly by the alternative rock genre? And let me get this straight, skulls were unpopular with grunge artists?! And while Hirst has asserted “For the Love of God” was about death we should accept that death is what appealed to the vapid? And even if Hirst’s jewel-encrusted skull did attract the vapid, is that an argument in defense of his art?

Next, East compares Hirst to Picasso, asserting Picasso “stole” images from the great masters. This is far more persuasive if one is just playing around with arguments and doesn’t know what the Picassos in question look like.

There are more, but you get the idea. All of them are unmistakably mature Picasso works, painted by his own hand, in his distinct style. In Hirst’s case his versions of other artists’ work are so similar that they can’t sell their own work anymore, and he doesn’t create it, nor is there a personal style, as it’s all deliberately impersonal.

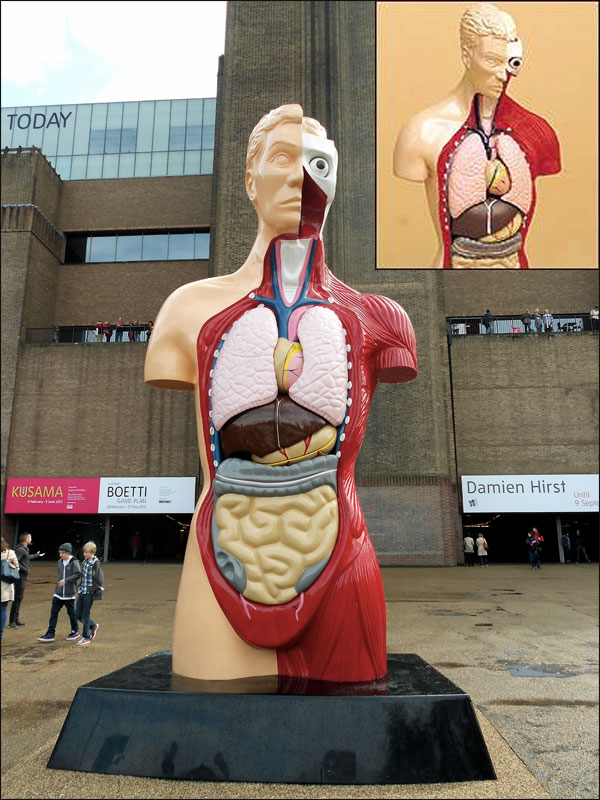

East goes on to assert, “Hirst’s use of the Humbrol toy isn’t so far removed from Warhol’s famous soup can images”. Au contraire, Hirst’s “Hymn” is a giant sculptural copy of a small sculpture, and that’s about it.

Warhol made rows of paintings of cans, tilted at an angle toward the viewer, transferring the 3d into flat 2d design, and his painting them all is akin to his drinking those same soups, exploring the different flavors. There’s an element of process to the “Campbell’s Soup Cans” that is absolutely missing in Hirt’s giant copy of a toy, which he had manufactured for him by others. Warhol’s paintings obviously announce their source, while Hirst hides his. I’m not a Warhol fan, because, well, I prefer more deep, gripping, emotional, transcendent, or transportive sorts of things, and he’s thin gruel, but, he’s witty, and the soup cans are charming. If I were lobotomized I can imagine doing something like that myself. That’s a bit harsh, but after a few decades of familiarity with Warhol’s oeuvre, it just attenuates into substancelessness. Hirst’s dark sensibility is a bit closer to mine, but I think Andy was doing a lot more with a lot less, and over 30 years prior. And if it is the concept we are most focused on, Hirst’s “Hymn” doesn’t say anything that Warhol’s “Brillo boxes” didn’t say.

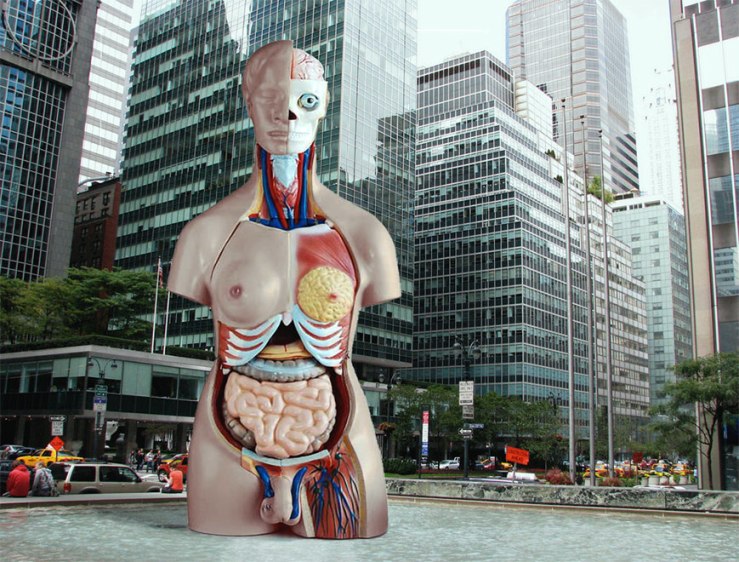

I think Hirst could have gone further and used an androgynous toy anatomical model, y’know, for shock value. I created this in Photoshop as part of a prank, a while back, to illustrate some related points.

Hirst’s “Hymn” is just the same idea of making a large copy of a utilitarian object, and putting in a museum context. Same thing he usually does. Same thing Koons usually does. And we don’t question whether making extraordinarily expensive objects for the gallery space is not a sign of being “radical” but rather of being conventional. We don’t need Jeff Koons to figure out that a Lay’s potato chip bag would make an awesome polished chrome appropriation in 2017. We can figure it out for ourselves. Here, imagine this as a giant Koons, with a bend in it, propped up against the side of the blue chip, white-walled gallery:

A candy wrapper would also make a great Koons. Here’s another faux-original courtesy of my Photoshop skills.

Next, East offers us up this savory tidbit:

A whole chapter of the Spanish painter’s career features “stolen” images, in his case not from unknowns but from great masters such as Velázquez, Goya, Manet and Delacroix.

