[Why People Hate Conceptual Art: Part 3]

How the “radical” interpretation of Jackson Pollock privileges conceptual art over visual art, and his own.

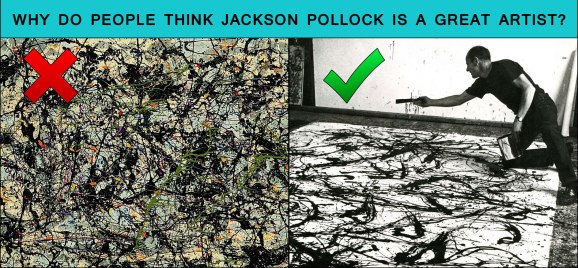

Attitudes towards Jackson Pollock epitomize the error of the perspective that conceptual art is a more advanced form of visual art. This viewpoint stems from thinking about art as a series of innovations that are important for changing the rules of the game rather than seeing artworks as inherently valuable pieces of communication.

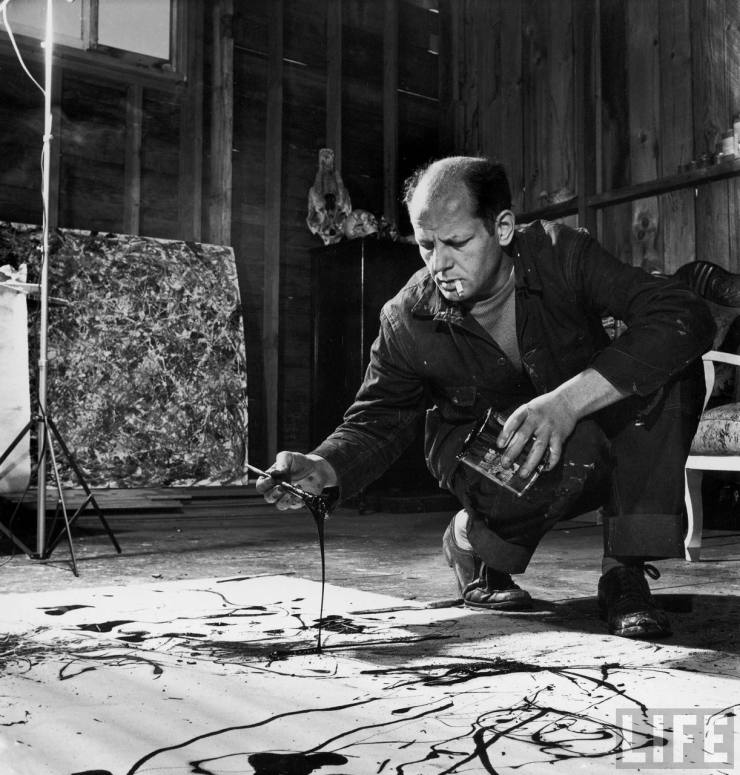

Many of us admire the paintings of Jackson Pollock for their richly complex, textured surfaces that emphasize movement and the painted surface of the canvas. Because there is no subject matter or composition, the paint itself and the application of the paint are forefronted as the subject, serving to make an existential statement that “this is what it is”: it is a painting of paint, and it is a painting of painting. There is no doubt that these paintings were intended to be looked at, and looked at some more.

For others, it’s not the inherent quality of his work that impresses, but rather the importance of his achievement. They will focus on the fact that he flung and dripped paint on the canvas rather than on the flung and dripped paint itself which makes up the final image. What they really cling to are the extraneous notions that – he was the first person to fling paint; he made a breakthrough; he is the father of action painting; and his work represents a radical departure with the past. This is a bit of a dramatization and oversimplification, or so I thought when I just wrote it. The section devoted to Pollock in Wikipedia’s entry on postmodern art, however, overflows with precisely this kind of rhetoric [underlines are mine].

“During the late 1940s and early 1950s Pollock’s radical approach to painting revolutionized the potential for all Contemporary art that followed him.”

and

“Pollock redefined the way art gets made at the mid-century point. Pollock’s move — away from easel painting and conventionality — was a liberating signal to his contemporaneous artists and to all that came after.”

and

“Artists realized that Jackson Pollock’s process — working on the floor, … essentially blasted artmaking beyond any prior boundary.”

None of this is about the intrinsic worth of his work or what his work hopes to convey. Instead, it’s all about how he allegedly changed the trajectory of art itself. This is not really what he was about, and it completely misses the point. So much attention is paid to Pollock painting on the floor, but it was largely a matter of convenience, which the artist himself didn’t think was anything special.

