What is it?

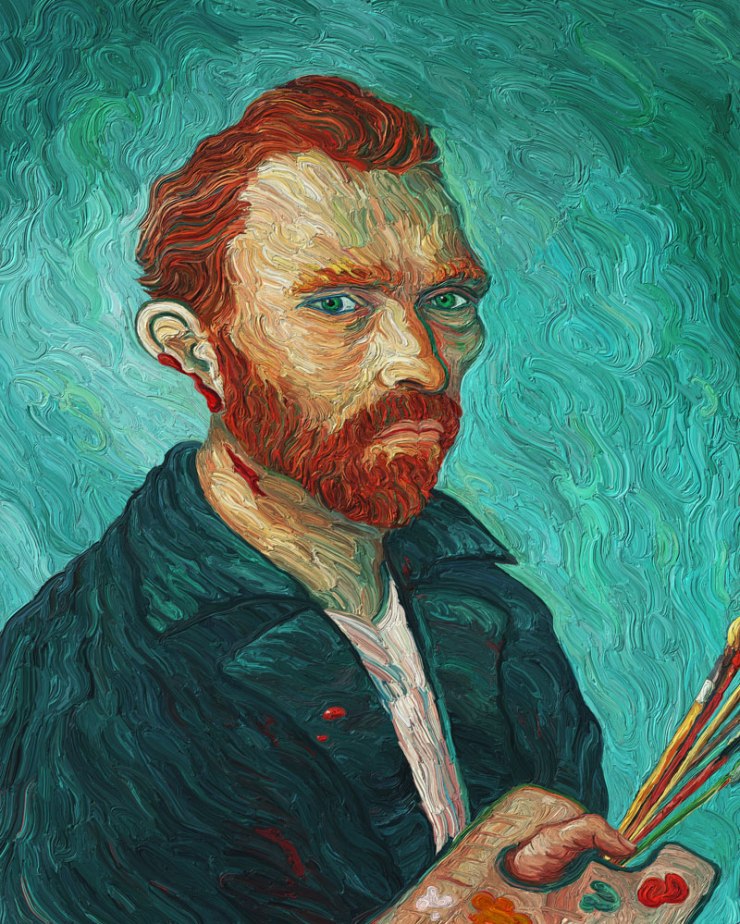

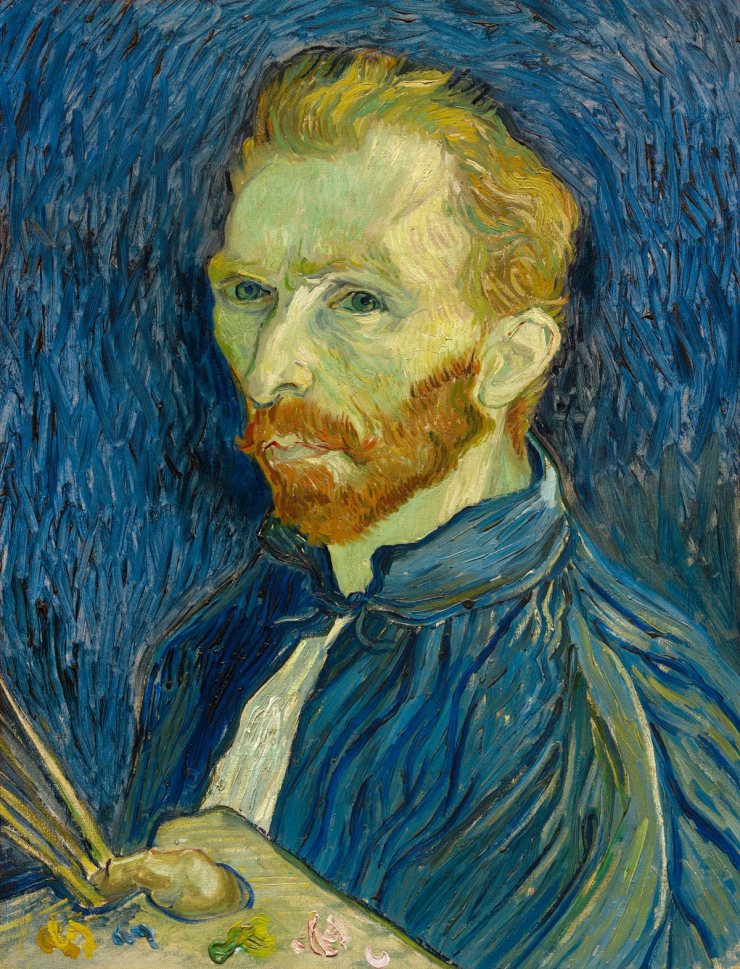

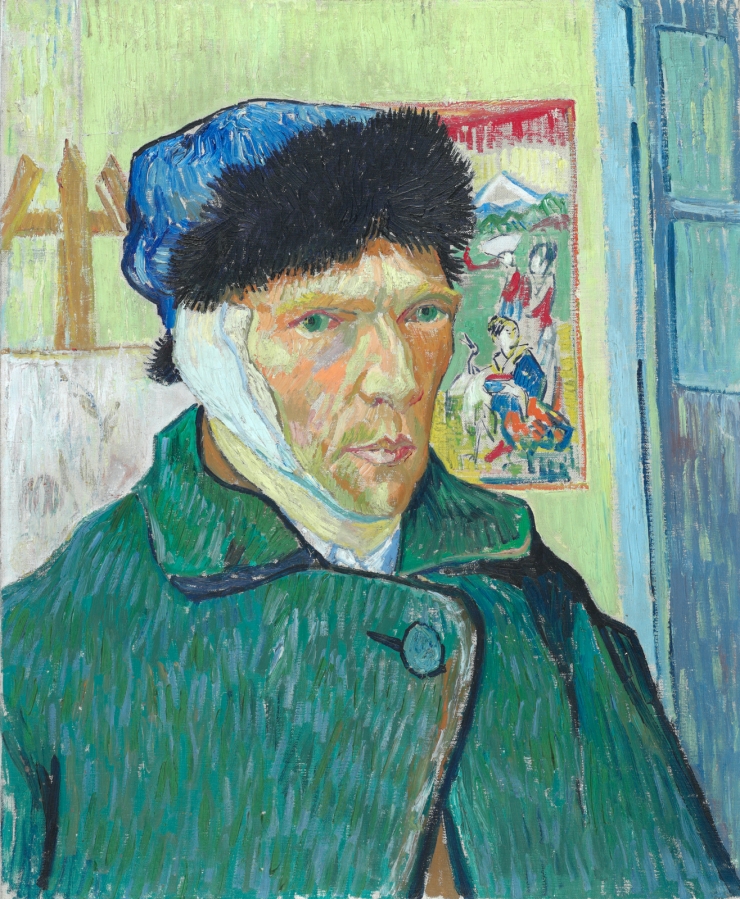

I hope it isn’t obvious what it is. After all, one of the challenges was to make it passably convincing, not only as a Van Gogh original, but as a physical painting. Several people assumed it was, though I don’t know if they appreciated how important and priceless an original, never seen before Van Gogh would be if it were suddenly discovered. It is, of course, neither a Van Gogh, nor a physical painting. It’s a digital painting of an imagined self-portrait by Vincent, with a freshly cut ear. I approximated his impasto brush work as best I could, and tried to capture a sense of his identity. It’s one thing to copy one of his portraits, and something else to try to create an original one in another medium. To the degree I pulled it off, it’s because I’m an ardent admirer of his paintings, and he’s tied for my favorite all-time artist. You can say that this is a tribute to Vincent, both his art and his person, and in his case his person is inseparable from his work. This does not mean it’s not an original work of my own. It’s also an attempt to build on the tradition of visual art he was a part of, and you can see his influence in quite a lot of my images. I hope this piece would appeal to fans of Van Gogh, and also that they might give some of my other work a chance.

the technique