There’s a lack of hard evidence that Picasso ever said this, nor that he made that quote in reference to that body of work. But if he did, to “steal” was to wholly transmogrify the original into ones own peculiar style (which, by the way, can’t be a style of mass production, which is not ones own). But notice that East acknowledged Picasso used art from “great masters”, not lesser known contemporaries, in which case the sources were already known, and the artists dead.

East concludes with a bizarre anachronism that should stop most people who have studied art history in their tracks:

Appropriation is a fully recognised artistic tradition stretching right back to Leonardo da Vinci, through Picasso, Duchamp and Warhol, although the protocol is that the source of inspiration is named.

What? Appropriation started with da Vinci, and then the baton was carried on by Picasso, Duchamp, Warhol, and finally Hirst?! I don’t believe that is true at all. “Appropriation” was started by the likes of Picasso, Braque and Duchamp in the 20th century, and specifically means incorporating into ones art something that is recognizable as an unaltered outside source. Picasso and Braque included pieces of cardboard, wall-paper, newspaper, and other crap into arguably some of the their most dreary and uninspired works, though they have some historical significance, to be sure. Duchamp hauled a urinal into a gallery and called it art (and it is now worshiped as the holy grail). That’s when it started. I mean, c’mon, da Vinci?! He wasn’t an original, but merely an appropriationist borrowing popular art and re-contextualizing it as fine art in the gallery? OK.

When Beethoven was influenced by Mozart (or Mozart influenced by Haydn), that wasn’t “appropriation”, that was the kind of stealing T.S. Eliot was talking about. Beethoven didn’t just play one of Mozart’s piano sonatas and boldly declare, “I am playing this in a new context, and am the author within the new context, in which the piece in question is not the music per se, but rather the act of my playing it, thus challenging notions of what is and is not music”.

Da Vinci is not an appropriationist. Gimmie a break. And neither is Picasso, really, other than when he incorporates odd materials, but even then it’s not the kind of appropriation that today’s leading conceptual artists look back to as influential. They go to the master of conceptual art mind games, and breezy one-upmanship, Marcel Duchamp, and it’s worth noting that Duchamp and Picasso were well known rivals occupying opposite camps. When Duchamp died, Picasso famously opined, “he was wrong”. What he was wrong about, according to Picasso’s vantage, was art, and I’m assuming particularly his notion that painting was washed up. Consider what Picasso said in his last recorded words.

other more telling quotes by Picasso

Picasso’s famous last words, so to speak, were:

Painting remains to be invented

Oddly we do not quote his last recorded words, but rather something which there’s no concrete documentation of, and which is taken out of context. And what did he mean? The wording is a little odd to me. He can’t mean that painting hasn’t been invented yet, which is what it literally says. I interpret it to mean that painting still exists (remains) to be developed (invented). Painting had not died with the arrival of Duchamp’s urinal, as many a critic has argued, but was there just waiting for someone to come along and bring it back to life. I think it’s safe to say he didn’t mean by appropriating prior works, ironically, in order to challenge their originality, and so on.

There’s another quote that I think one of my drawing instructors told me back in the day:

“You must always try to imitate someone else, but the fact is you can’t. You would like to, you try, but you make a botch of the whole thing. And it’s at that point, when you make a botch of the whole thing, that you are yourself.”

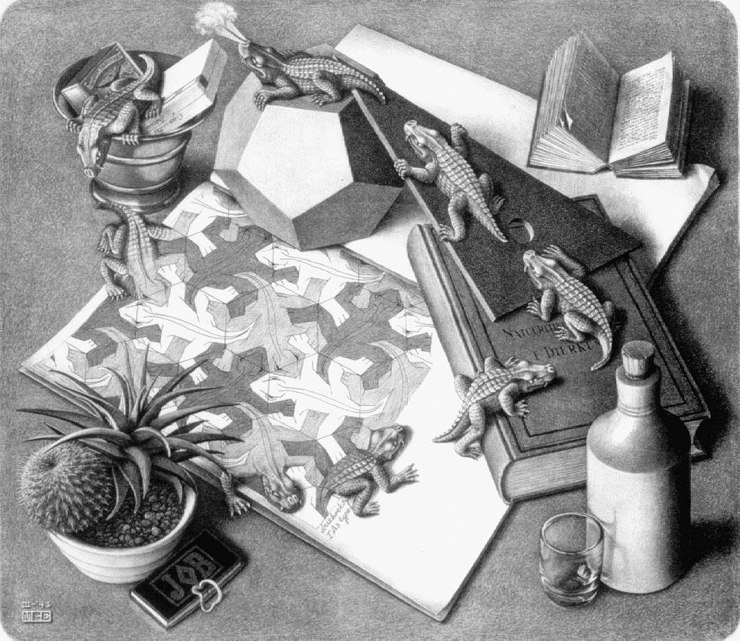

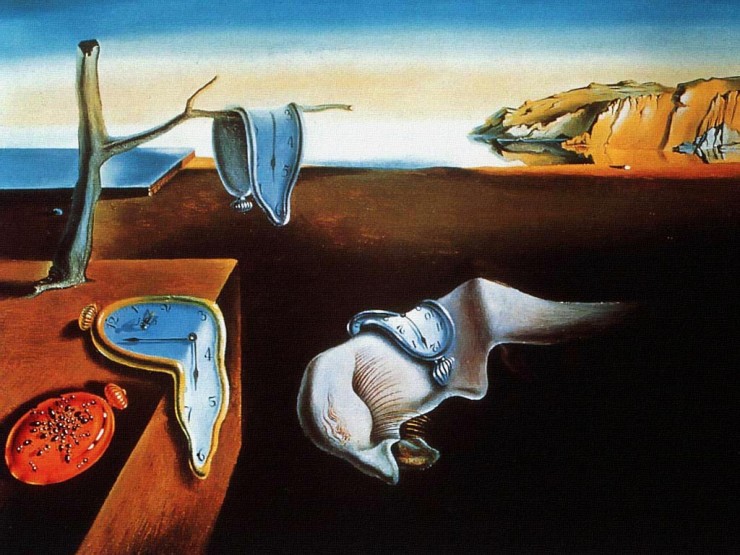

At this point, I’m going to switch up my tactic and try to not use argument to make my point. I’m going to do it with a simple graphic. The following is precisely what Picasso meant by “stealing”.