“I happen to find ways that are different from the usual techniques, which seems a little strange at the moment, but I don’t think there’s anything very different about it. I paint on the floor and this isn’t unusual – the Orientals did that.” ~ Jackson Pollock.

and

“It doesn’t make much difference how the paint is put on as long as something has been said. Technique is just a means of arriving at a statement.” ~ Jackson Pollock.

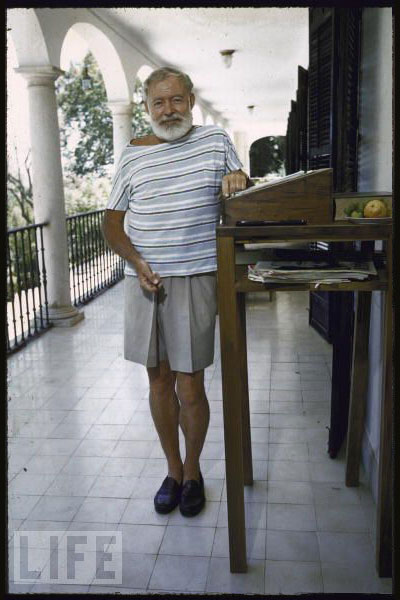

Technique, for Pollock, was a means to an end, and not in and of itself important. Valuing his work for the physical way he applied paint is akin to prizing the novels of Hemingway because he typed standing up.

Pollock’s art was not conceptual, and whether or not any of his methods or his vision represented a “breakthrough” was irrelevant to how you were supposed to access and assess his art, according to his own terms.

I think they (the public) should not look for, but look passively — and try to receive what the painting has to offer and not bring a subject matter or preconceived idea of what they are to be looking for.. .and I think the unconsciousness drives do mean a lot in looking at paintings… I think it should be enjoyed just as music is enjoyed — after a while you may like it or you may not. But it doesn’t seem to be too serious.

He didn’t want his art to be an illustration of a “preconceived idea” of action painting, and he wanted us to savor it like music, which means slowly and intuitively using the unconscious. All the hullabaloo about radical revolutions liberating art by blasting out all the boundaries of conventional art is extraneous bullshit for people who don’t or can’t understand Pollock’s actual work on its own terms, kinda’ like the people who love the idea of jazz but can’t stand to listen to it.

Here, I’d like to digress and share an anecdote from my childhood. When I was in high school, I used to go to a very dusty used record store and pick out albums to take home and listen to, mostly based on their covers. To this day, I see this as really getting to the core of art connoisseurship: acquiring mysterious envelopes that contain possible gems of transportive art, testing them out, and, if they are good, relishing them to the max (in this case, listening in the dark with headphones on).

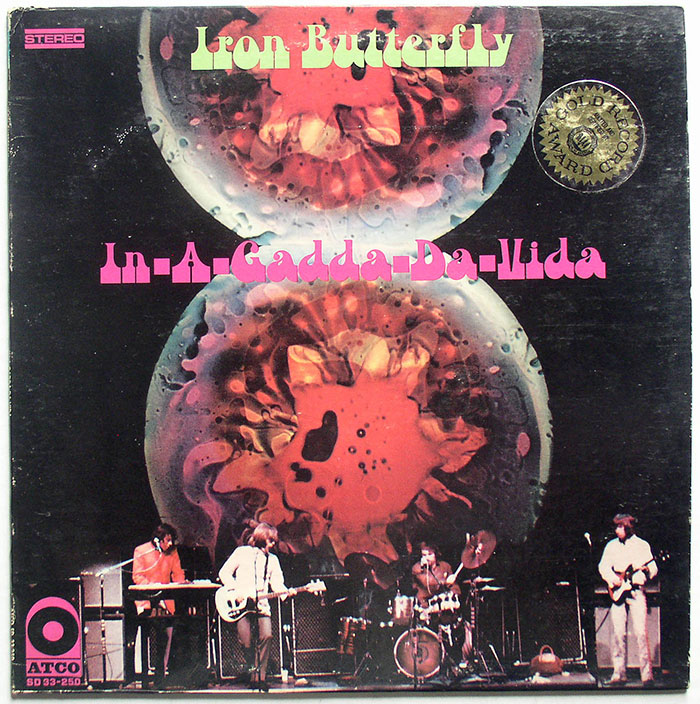

One day I brought home Iron Butterfly’s “In a Gadda da Vida’. I was drawn to the album because of the psychedelic cover. Even though they were a well-known band among rock aficionados, I’d never heard anything by them on FM radio in years of religious listening.