People on occasion ask me how I achieve painterly impasto effects digitally, and my usual response is something to the effect that there’s no trick, and there are multiple ways of doing it, which is true. I’ve done it using Photoshop, Artrage, and Painter. The real problem is doing it well, which probably requires an analog drawing/painting background to begin with, and an appreciation of impasto painting. The computer doesn’t do the work for you. Each brush stroke is executed individually, and usually several times over. In some important ways it’s a lot harder than doing conventional painting.

People on occasion ask me how I achieve painterly impasto effects digitally, and my usual response is something to the effect that there’s no trick, and there are multiple ways of doing it, which is true. I’ve done it using Photoshop, Artrage, and Painter. The real problem is doing it well, which probably requires an analog drawing/painting background to begin with, and an appreciation of impasto painting. The computer doesn’t do the work for you. Each brush stroke is executed individually, and usually several times over. In some important ways it’s a lot harder than doing conventional painting.

I have a page of notes to keep track of my procedure for this work so that I don’t forget the order of doing things, which programs, which brushes, which settings, what to do with layers, and so on. Sometimes it works and sometimes it bombs. There’s quite a lot of trial and error involved, and the method that works for one image, or even one section of an image, may not with another.

I haven’t seen anyone else do digital impasto to the extent I have, and there’s even an article in a computer graphics magazine about my technique.

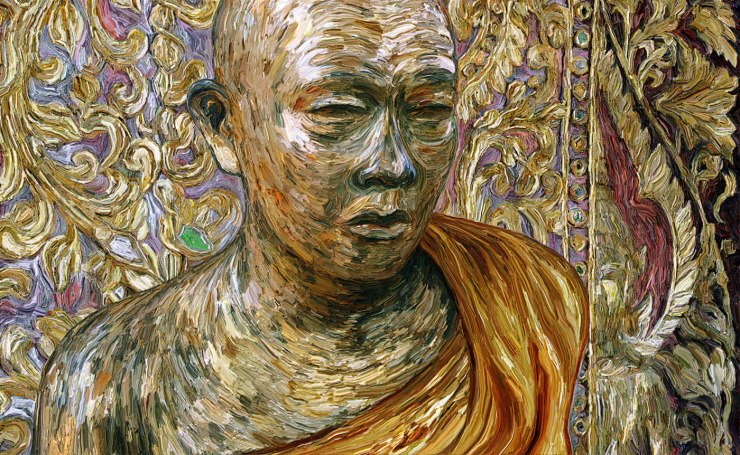

Here’s the first “impasto” digital painting I ever made, from 2004.