Why painting and originality are not dead

The simplest argument in defense of originality is, “when was the cut-off point?” I like to elaborate that, as a species, either we were always capable of originality, or we never were. By original we don’t mean that someone created something out of nothing with no prior influences. Anyone who has had an art history course knows artists stand on the shoulder of those that went before. However, in order to integrate that knowledge and background into something new, you have to add the new part, which is your own vantage point, based on your own unique experiences, education, and training…

Oddly, countless articles which deny originality also laud their chosen artists as “radical”. By me, “radical” is more original than “original”. “Radical” is a complete departure from the past, and has someplace new to go. How can that new place NOT be original, if it is a breach from the past?

Similarly we will hear that the artistic “genius” is a thing of the past (I don’t like the idea of “genius” either, as if some people are inherently superior to others), but then we credit artists such as Duchamp with super-genius powers, such as that he could check-mate all previous art styles in one sweeping gesture.

But if we consider “original” to mean what it meant in visual art before, there’s no reason it can’t continue. We have access to media that never existed before, and even experiences. There’s no reason an artist can’t build on what went before, add to it, and create a new recipe or two or three.

As for painting, I use “painting” loosely here to mean “visual images”. And my most succinct argument to defend visual image art as not dead is to simply give the option that it should be, in which case there wouldn’t be any more new visual images. That is as appealing as not having any more new songs.

But let me take another tactic. Here are a few examples of largely original art pieces from the 20th century, after visual art was declared moribund, and nothing new could be done.

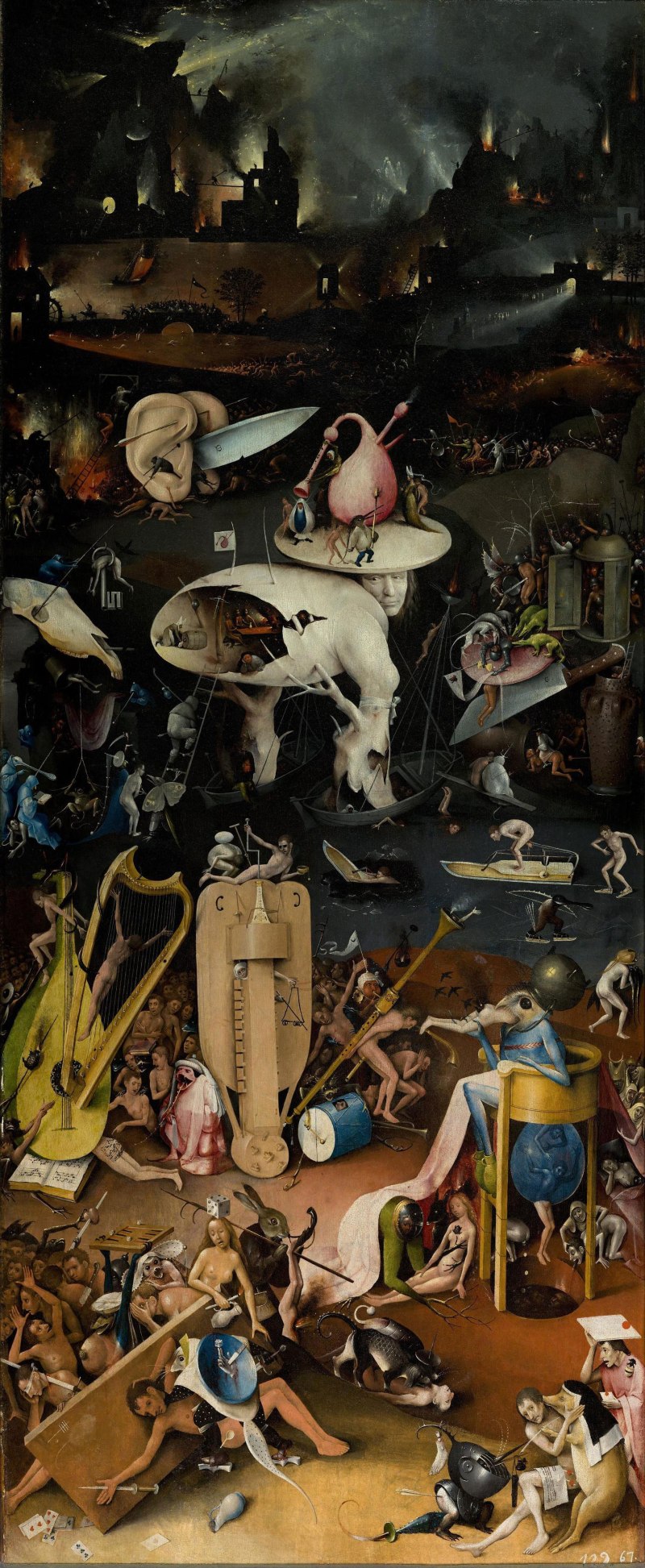

Whether you like these artists or not (only Bacon is in my present personal Pantheon), it’s easy to see that if they hadn’t come along and made these images, nothing like them would otherwise exist. Imagine a world without the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch.

There always has been originality in visual image art, and there always will be. Why people convinced themselves this was impossible, or undesirable, I can’t quite fathom, or it’s too stultifying for me to want to. I also don’t believe it’s all that hard to add something to the pre-existing mix, but rather think, like Picasso, it might be an inevitability if one persists long enough, and even if one is trying to copy the art of someone else.

“Stealing”, in the traditional art sense, means wholly digesting and incorporating into oneself. It does not mean appropriating whole objects and re-contextualizing them as art, or pilfering the ideas of lesser known artists and marketing them with ones own recognized brand. It doesn’t mean appropriation at all. For that I’m sure there are ample quotes by Duchamp and Warhol. But you can’t use Picasso as an example of that which is entirely antithetical to his art and process.