I put the needle on the record, and out of the crackling and hissing emerged a rising organ riff, and then some bass, and then a raspy guitar that had a particular sound that really appealed to me. I thought the vocals, lyrics, and everything about the music was excellent. It just had a mood that I dug, even though, or especially because, it wasn’t the music of my generation.

It was only a couple decades later, while reading an article on rock music, that I learned it was credited by some as the first heavy metal song. Since I was such a big fan of the song, I thought that was cool, but that wasn’t why I liked it. It didn’t matter at all if it was the first use of a distorted heavy guitar, the twentieth, or the hundredth. That’s just something to put on the back of the reissue of the album on CD to capture people’s interest. The music itself is all that ever mattered.

And so it is with Jackson Pollock, Frida Kahlo, Francis Bacon, or Francis Bebey (an extraordinary Cameroonian musician you might never have heard of).

Who cares what some art’s alleged contribution is if the art itself isn’t fantastic? Besides which, artists, like scientists, stand on the shoulders of those who went before them, and any perceived “radical’ change is actually just a demarcated scenic spot in a long journey of single, small steps. Max Ernst had dripped paint from a can onto a canvas on the floor years before Pollock did his first drip paintings.

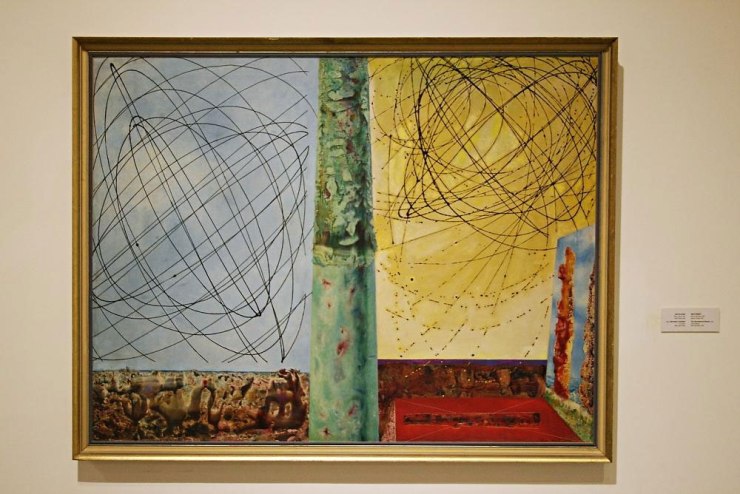

It is also now known that a Ukrainian artist, Janet Sobal, made drip paintings with “all-over” compositions a few years ahead of Pollock. We know that he saw them in Peggy Guggenheim’s The Art of This Century Gallery exhibit in 1945 and remarked to critic Clement Greenberg that they had made an impression on him.

Let’s look into this a bit further, with images. According to The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History “Pollock had created his first ‘drip’ painting in 1947, the product of a radical new approach to paint handling.” The painting that comes up in most searches as representative of his initial work with this technique is “Full Fathom Five” from 1947, which is roughly two years after Jane Sobal’s drip paintings were shown.

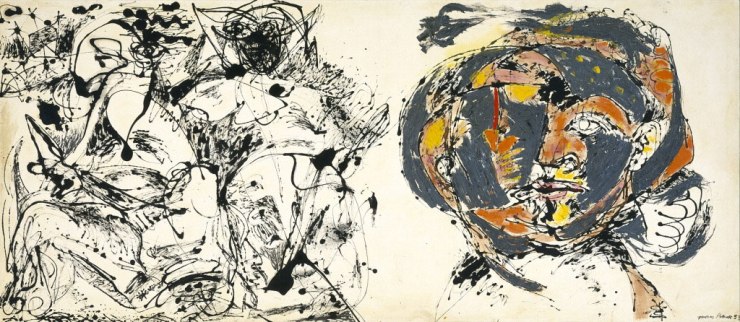

And here is Janet Sobal with a couple of her paintings that have an “all-over” composition and use dripping techniques, exhibited a couple years before Pollock’s radical discovery.

The untitled work of 1946 by Sobal plainly shows the same methods that Pollock is credited with inventing. If we entertain the notion that she really did prefigure his work, then the whole legacy of his importance as the father of action painting comes crashing down. We now have the Ukrainian grandmother of action painting!