And here’s a click-through gallery with 27 digital impasto paintings I’ve made (newest first):

Incidentally, most of them are very large files and print big. My Van Gogh can print out at 4×5 feet (at 150 dpi).

Why Digital?

For those who are skilled with digital painting, or both analog and digital mediums, the more pertinent question might be, “why not digital?” It’s versatile, inexpensive, portable, environmentally friendly, tech savvy, futuristic, and looks great on the monitor. It doesn’t smell, doesn’t take time to dry, doesn’t have to be physically stored, doesn’t require a studio, and doesn’t ruin your clothes. More importantly for me, it allows exploring in uncharted territory, and combining traditional techniques such as collage, photography, and painting.

And perhaps one of the biggest criticisms of digital art is that you just can never do anything like Van Gogh.

I think a lot of people think of art or paintings as physical objects for sale. That’s a function of the end product, and of course you can sell high quality digital prints on archival paper in limited editions if scarcity is what people want. However, for me, the art is the image, and the canvas or print or monitor is just how my eyes access it. While I’ve been fortunate enough to eventually have seen lots of works in person, I learned to love almost all of them first as reproductions.

If the image rather than the artifact is paramount, I’m less concerned with how it was made, or what the medium is, than simply with what the resultant image is: what I see. I’m not concerned with image as object.

Objective

I’ve been making art since I was a kid drawing lizards, monsters, and spaceships. In art school I had a bunch of drawing and painting classes, learned photography, made sculptures, and in my final years focused on conceptual and performance art (because that was the era and climate of my art education, in other words, I didn’t have a choice.). Note that I only started to learn to use Photoshop AFTER I got my MFA, and it represented a departure, and perhaps rebellion, against the dominant paradigm that I’d been hammered over the head with for years.

Over time I’ve come to see my primary interest as visual art, and within that fine-art image-making. There’s a lot of confusion about the trajectory of art, with a prevalent general assumption that conceptual art rendered visual art obsolete (a mindset I dissect here). As someone who has made both traditional paintings and conceptual art, I see them as different approaches and different kinds of art, about as related as music and literature.

In this digital painting I’m trying to connect my practice with traditional fine-art painting, and as a continuation of it.

love of Van Gogh:

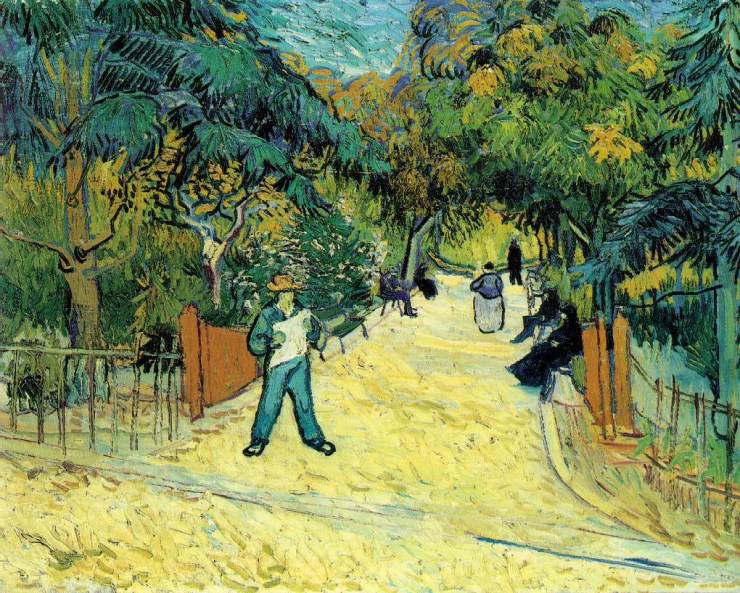

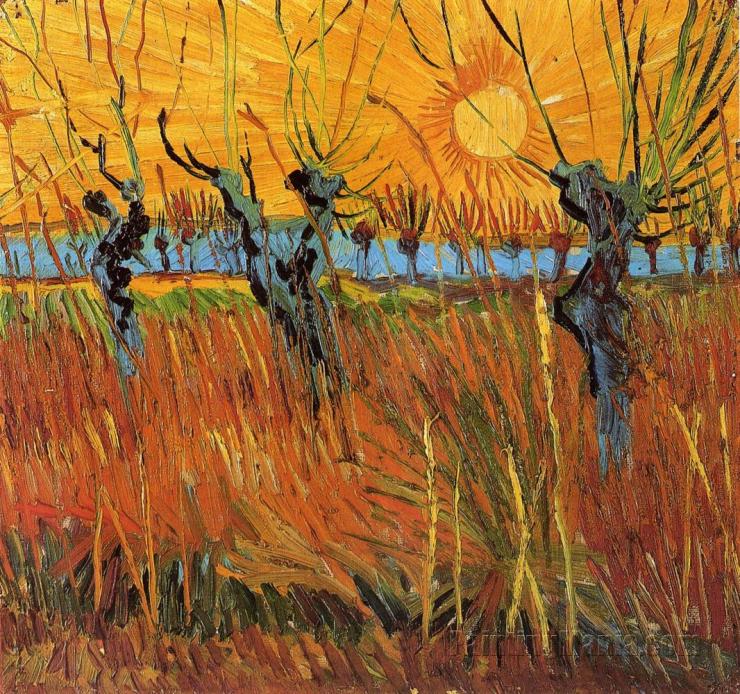

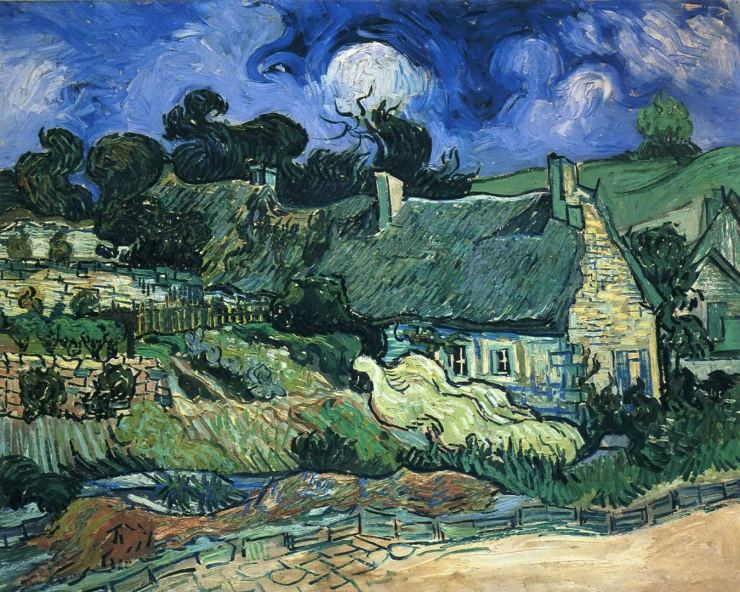

We all know Van Gogh is a whopping cliché these days. He’s been one since before I was born. The result is he is both over-valued and under-valued: over-valued for his celebrity status, and under-valued for his actual paintings. I think people admire his art, but I don’t think it’s all that easy. Art is a bit like math. The more complex it is, the less people understand it. Perhaps his paintings are readily accessible on one level, but on another are quite sophisticated. Everyone can appreciate the drama of the mad artist who passionately slashed at the canvas with loaded brush, painted at night with lit candles on his hat, had fits of insanity, cut off part of his own ear, and eventually shot himself in the wheat field. We can enjoy the vibrant colors, the broad brush strokes, and when he’s not too clumsy, some elaborately beautiful compositions. Feast your eyes on these:

On the other hand, his work is too deep to easily fathom. If you think he’s easy to understand, that could be a sign that you have only scratched the surface. Van Gogh is an artist I return to again and again and reevaluate as I myself grow and mature. I’m never disappointed. There’s a staggering humility to his vision, coupled with an equally astounding audacity. Both were apparent in his early works. He painted “The Potato Eaters” before he’d seen a single Impressionist painting, and if it were the only thing he painted, he’d still have made Art History in my book.

His own commentary best conveys his striving for humility in his work:

“You see, I really have wanted to make it so that people get the idea that these folk, who are eating their potatoes by the light of their little lamp, have tilled the earth themselves with these hands they are putting in the dish, and so it speaks of manual labor and — that they have thus honestly earned their food. I wanted it to give the idea of a wholly different way of life from ours — civilized people. So I certainly don’t want everyone just to admire it or approve of it without knowing why.”

He hadn’t learned to incorporate radiant color yet, but the draftsmanship of his mature style is already present, and the unprecedented thick paint strokes are beginning to appear.

We think of Vincent as a Post Impressionist, but really he’d already found his own vision completely independent of Impressionism, and he later merely integrated lessons learned from it into the thick groove of his own personal approach. He owes as much or more to his Dutch predecessors as to his French contemporaries.

Because he started painting late in life, his rendering of anatomy is sometimes so awkward it’s embarrassing. But Vincent, among all artists , is the one who most conspicuously turned his weaknesses into strengths, and in doing so moved visual art in new directions. Unlike so many artists whose ostensible revolutionizing of art issues from a deliberate, calculated, impersonal, and cerebral attempt to do just that, Van Gogh did it incidentally through his personal struggle to realize his own peculiar vision, manifest his ephemeral existence, and grapple with the human condition.