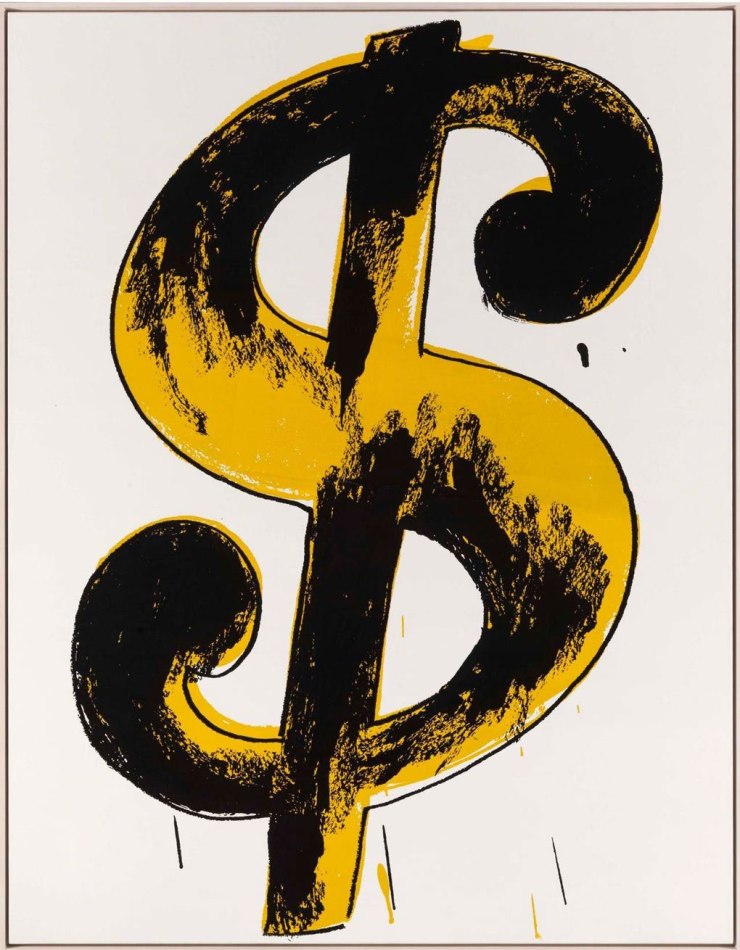

What you are probably looking for, then, is this gem by Warhol:

Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art. Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.

Please excuse me while I go vomit.

It wasn’t you, good reader, it was the Warhol quote.

Addendum:

Apparently the quote by Warhol is a favorite of Donald Trump, and he’s quoted it several times, and in two of his books. Here’s a couple instances from Think Like a Champion, of 2009.

“There’s a certain amount of bravado in what I do these days, and part of that bravado is to make it look easy. That’s why I’ve often referred to business as being an art. I’ve always liked Andy Warhol’s statement that, ‘making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.’ I agree.” (Think Like a Champion, page 57)

“We are all businessmen and women, whether you see it that way yet or not. If you like art and can’t make money at it, you eventually realize that everything is business, even your art. That’s why I like Warhol’s statement about good business being the best art. It’s a fact. That’s also another reason I see my business as an art and so I work at it passionately.” (Think Like a Champion, page 86)

~ Ends

And if you like my art and art criticism, and would like to see me keep working, please consider making a very small donation. Through Patreon, you can give $1 (or more) per significant new work I produce, and cap it at a maximum of $1 a month. Ah, if only I could amass a few hundred dollars per month this way, I could focus entirely on my art. See how it works here.

Or go directly to my account.

Or you can make a small, one time donation to help me keep on making art and blogging (and restore my faith in humanity simultaneously).

Well, I was going to visit the East Building at the National Gallery of Art here in Washington, DC, today, but a bad sprain kept me at home. Instead, happily, I encountered Mr. Wayne’s superbly entertaining and illuminating reflections of the notions of originality and its galaxy of ideas. With his generous and magisterially selected illustrations, Mr. Wayne’s article is nothing less than a brilliantly argued defense of art itself, simultaneously honoring the work of Sir Philip Sidney, T.S. Eliot, and Robert Hughes — to say nothing of the visual artists Mr. Wayne so vividly and shrewdly invokes. What a rewarding and pleasing read! And when I do make my next visit to the NGA, I shall enjoy its treasures with fresh eyes!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks! Hope your sprain heals up quickly. Ah, I didn’t mention Hughes, but as he’s my favorite critic (they really don’t make them like that anymore) his influence undoubtedly is present. Hughes on Warhol, Hirst, or Koons is so rough it’s funny. For a lot of people Hughes is a pretentious Australian dinosaur, but that’s what’s also great about him.

Thanks for your comment and for reading the piece.

LikeLike

Eric,

You do hear that quote a lot these days, and it is taken the way your girlfriend originally stated. It definitely is more difficult to paint something now that doesn’t look a little like something someone else did than it was just 80 years ago. That doesn’t make what Hirst does ok in any rational persons mind. He doesn’t care because he knows he’s not an artist. Or maybe it bothers him deep down, but he seems just fine to have fooled enough people into spending sh:t loads of money on stuff other people came up with and made for him. That doesn’t bother me because the people who pay for it don’t care if it actually came out of his butt as long as they can sell it for more than they paid for it. They don’t buy art, they make investments. Probably a good time to sell short if your in that market, but If you actually want to buy some good art you can find lots of it for a few hundred dollars. Just go with your gut when buying art. Back to Picasso. I’m not sure of Picasso’s meaning your probably right but something about his story has always bothered me. When he was 12 his father who was an art teacher and that’s how he made his living gave up painting because his son had surpassed him. Now it’s hard to find many paintings by the older Ruiz but the ones you can find look a lot like the young “genius”. Sounds a little like the story of the young Australian girl who paints abstract expressionist paintings who’s parents just happen to be abstract expressionists. Also the story goes that he could do the human form perfectly at a young age but I’ve only seen one where he did the hands and feet very well and it was when he was 14 of the barefoot girl. At some point Picasso stopped signing his painting with his fathers name and changed his painting style completely. That took courage. He went on to do some creative stuff but maybe he was always pushing the limit of plagiarism himself.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Matt: I think you may be right about Picasso. He boasted repeatedly about being able to paint like Raphael as a teenager, and there’s no evidence of it I’ve seen other than some carefully copied plaster casts that most artists of the time practiced with.