Fortunately for Pollock, some of us like his work for what it is, and not for its pivotal role in a master narrative of modern art. I dig “Full Fathom Five, 1947” like I dig “In a Gadda da Vida”. I like it a lot better than Janet Sobal’s abstract paintings, but none of that matters if we are only interested in who supposedly did what first. There’s also an opposite art-historical model, in which Pollock is valued for continuing established traditions, rather than splitting from them.

Another way to look at it is that he isolated and emphasized certain aspects of painting that preexisted. A close examination of a Monet reveals that his painting also insists on its own physicality and makes the application of paint readily apparent, among other things, such as a deliberate abstracting of imagery in deference to the inherent logical demands of the painted impasto surface. One could make as solid a case that Pollock carried on aspects of the tradition of painting practiced by Monet as that he made a radical departure from painting of the past.

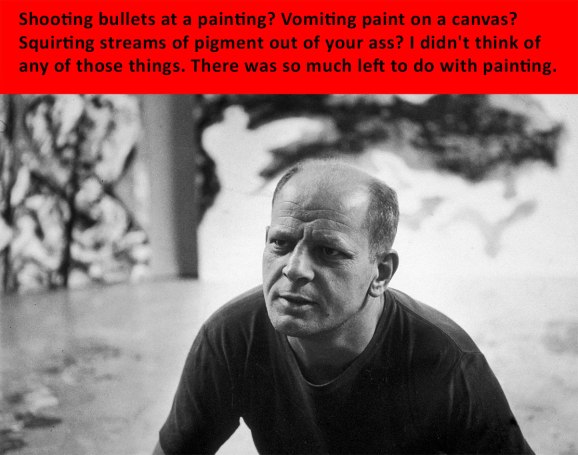

Heroizing Pollock for a perceived radical breakthrough misses the point entirely. It places value in an idea about what his art is rather than in the ideas his art is about. You wouldn’t even need to look at more than one or two of his paintings perfunctorily, and he wouldn’t have needed to have produced any more if what made Pollock a great artist was his invention of action painting rather than the quality of his artwork.

The picture above is what many people really value, rather than Pollock’s actual art. Yes, this Life Magazine photo has drama, and this kind of image helped popularize Pollock’s work and make it accessible to an otherwise initially uncomprehending general public. But it’s a picture of the artist, not a picture by the artist. Instead of looking at the artist’s painting, we are looking at the artist while he’s painting.

Conceptual/performance artists following Pollock – such as Yves Klein, Paul McCarthy, Carolee Schneemann, Chris Burden, Günter Brus, Niki de Saint Phalle, and Hermann Nitsch – took off from the “action” component of the work rather than the painting. They sought to propel visual art further forward, not by making a more evolved, complex, or integrated painting, but by doing more outlandish actions and forgetting about the canvas altogether. This did not build on Pollock’s art but departed from it, and was less an attempt to make art than just a shortcut to making art history. Instead of making art that was about the self, the self became the art. Aritsts started proclaiming themselves to be art, and perceived their role as taking the baton of art history and running forward with it. It didn’t seem to matter that they weren’t even using visual language, and had just adopted the conventions of acting and theater, including props, costumes, and set design.

This is not to denigrate the work of performance artists (I am a fan of Chris Burden), but just to not fall for the story that heralds their art as the next wave of radical breakthroughs in the history of visual art. Rather, they are attempts at a new kind of hybrid art that has about as much to do with visual language art as does cooking. A lot of their work was good for what it was (a quirky acting out of ideas), but it was not astounding for what it was not (visual art).

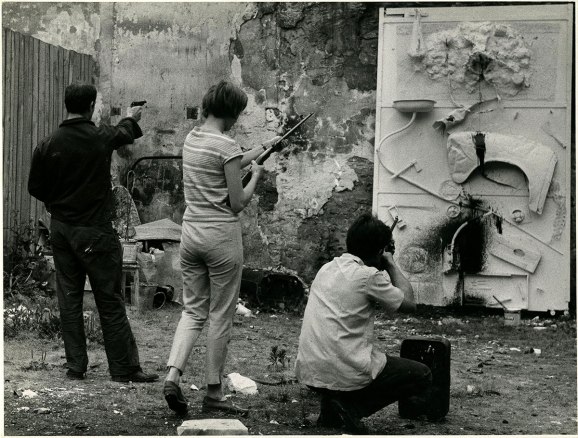

In the early 60’s, for example, Niki de Saint Phalle took Pollock a step further by shooting at canvases with guns. She didn’t shoot paint, but rather filled bags with paint, covered them in plaster, and then shot bullets at them. This is clever, and I’d probably have wanted to watch one of these performances if I were around at the time, but they miss the point of Jackson Pollock’s work and take “action painting” all too literally.