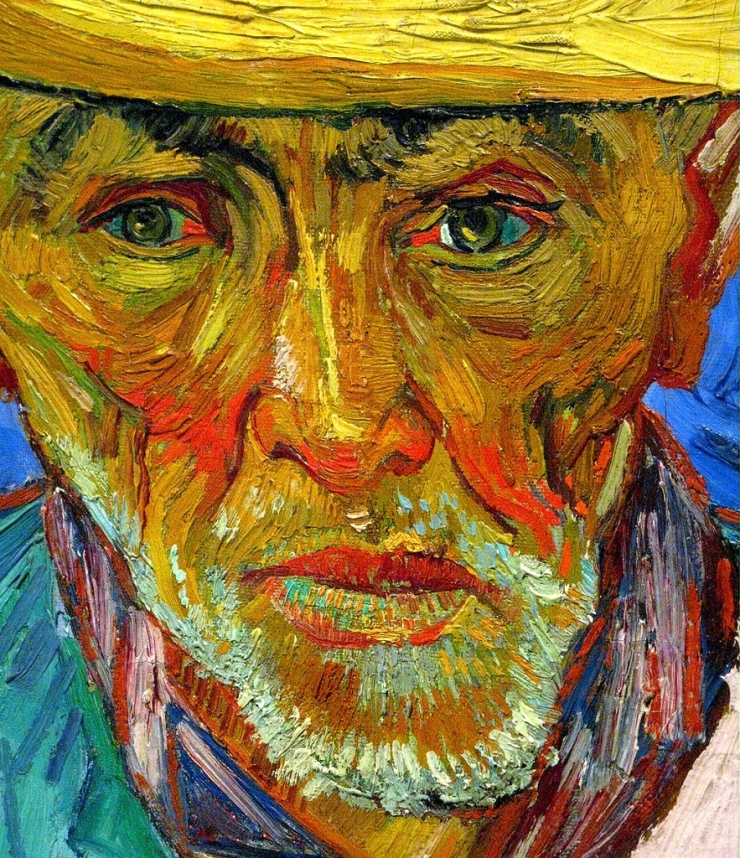

Doing this Van Gogh self-portrait makes me appreciate his work even more. After recreating something like his brushstrokes, I can delve into the face above and imagine painting parts myself. Vincent is a precursor to the Abstract Expressionists in that he, perhaps even more than they, made the process of painting visible and integral. Each brush stroke is directional, and we can recognize a methodology. Below you can see how I tried to create the directional brush strokes with all their painterly striations.

I used to have books of Van Gogh’s art, which I poured through, admiring individual brush strokes and juxtapositions of color. Always good to put some music on, pop open a thick Van Gogh book, and page through the familiar and not-so-familiar paintings.

I’m not trying to out-shine him. That’s impossible. You can’t actually make Van Gogh paintings without being Van Gogh, or at least trying to occupy his head (I guess there’s an element of character acting to it). I don’t have his temperament, and that’s probably a good thing. Well, who knows what his personality was really like. I’m just trying to learn from him, and, as I said before, carry on the tradition of what I call the evolution of visual art. Usually contemporary artists think in terms “revolution” and radically breaking from the past. That’s one approach. But I’m much more inclined to incorporate and integrate the past, while adding new subject matter, and techniques (such as working digitally). My last painting was of a robot attaining consciousness. Wonder what Van Gogh would think.