Hey, did you read about the little girl genius with Abstract Expressionist parents on my blog? I wrote a long article about it.

I’ve never really gotten that into Picasso. His arrogance and narcissism are insufferable. As I said in the article, his paintings are less great than physical evidence of his virtuoso greatness.

I had one teacher who loved Picasso, though. So I gave me a chance, bought a massive book, and poured over it. There are a dozen or so pictures that I think are really good.

I’m actually toying with doing a Picasso influenced piece (right now I’m doing a “cover”, so to speak, of a Nolde painting). The reason is he has a contribution that’s rather interesting, and which obviously appealed to George Condo – he creates imagery without obeying any of the laws of naturalism.

Right now I struggle with trying own lighting, shading, modeling and perspective. Those are tough things to do when you aren’t copying something (in which you can just copy what you see), but work from the imagination. But what Picasso did was the opposite. You construct an image without following any of those things. You just use line and color. Trying this could be as useful an exercise as doing a photorealist painting, or an abstract painting. Then, of course, the idea for me is to integrate those elements into something new.

Based one your input, I rather do think Picasso’s father was very important, and without even going into conspiracy (so to speak), he gave Picasso a headstart that few artists had (access to materials and a dedicated teacher), in which case what appears to be extreme precociousness is actually just good early training.

I really don’t like the “prodigy” idea, because it presumes that some people are inherently different, born artists. I made art since I started walking, but that’s because my Mom liked art. I remember her showing me how she colored in a coloring book by using swirls.

Also, I like what George Condo does with Picasso better than most Picassos.

Thanks again for reading and writing. I really appreciate my repeat “followers” (there’s gotta’ be a better word), um, correspondents? Participants in an ongoing dialogue? And your input helps me round out my understanding. Cheers.

LikeLike

– – – To Eric Wayne – Hello from Chattanooga, TN . This is a great article, but I had to stop about 1/3 of the way through due to personal duties before a snowstorm hits our area. You’re a very good writer, and i look forward to relaxing tonight and finishing it. I took the liberty of forwarding your email to my daughter – Dorothy Jean Mussared, who is an artist that always appreciates good ‘stuff’ from the real world of art. I will make a public comment on your site and probably on the Social sites also. Best Regards, JMD

On Thu, Jan 5, 2017 at 3:29 PM, Art & criticism by eric wayne wrote:

> Eric Wayne posted: ” “Good artists copy, great artists steal.” What does > this maxim mean? Why do people like to repeat it now? Something smells > fishy. People seem to think this is about taking shortcuts, but it’s nearly > the antithesis. The misinterpretation This qu” >

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi John. Well, I hope you like the rest of the article when you get around to finishing it. I always worry some of my opinions or turns of phrase may be a bit too colorful or outlandish. However, I do find that entertaining in others’ writing. Thanks for your comment and support!

LikeLike

Eric,

I did read about the little abstract expressionist girl on your blog. I agree with you that Picasso’s father was a big influence on his work. Possibly overbearing like the girls parents. But I can think of worse things for a young kid than parents who get you into art. I am in total agreement with you on the prodigy thing. How do you really determine if someone is a prodigy? If I were determining who was a child prodigy it would probably be the ones who go outside the lines who were the prodigies. It doesn’t really matter. What matters is if you love painting you will stick with it, and he did. I like his blue and rose periods best but they aren’t revolutionary. I also like the abstract stuff, but can do w/o cubism.

I love Nolde, I didn’t think he was very well known because of his love of the nazis. Glad you do too. I think he was one of the best colorists of all time.

I don’t do much shading in my work, so I prpbably won’t be much help to you with that. If I do I usually try to set up a light and take pictures of things or people to help me along. I change colors a lot very subtly so it give the appearance of movement. I’ll use 4 or 5 blues in an area that are not very different so most people don’t notice it much but it definitely gives the painting life.

I don’t know George Condo so I’ll check him out. Still haven’t read Ayn Rand yet. Got going on a bunch of paintings of Sisyphus and it’s been taking up a lot of my time.

One other thing I wanted to mention since you’ve been all over Southeast Asia. I saw this documentary last week on elephants painting and thought it was so amazing. Then they showed how they take them from their mothers when they are young and break them and force them to paint. Half of them die in the process. They are scared for their lives every day. I thought people should know so if they go there they don’t buy any of the paintings and promote this. Have you seen this?

LikeLiked by 2 people

No, I haven’t seen the elephant documentary. I might avoid writing about the topic while living in the region. One really doesn’t want to piss off the government when one has to go to immigration often to renew ones visa. But I’d like to see the video.

Nolde is an amazing colorist. He’s got some wonderful landscapes as well. completely underrated.

I’ve never read Rand, I just mentioned her in connection, I think, with those documentaries by Adam Curtis. I remember now. Silicon valley was obsessed with Ayn Rand. She might be interesting. But, I think a lot of people find her politically objectionable from a political standpoint. I know Libertarians are particularly fond of her, for what that’s worth.

Lot’s of blues in one area sounds like a good thing. Those subtle permutations make all the difference, even if non-painters or non-aficionados might not realize why a certain shaded area is appealing.

LikeLike

Great post. It provoked me into a brief investigation. I notice in this …

http://quoteinvestigator.com/2013/03/06/artists-steal/

… that the conclusion is that there is scant evidence that Picasso ever quoted himself, something which occurs as a possibility as you read through the article. I also looked this up …

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/For_the_Love_of_God#Sale

… which suggests that Hirst never sold the skull at all. This is something I’ve come across before in a documentary somewhere. I like David Lee’s comment that:

“Everyone in the art world knows Hirst hasn’t sold the skull. It’s clearly just an elaborate ruse to drum up publicity and rewrite the book value of all his other work.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Jeff. I also checked the quote investigator, which is where I got the historical lineage of the quote, then cross-referenced it with Wikipedia. And, yeah, I’ve written about “For the Love of God” before (even did a parody video), so, know he may have bought it himself with some others… My main interest is, of course, how this quote is being used to justify plagiarism and the further disemboweling of artists in favor of opportunistic businessmen and oligarchs, who, via Warhol, now can declare themselves the true artists. [Note: thought I typed in “dis-empowering” but it ended up “disemboweling”, which, maybe I like better.]