Dozens of artists found new ways to apply paint to canvas, but the end result was never as good as a Pollock or de Kooning painting. Ironically, while they claim artistic lineage to Pollock in order to legitimize their art as being in a grandly evolving tradition, their practice presupposes that it renders his work passé, as having been eclipsed by a succession of improved developments. Ironically, Pollock’s work was not going in the direction they took, and in his last works, he’d gone back to incorporating figuration. He was about the image, and the fact that he flung paint was no more relevant to his art than it was to Van Gogh’s that he sometimes squeezed paint straight from the tube.

Nevertheless, the successive tides of action painters continue to pound the shore, even now, over 60 years later, and are still considered radical. In 2014, artist Milo Moiré made a splash in the art world by hatching paint-filled eggs out of her vagina onto a canvas laid out on the floor.

Artist Millie Brown has similarly done radical paintings by vomiting up color on canvas.

Artist Leandro Granato can snort paint and squirt it out of his eye like a horned lizard.

Artist Keith Boadwee pioneered a new and radical way of expelling his demons on canvas by squirting pigment out of his anus.

By now, you may be feeling a bit nauseated with all the radical new ways of applying paint to canvas, and with the idea of radicality in art itself, which is about as sensical and appealing in 2015 as radicality in porn (anything that can still shock is probably not such a good thing). None of these innovations have anything to do with Pollock’s painting, or painting in general, and could all easily qualify as satire or parody if the artists weren’t deadly serious about their own self-importance (if you can take yourself at all seriously about sharting out streams of paint, it’s too seriously). Had Pollock lived to see any of this art, I don’t think he would have seen it as a validation of his own work. Rather, it might have struck him as a grotesque mockery celebrating the presumed annihilation of what he was trying to achieve: his art was contained in the subtle content and beauty of his paintings, and not in the mere act of dripping paint.

Imagine some students of the culinary arts learn to appreciate a certain chef for the way he cuts vegetables, swirls sauces, and flips omelets. In order to take this one step further they don’t restrict themselves to cutting on the chopping block, but do it all over the kitchen counter and furniture in the vicinity. They don’t just swirl sauces anymore; they pour them over themselves and roll about in them. And they don’t merely flip omelets; they fling them at passersby. The food becomes irrelevant. They got the gesture but missed the substance. And you have the same thing in these performance paintings. The painting is not worth looking at but merely pays lip service to there being a painting at all, which it does for the ulterior purpose of having a “commodifiable” object to sell. I do realize there may be attempts at some other messages about eating disorders, gender identity, and whatnot in those “performance paintings”, but none of that has anything to do with Pollock’s art either, nor does it necessarily rise above backfiring on inception.

Contemporary art has been painfully obsessed with being “radical,” to the point that “radicalism” has become entirely predictable, institutionalized, and has been a standard issue in art schools for decades.

Contemporary art has been painfully obsessed with being “radical,” to the point that “radicalism” has become entirely predictable, institutionalized, and has been a standard issue in art schools for decades.

When I was in art school over twenty years ago, we students would just try to come up with some new style or method of art-making. That IS the underlying ethos of art-making in the last 50 or so years. Art is the art of coming up with something new. And the important thing to notice is that this newness isn’t a kind of evolution, and doesn’t occur because the old forms are not plastic enough to convey new meanings. It really is just newness for newness sake, and it is a wholly conventional and even stale paradigm.. “Radical” is really “business as usual” in art school.

Keith Boadwee is an art teacher in California. Paul McCarthy was my teacher. Wait a second. Let me look this up. Yes, my guess is correct. Paul McCarthy was also Keith Boadwee’s teacher. You learn this sh*t in school. I did performance art in my “New Genre” class as well. Once, I brought a 5 gallon bucket filled with pig blood into McCarthy’s class, and while nobody was paying attention, I submerged my head in it for as long as I could hold my breath, and then sat upright without ever saying a word. I never thought I was being radical when I did performance art. I knew it couldn’t really be that transgressive if doing it was going along with my teachers, fulfilling academic requirements, and if it was what I was supposed to be doing to be taken seriously and have any hope of a career in art. In other words, making radically transgressive art was the norm, and a standard to be conformed to … OR ELSE!

To further illustrate the conventional mindset that contemporary art is a series of radical developments, consider the following excerpts from the section on Postmodern art in Wikipedia:

- Hard-edge painting and Lyrical Abstraction[37] emerged as radical new directions.