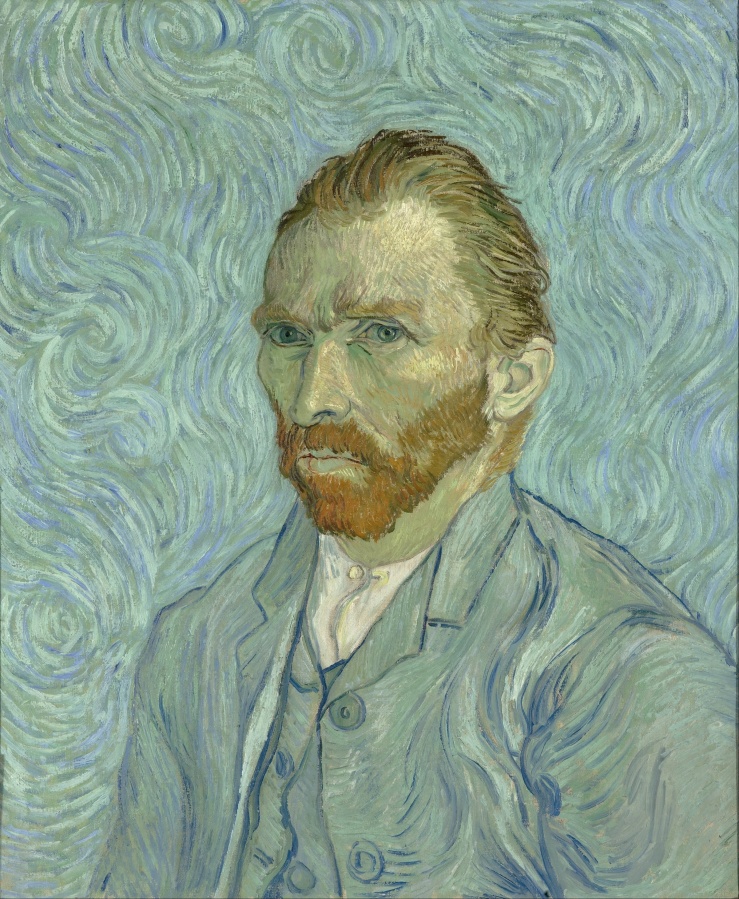

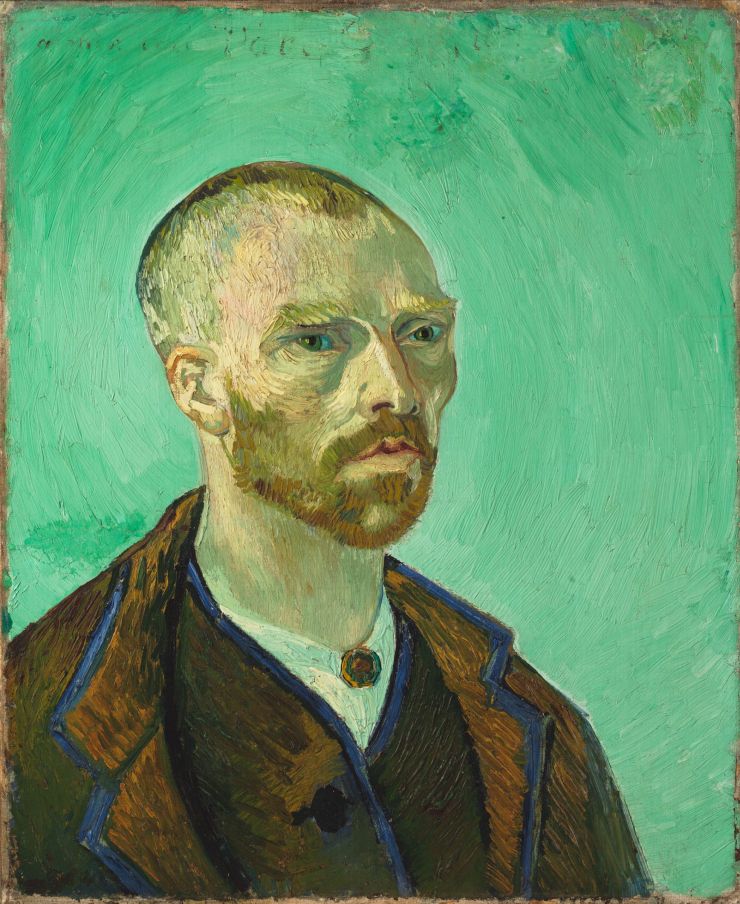

Van Gogh self-portraits i based my painting on:

To make my painting I studied a bunch of his self-portraits. These are my three favorites (and I’m sure these reproductions don’t do them justice because in the case of actual impasto paintings, they look very different depending on the lighting and shadows). I’ve seen a lot of his paintings in person, including at the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam:

And here are a couple closer details:

Dang. I forgot I’d found this ear detail, and didn’t use it as a reference. I just made the ear from my imagination.

Dang. I forgot I’d found this ear detail, and didn’t use it as a reference. I just made the ear from my imagination.

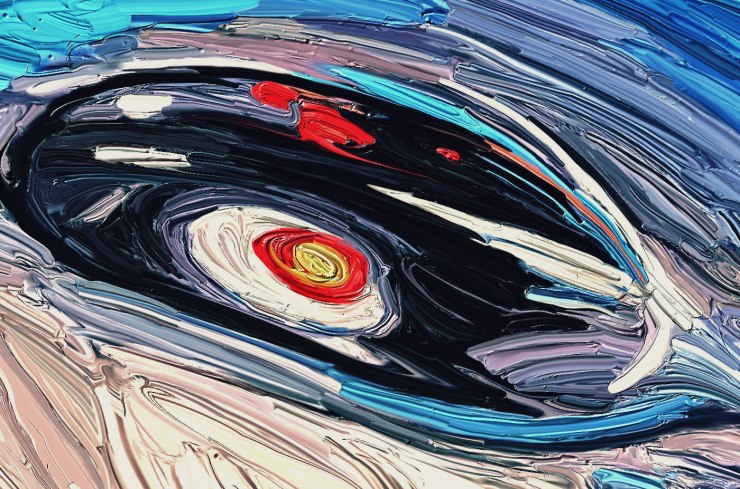

This eye, however, I returned to again and again.

I tried to get the quality of the eye without copying it too closely.

Initially, I decided to get off the ground by stacking a few of Vincent’s portraits in transparent layers in Photoshop, and then come up with an original based on them.

Initially, I decided to get off the ground by stacking a few of Vincent’s portraits in transparent layers in Photoshop, and then come up with an original based on them.

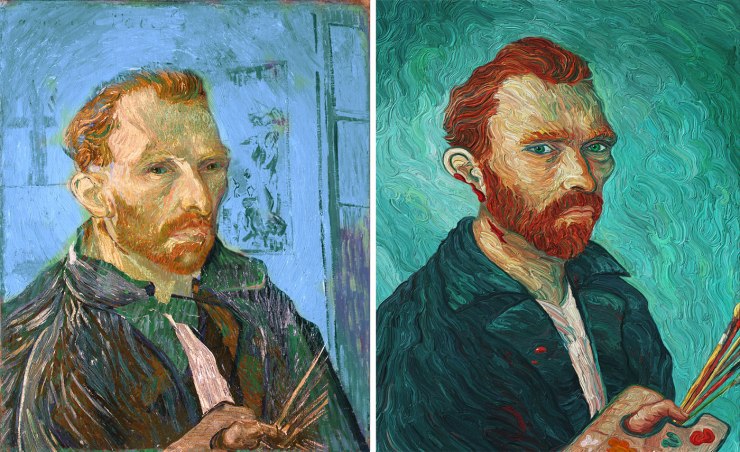

Below, on the left, you can see an early stage, and on the right the final image.

why the cut ear?

I had a strange idea the other day. It occurred to me that Vincent cutting his earlobe off might have been what secured his legacy, and not his actual paintings (though it should absolutely be the other way around). I guess that’s kind of obvious, but what is more intriguing is that he surely didn’t do it in order to be famous, but more likely in a climate of accepting that he was doomed to failure. He shot himself before ever getting any recognition, in which case I doubt he thought recognition was on the horizon, and certainly not fame and fortune. Tragicomic that acts born of desperation and hopelessness may have been what rescued his art from obscurity.