LikeLike

Roy Lichtenstein copied hundreds of images from numerous artists without giving them credit or compensation.

http://davidbarsalou.homestead.com/LICHTENSTEINPROJECT.html

LikeLiked by 1 person

That, of course, is true. He made overblown comics his signature style as well. In his case, I think people knew he was borrowing from comics because it was impossible to hide. He was kind of a one-act show. I’ll have to look into him some more in the future. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I suspect that plagiarists will find anything to hand to justify their actions – doing so would be just another theft. Don’t you think that it’s on the web that the greatest amount of copying goes on? There have always been so-called justifications for copy and paste, but it’s always seemed to me that the fact that it’s possible and that it’s hard to prevent that seduces people into doing it. And now it’s less about rich pop stars being copied onto cassettes than it is you and I getting stalled before we can even start.

But it depends on what you mean by:

>how this quote is being used to justify plagiarism

Used by whom? Do Jeff Koons or Damien Hirst use the quote? Or is it that they just go ahead and ‘appropriate’ – I think that’s the favoured word in artspeak – and you’re connecting the acceptability of this with a more general social drift towards ascribing value to their actions? That is to say, taking existing objects, adding to them in the most minimal way, and then presenting the results as your own because of that minimal addition (and perhaps with more minimal here meaning more)?

Like the donut by the way. A stuffed toy might work too – or maybe a stuffed toy version of a donut.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Used by whom? Do Jeff Koons or Damien Hirst use the quote? Or is it that they just go ahead and ‘appropriate’?

I was addressing a general concept of art in which that quote can be used to justify appropriation, and gave an example of a critic doing just that. Hirst, of course has his own famous quote about stealing.

I don’t think Hirst or Koons or Prince have been relying on that exact Picasso quote since before their careers began, of course, but rather that the quote is part of a “narrative” and assemblage of beliefs that prop up appropriation and related conceptual enterprises as the highest form of art.

There are similar attempts to justify hiring people to makes ones work because old masters had assistants or protégé to grind pigment and so on. It’s the same sort of misleading comparison that tries to make things which are the opposite have the same meaning. The assistants of the old masters workers in his style and couldn’t do work he was incapable of for him…

My goal was to get people to reevaluate what the quote really means, and stop using it to justify a stance which is actually antithetical to it.

LikeLike

I was planning to do a blog post on this same topic next week. Don’t worry, I am not going to steal your ideas, lost lest because you have virtually written the book on the topic via this post.

I’ve always found Picasso’s quote interesting because of the different interpretations people get out of it. Overall, I think it is a positive thing when artists borrow from each other as that is the basis of culture and culture produces superior outcomes that individualism but I am thinking of the greater good here.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Feel free to address the topic 🙂

Artists borrowing and learning from one another is a good thing, and has been going on forever. Artists stealing from other artists and not having their own original ideas, getting away with it, and taking it to the bank is more of a new thing which isn’t as appealing, I think. But, yeah, there’s a level where everyone is influenced by everyone else (think early to mid rock music) and it’s a great thing. That, however, is not appropriation.

Cheers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! I learned a lot from your blog, and will return to learn more! Thanks for extending my High School Art Class studies! lol..enjoyed it very much! Teresa 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank Terese. So glad you enjoyed it and learned something too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I did a rendition of Van Gogh years ago and also a Rockwell, If your interested in checking it out ?? ladybuggz.wordpress.com/2015/08/25/an-artist/

Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

They are nice enough, but not an original Ladybuggz. I was more engaged by your story overall, and read a couple of your other posts. All you have to do to make your art more YOU, and complement your writing, is draw the stuff around you. Just a thought. Just throwing that out there. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

True! I’m working on it!! Thanks! 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

A wonderful, well argued diatribe. Thoroughly enjoyable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, thank you so much. When someone enjoys it, then I feel good that it was worth writing and compiling.

LikeLike

So true! Great piece. Banksy is one of the most. current examples. His mice he stole form a French graffiti artist from 1974. That was this artist deal in the fucking 70s hes legendary forgot his name have a few of his pieces when I used to go bombing, never know who you will meet. Didn’t get who he was or the big deal he was just cool as fuck and talented & a great teacher. By your title is exactly one of the biggest pieces of advice my father who is a legendary architect, artist and sculpture taught me when I was young.Why he told me is that ppl became epic and wealthy over doing this, its the method in which it was done that was genius. He physically showed me how its done. My dads works is out of a fantasy, dream its hard to explain, everything based on sacred geometry and metaphysics to provide the appropriate energy for the space. He studied around the world practices that are dying, he apprentices. Used history and education dude I wish I could do what he could do but I got my own plethora of endless skills that I keep perfecting and discovering. I dare to suck tho. But on the side when his large projects were in the works he’d do his sculptors for what I called rich people, completely diff style then his other work, not my taste and he’d somehow get away with doing replicas my forgeries are good I dabble in many kinds more as mind exercise see what I can do. But he totally jacks these famous fucking statues & does them with his hands, then acts as if its all him his creation and baby and has an entire synopsis for the story. I didn’t know till my mom pointed it out. He used his “glamour” & his personality to overshadow all he did was jack someones old legendary shit. That takes balls bc I am not going to sit and name drop my fathers clients, east friends or his works. To reconnect I thought we could do a tongue and cheek replica extraordinaire collection with a twist. he was like replicas to rich white American etc clients me NOOOOOO!Never!!! – Most important advice he ever gave me regarding my design and various forms of art was this just fucking do it. This came after we were abroad at a museum where some coveted nouveaux “modern” art was on display. I’ve got a great imagination and usually see the beauty or reason in almost anything but this shit I was like really Son some bouncy balls cut in half and shitty wire hanger type wire is 80k? My dad said the difference between you and that artist is they took the risk they dared to do it, they did it and kept to it.It didn’t mean they. thought it was any good sometimes just to see how to sucker someone in the art world with their pompousness. Basically for shits giggles and a nice check. The ones who are serious kinda want to punch out. I learnt as a professional dancer and specialist in the music industry why Britney does so well. Mediocrity how it makes it and thrives and becomes legendary. Fuck Diddy who hasn’t he sampled???!!!???