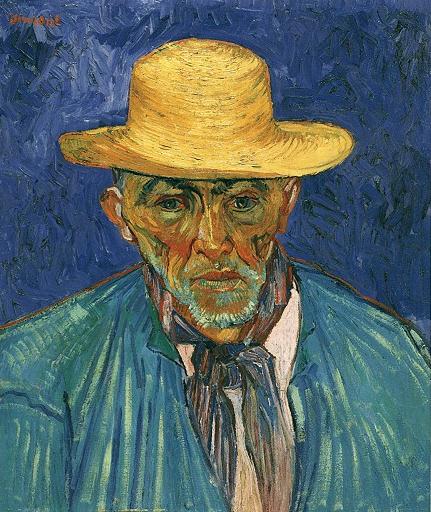

When we look at some of his more awkward pieces, of which there are many, and we shift our vantage to looking at them from the perspective of an audience that judges first based on fealty to reality, it’s easy to see how difficult it would be to accept Vincent as a great, or even competent artist. My first reaction whenever I come across the following self-portrait by Vincent is to cringe.

There are a lot of beginner type mistakes here, or at least what look like them. I even wonder if this one is a forgery. The ear is in side view, but the face in in three-quarter. The eyes are too close together. He has no chin, or cheekbones. The background strokes go from being entirely horizontal on top to a 45 degree angle below the brim of the hat. The hat itself is an abomination, and, the strokes along the front of the hat are completely horizontal rather than following the contour of the hat. If this is not a fake, it’s easy to see why a contemporary audience would reject this work as painfully clumsy. If this were the only surviving painting by him, I wouldn’t take him seriously. On the other hand, knowing the rest of his self-portraits, and seeing this in that light, I can appreciate this as a different angle in a stream of self-portraits, and imagine a glint in the eyes of a familiar self-appraisal.

Compare the portrait above to the much more realized and persuasive Portrait of Patience Escalier, below, with a much better hat.

It is easy to disavow much of Vincent’s work on technical grounds [while some, like his Irises, succeed on all grounds], in which case I really do wonder if it weren’t the sensationalism of his self-destructive actions that persuaded people to linger on his images long enough for the more subtle content to take root. Good art requires one spend some time with it to overcome the initial hurdle of incomprehension that one often experiences, as with a piece of music first heard, or the initial reading of a poem.

There are a couple other elements to Vincent’s short life that I find curious, and also make me ponder questions of time, and plausible greater contexts effecting events beyond our individual control or comprehension: one is that he must have appreciated his own work; the other is that he completed a complete body of work.

To think that a mature and advanced artist such as Van Gogh doesn’t appreciate his own work is as ludicrous as to claim Shakespeare had no idea how good his plays were, or Galileo couldn’t fathom his own equations. Thus, surely Vincent knew how great some of his paintings were, despite the seeming universal disavowal of them. How does one have confidence enough in ones own vision to persist without any support and in an environment of near complete disregard? I think for for Vincent this was a matter of seeing is believing. For the person who is visually intelligent and sophisticated, truth is most apparent in visual language. He must have had considerable cognitive dissonance in seeing for himself radiant canvases which appeared to others to be hopeless mush. When we tend to place faith in authority and numbers, how does an individual come to reject all of that in favor of his own unique angle of vision, and turn out to have been right?

When I think of Vincent’s untimely suicide, I tend to like to believe that if he’d just held out longer, even if he stopped painting and just worked some humble job to beguile the lazy hours, he’d have eventually been richly rewarded for his early struggle and enormous output. I might naively ask, “why did he give up so early?” But the much harder question, and the one that requires more empathy and deeper understanding of the human condition is, “how did he last so long?” I don’t know what his inner turmoil was like, and don’t think I’ve experienced anything like it (though perhaps I can imagine, as I’ve done in my tribute painting). What is curious, in relation to his conviction in his own art, is that he completed a comprehensive life’s work before dying. His final works are late works summing up his oeuvre, even if finished early.

In the final weeks of his life, and only then, Vincent painted on double-square canvases for a much more horizontal format. Many consider his Wheat field With Crows to be his last image, and though there’s some debate on that we’re sure it’s one of his last few. About these late landscapes Vincent wrote:

“They are vast stretches of wheat under troubled skies, and I did not have to go out of my way very much in order to try to express sadness and extreme loneliness…. I’m fairly sure that these canvases will tell you what I cannot say in words, that is, how healthy and invigorating I find the countryside.”

In the Wheat Field With Crows we see the visual equivalent of a literary denouement (unraveling of the knot). It has a finality about it that equals any other last paintings by any other artist.

Back to the ear. Vincent became more and more desperately unhappy before the fateful incident. As we know, he cut his ear after a fight with Paul Gauguin, after which Gauguin left Arles, where they had lived together for months in Vincent’s yellow house. Supposedly Vincent had a mental breakdown in the fever pitch of the drama, and had no memory of cutting his ear. He then packaged and delivered the severed lobe to a prostitute he was fond of, and was found unconscious by a policeman the following morning.

Later, Vincent wrote this about this period, “Sometimes moods of indescribable anguish, sometimes moments when the veil of time and fatality of circumstances seemed to be torn apart for an instant.” This appears to be two separate conditions, one of indescribable anguish within the fatality of circumstances (which would lead him to self-mutilation), and the other, moments when that curtain of doom was parted (his paintings). A painting with the cut ear is both at once, or rather the triumph of vision over circumstances.