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting story. Thanks for sharing. yeah, “Just fucking do it”. Stealing other people’s work and just copying it is a way to make money, but not a way to make art, at least not ones own art. Why say something that’s already been said? It’s like raising your hand in a college classroom to ask the same question or make the same point someone else did 5 minutes ago because the teacher was impressed. You have to have something of your own to throw in the mix. And as you point out, a lot of that has to do with imagination. In fact, imagination may be the #1 requirement for quality art, but, is generally completely sidelined and absent in the most heralded contemporary art works. Who can figure out the messy art world? But what we can be more sure of is which practices are bogus or bankrupt, and that artists themselves deserve more of a say in it.

LikeLike

Huh, so Picasso never actually uttered the words. I think this saying became popular after Kleon’s book “Steal Like an Artist” hit the bookshelves, although he must have used it in the same context like you said, stealing in order to incorporate into one’s work. Not necessarily to improve the artworks, but to shed a new light on them. How arrogant must one be to think they can be better than Da Vinci? Aaaahhh and those quotes by Koons and Hirst really got my heart pumping. I’ll go chill now and think about your upcoming doughnut series. It’s so much better than Koons.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, thank you for being the first to acknowledge my donut painting idea! Yes, Hirst and Koons were the worst, until, perhaps, Martin Creed showed up on the scene. He’s the new pinnacle of BS art.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really salient points made here, Eric! My favorite quote: “Picasso was a bit like a kid whose doting parents tape his most careless scribbles on the refrigerator with excessive praise. He seems to have believed anything he tossed off was priceless, unalloyed brilliance. Paintings executed in an afternoon were exchanged for homes the rest of us spend lifetimes saving for. I suppose a more direct way of saying it is that a lot of his work is half-assed, and he didn’t feel he really had to push himself to get recognition.”

LOL. Also, I despise Koons and his ilk. I wrote my hand off in a contemporary art history exam in grad school, stopping just short of calling him a [bad name here]. Thanks for educating all on this controversial topic!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yup, art and artists are particularly prone to subjective, exaggerated, and even delusions appraisals. In a climate where everything is relative — and the truth is the most repeated lie – any kind of objective or anchored take on art is nearly impossible. The end result is the art world’s cherished contemporary art is a catalog of the artifacts of society’s neurosis, cheap self-aggrandizement, and various unhinged obsessions. There’s a reason contemporary art plays almost no part whatsoever in the lives of the majority of working people. The last time we had a high quality popular art form was the rock music of the late 60-s to early 70’s.

Koons is an art director, though that is now generally accepted as superior to being an artist. People will try to say that the old masters had assistants, which is true, but irrelevant. Their assistants worked in their same style as underlings, and couldn’t do anything the masters themselves couldn’t. They ground pigment and stretched canvases. In the case of Koons he outsources work he is absolutely incapable of doing himself to world-class experts to execute in his name. There is no old master who is not as skilled as his assistants. The claim is totally bogus, and cuckoo. I sometimes wonder if Koons is a real artist at all. I’d think a real artist would have a very hard time not getting his hands dirty making the art. He couldn’t resist.

LikeLiked by 1 person

BTW: are you familiar with the work of William Powhida, Brooklyn artist?

LikeLike

Never heard of him. Just looked him up. His work looks interesting, though at present politics have become so utterly toxic that I have a tendency to shy away from art that addresses them at all explicitly, even if I agree with the artist’s stance. From a brief glimpse of his art in a Google image search, it was pretty political. Nice pencil work, though.

In a nutshell, on the topic, I say that good art succeeds despite its politics, and never because of them. I’m sure there’s a lot more to his work than the political angle.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Eric,

How have you been? It’s been a while. I saw this big eyes movie a long time ago. I do like her paintings a bit.

I’m not going to say your wrong on your opinion about plagiarism at all. Just had one thought. I saw a video a while back of an interview with Yuri Bezmenov talking about how the communists use modern art to destroy a country. They promote terrible art because it destroys culture. I have a feeling a lot of these famous modern artists making millions on shit don’t know they are useful idiots. Or maybe they do and are fine with it.

Matt

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Matt.

That’s the guy! I’ve seen an interview with him where he talked about how the KGB was trying to destabilize America via “ideological subversion” and to instill Marxist-Leninist beliefs in the population. A big part of the stages of destabilization was “demoralization”. And it was programming people to not be able to recognize reality even when the facts were incontestable and evidence was presented to them. I didn’t see anything about modern art trends. I probably just saw a clip of the interview and not the whole thing. I’d be interested in hearing out his argument about art, but I can’t find it.

LikeLike

Excellent essay!

I only now have chanced upon your page via a Google search for the “art is theft” quote.

I was only dimly aware of Hirst’s name and his work not at all until seeing the examples herein. Not surprised he’s been sued.

There’s influence and homage, even appropriation if done right, but then there’s outright plagiarism and theft. In Hirst’s case, I’d suggest a total lack of empathy for his victims – a sociopath’s trait glossed over with hyperbolic rationalisations, egged on by the Art Business.

I’ve pretty much given up on Art ever since the Nineties, but moreso as the new century has advanced. Like the music industry and Hollywood, the Art world has given up even the pretence of authenticity; why bother if the rubes are prepared to pay upfront for the show?

Warhol’s observations on the art business were cynical but spot on, particularly in today’s environment. He would be chuckling loudly now, watching everybody scrambling for their 15 minutes (and more) of fame via social media, and would likely applaud the arrival of AI unassisted art apps, created merely by typing in words, waiting not much more than 60 seconds then receiving dozens of variations on a theme. Who claims creator’s rights in that situation? The person typing in the suggestions or the person who created the software? I typed in the word “mushroom” alongside various famous artists and the results were astonishing. Who gets the credit? Could I enlarge and exhibit such works as my own? Or copy them onto canvas and sign them “after Grosz” or “after Dali”?

I don’t have a problem with artists coming up with a concept and handing it off to others to execute, but I do have a problem with the lack of appropriate credit given. This is akin to animators slaving for months for low pay on award-winning anime and never seeing even their names in the credits roll (although this may be changing).

If something is a group effort, acknowledgement should be given.

One other area aligned with theft is forgery. Pre-eminent among art forgers is Elmyr de Hory, who faked works by Matisse, Renoir, Modigliani and more throughout the Fifties. He famously once stated, “Who would prefer a bad original to a good fake?” which brings us back to the likes of Hirst, who perhaps could be likened to a forger as opposed to an original artist?

An excellent exploration of the subject, which includes de Hory, Picasso and others and which widens into a discussion on creativity and art itself, is the brilliant Orson Welles film “F for Fake” made in 1973.

LikeLike

Thanks, Rex. I’ve located “F For Fake” (and if anyone else wants to watch it, it’s here, free, in full, and JD). It will be this evening’s viewing.

I happen to agree with everything you said in your comment, and was especially pleased to read your views on AI. I’m rather ambivalent about it, though not the points you raised, which I also feel strongly about.

I wrote the article 5 years ago, and not surprisingly, the idea that “great artists steal” persists unabated, despite it not only being a horrible and transparent idea, but the opposite of the origins of the sentiment the quote encapsulates.

Hopefully I’ve managed to persuade a handful of people, or at least make them feel less alone in their own conviction that something smelled awfully fishy in the art gallery.

Thanks again for the film reference. Really looking forward to watching it.

LikeLike

Thanks Eric. I hope you enjoy the movie. It’s full of Welles’s sly wit and the “fake” aspect pertains as much to the way the film is assembled as it does to the broader subject. As Welles once stated, it’s more akin to an essay than a documentary.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was a very unusual film, with some great ideas in there. First off, there was some intriguing historical information, such as that Michelangelo started as a forger, though that may mean nothing other than that he copied works of prior masters in order to train himself.

The disdain for experts was amusing, and seems true to this day. When I see the forged works that have passed for real pieces, so far they have universally been bad. There was a Chinese guy about a decades ago that got caught making lots of An-Ex paintings that were fakes, and they were pretty obviously third rate. It’s not a surprise that the experts often lack a competent artist’s eye for what constitutes any kind of real skill with the medium.

I found myself rooting for the forger, except that his work wasn’t every good. I suppose that’s a good sign, that a real artist’s work is difficult to fake. And Elmyr de Hory chose some soft targets, like Matisse and Modigliani.

That said, if some of his paintings really were good, it would be interesting to see a collection of them. I have maintained for years that if a fake is great, then it is a work of art on its own. That wouldn’t apply to a copy, but an “original” piece in the target artist’s style.

With the advent of AI, getting better by the second, plagiarism has become magnitudes greater a threat than it was a year ago. I suddenly realize as an artist myself, my only chance is to build on the small following I already have. Social media and the art markets will be flooded with tens or hundreds of millions of AI artworks, drowning out that achievements of humans in very short order. This is already an enormous problem on Deviantart, and in NFT spaces.

Incidentally, I have done some digital “forgeries” myself, though it is a very slim portion of my output, and mostly for purposes of parody and art criticism. My 2nd most recent post about artists being confined to just one style includes several examples [Basquiat, Koons, Meese, XCOPY]: Insisting Artists Work In One Style Limits Their Creativity

I think it would be very instructional to show why the fakes are NOT as good as works by the original artists. Sadly, rather than doing this, the “experts” (who may have fallen for them) instead seem content to bury the fakes out of embarrassment, or the inability themselves to tell the difference.

Note that because so much of art discourse of the last 50 years of so positions “ideas” in linguistics as the real purpose of visual art, using visual language, art authorities are more trained in obscurantist art theory gobbledygook than they are at looking at pictures. It is to the point of the ridiculous, sometimes, with art critics being borderline visually illiterate. That might sound like an overstatement, but imagine music critics who listen to music little, but read about and debate the ideas associated with it instead, and that is the contemporary art world. At least the one I have been most exposed to through grad school.

Thanks for the movie reference. Orson really impressed me, and not for the first time. I’m working on a video version of the post about artist’s styles, which should be out in 2-3 days. You might enjoy it.

LikeLike

Really nice read. Thanks for putting it out there.

I came across this because I was seaching for how often this kind of thing happens. I hope one day to be able to earn a living with art (or in the beginning at least make some money to be able to buy materials to make more), but I’m afraid to put work up on sites to sell. As a nobody with little to no money, I expect it to be hard to sell anything, while a renowned artist could come across my work and take the idea and change it just enough it won’t go against any copyrights and get the credits and the … credits, and I’ll be even poorer because my investment is not returned. Or maybe a Chinese company just copies my work 1:1 and puts it on all kinds of merchandise and nothing can be done about it. You can find many examples of that on the internet too.

But what can you do? Just take the risk or try to make a name with ordinary stuff everybody else is already making and just hope that you’re a true artist that can set himself apart by moving people with his work where others can’t and release the more original stuff later when you have a name and the money for marketing?

Another problem is that the art world is dominated and influenced by rich people that see art as an investment. They and critics and renowned artists that push certain ‘upcoming talents’ onto the public. Or you need to study at an art school first, learn how to make art according to their rules and create a network to get an advantage. It’s all so demotivating.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And then there’s AI. There may be a market for physical paintings. I work digitally, but with AI that’s a really tough market. I think are new artist would want to have some sort of presence in social media to validate that their art is their own. It’s all very trick right now.

LikeLike