That’s really something integral to appreciating Vincent’s art. There’s a quality of unreality to them, as in a transcendent, transportive landscape. He used painting to transcend reality, and to document the trip for us to see and share in.

Wherever the sowers in the following two paintings are toiling, it’s not Earth as we know it. The fields aren’t blue, and the sky (as in the bottom image) is not green.

Admittedly, I also chose a self-portrait with bleeding ear because of the drama and sensationalism. It’s almost impossible for me to reach a broad audience through just uploading my own art to my own blog, Instagram, and so on. Other people and other venues need to share it or within a few days it will quietly disappear from the radar. It helps to have something to grab the viewer’s attention.

~ Ends

You might also enjoy:

Vincent’s dead but he never gets old, and Jeff Koons is already a skeleton.

The Red Vineyard, and why Van Gogh only sold one painting in his lifetime.

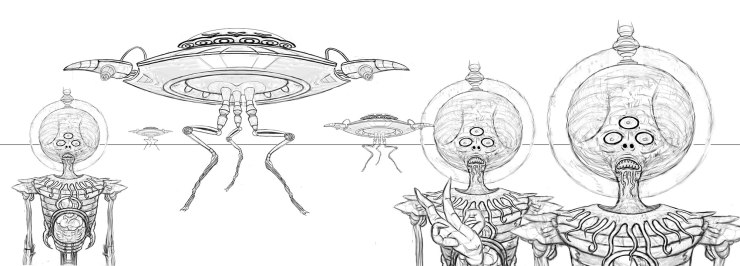

Now back to other and unrelated projects. Vincent is one of my very favorite artist, but only one of my influences. I’m currently working on my interpretation of War of the Worlds:

And if you like my art and art criticism, and would like to see me keep working, please consider making a very small donation. Through Patreon, you can give $1 (or more) per significant new work I produce, and cap it at a maximum of $1 a month. Ah, if only I could amass a few hundred dollars per month this way, I could focus entirely on my art. See how it works here.

Or go directly to my account.

Or you can make a small, one time donation to help me keep on making art and blogging (and restore my faith in humanity simultaneously).

Bravo. What a lovely tribute to Van Gogh and to digital art.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love Van Gogh! It is amazing what you can do with computers now, I would of never thought it wasn’t a real painting! Great Post! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Honestly, I think only I can do this with computers. The technique is my invetion, it’s my love of Van Gogh, and it’s skills and vision I’ve accumulated, including through my analogue paintings and drawings. I don’t think anyone else could do this. Thanks, though.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your tribute to Van Gogh looks remarkably like Eric.

LikeLike

Really? Well, of some semblance to me slipped in there somehow, that’s probably a good thing.

LikeLike

Vincent/Eric, two masters, birds of a feather. Compelling stuff.

I’ve always believed Vincent’s inspiration flowed from his superego, which was much more emancipated in him than most. His tenuous grasp of the traditional ego/self fostered a more phantasmal, perhaps universal, vision. Such is often the croce e delizia of introverts – some manage it well enough, others perish in the wake of its overwhelming “everythingness.”

Thanks for this vigorous piece !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Michael. I really appreciate your supportive comments. I think you are on to something concerning Vincent’s psychology, and a universal vision. There is definitely a transcendent quality to most of his work.

LikeLike

Amazing piece, caught my eye right away and even though I could tell it wasn’t Van Gogh, it was compelling. I had never given much thought to Van Gogh because of the commercialization of his work, until I visited the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam last year. It was then that I took a close look at his work and totally fell in love with his love and unfailing dedication to finding his own “truth” in his work, something he toiled to find. It’s utterly touching and fascinating.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In Arles he used reeds in his drawings. Did he experiment using reeds with the oil painting?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I never heard/read anything to suggest he used reeds in oil paintings. Something like that might be useful for sharp details. Perhaps in something like this: http://artsviewer.com/images/G/vangogh/1887-95.jpg

I never really paid attention to which brushes he used. In self portraits he can be seen with several. My guess is you can mix and match, and switch out some implements or others to get the desired effect. In the case of the read ink drawings/paintings the tool helped him get the desired look he envisioned.

Of course those things do matter, but I tend to consider them almost as little as I do whether a poem was written with a quill pen or in Microsoft Word. The outcome is what interests me. But, I’m grateful that there are people out there who are fascinated by what foes into pigments, how they are ground, what kind of canvas is used, front or back, and all those technical aspects of how to physically make art.

LikeLike

Thanks. He was an experimenter. hard to imagine after 100’s of reed drawings he would give up experimenting with reeds in oil. Reflex with reeds.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a question of whether it worked or not. Artists didn’t use quill pens in their oil paintings, so using an alternative for a quill pen for ink work doesn’t translate into using it for oil. It’s a bit like Michelangelo using a chisel for sculpting, and then wondering why he didn’t use it for painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

However, it’s possible Vincent would grab a reed and use it to scrape or apply a small amount of paint. Brushes allowed him to drag thick paint, and you can often see the width of the brush.

If he did use reeds for oil paintings, someone surely has observed this and addressed it in some detail. I may just be unfamiliar with the research, or forgot.

Thanks for reading and commenting.

LikeLike