- By the late 1960s however, Postminimalism, Process Art and Arte Povera also emerged as revolutionary concepts and movements that encompassed both painting and sculpture.

- Groups like The Living Theater with Julian Beck and Judith Malina collaborated with sculptors and painters creating environments; radically changing the relationship between audience and performer

- There is a clear connection between the radical works of Duchamp… and Pop Artists like Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and the others.

That’s just one article, even if it’s in an online encyclopedia. Let’s see how many different articles I can find about contemporary art that use the world “radical” in their titles. I’ll sample from Hyperallergic, which is a NY based online contemporary art magazine I follow.

- The Radical Brazilian Artist Who Abandoned Art

- “Against the Art World and the World in General”: Painting as Radical Critique

- The Radical and Contagious Ideas of Lebbeus Woods

- Radical Archive Fever

- The Radical Boundaries of African-American Performance

- Radically Rethinking the Architecture of Death

- Revisiting the Radical Energy of 1968

- More Radical in China

So there you have it. The official history of modern and contemporary art portrays it as a series of ground-breaking, RADICAL movements, even when they are in opposition to one another. Someone who isn’t a part of the contemporary art community might see these successive movements not as radical leaps forward for humanity, born out of necessity, but rather as deliberate and even gratuitous attempts to make something extreme or ridiculous for the sake of it, resulting in a hollow radicality that is merely a game of one-upmanship, or artistic masturbation (which it sometimes literally is).

There are no doubt legitimate and tedious articles arguing why Vito Acconci’s “Seedbed” of 1971, in which he masturbated under a false floor in a NY gallery for a two-week show, was radical, pioneering, groundbreaking, and otherwise ushered in a new dawn of perception for humanity, opening our sleepy eyes that had not already been pried open by successive waves of prior radical achievements.

Let me just back that claim:

“To me, Acconci is a hero, and not just for his ultra-radical work. He’s proof that an ‘unconventionally attractive’ man, as I prefer to call him, can be a sex symbol.” ~ Art critic, Jerry Saltz, for Artnet.

Much of contemporary and conceptual art is this kind of game of ostensibly changing the rules of visual art, upping the ante of “radicality”, and taking oneself very seriously for doing so without even making visual art. It’s a bit too much like “changing the rules of chess” by playing hopscotch instead. I wish that artists who consider themselves above and beyond traditional visual art would do a bit of it just so that those of us who love visual art could have the privilege of seeing how far they took it before it imploded on itself. This is kind of like saying, “Let’s see the Kung Fu you can do; that’s just this side of taking it to a whole other, amazing, and unrecognizable level”. Show us how it’s really done before declaring yourself beyond it. In a coming article I’ll explore some conceptual artist’s after-the-fact attempts at making painting, most of which are dismal, because, as it turns out, they don’t have the skills to do it. [The radical masturbating artist, however, has gone on to make architecture, and some of my favorite kind: bridge overpasses for walking! I don’t think it’s radical anymore, but it sure is cool!]

Conceptual art frequently isn’t art about concepts as much as it is concepts about art, and concepts about art can get dreary, especially when the art isn’t even considered as relevant as the concepts themselves. A prop asserting visual art is dead undercuts its own self-importance by presenting itself as a comment on something that is irrelevant to begin with. And this brings us back to the beginning of conceptual art. In “Why People Hate Conceptual Art: Part 4” I will trace conceptualism back to its roots, and take a fresh look at Duchamp’s “The Fountain”.

~ Ends

Why People Hate Conceptual Art: Part 1

Why People Hate Conceptual Art: Part 2

Why People Hate Conceptual Art: Part 3 (that’s this one)

Why People Hate Conceptual Art: Part 4

Great stuff – I thought Pollock was a joke until I found one in the Art Institute – The violence and beauty – I did not expect it- I was hypnotized—-I really could care less about the “nuts and bolts” at that point of contact.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Cool. I’ve been moved by them in person as well. I can even get well into them in jpegs on the monitor.

LikeLike

Great article…”They got the gesture, and missed the substance”. I have always been drawn to the paintings of Pollock, but it was never the idea that he was radical or original that interested me. I just responded to the energy and atmosphere of the works, in the same way that some music resonates in an indelible fashion.

LikeLiked by 2 people

And that’s exactly how he intended them to be appreciated! Glad you enjoyed the article.

LikeLike

Love this series! As an artist that has always questioned the sensational nature of radical artists, feeling like it’s more about ego than art, this has been a cool and insightful perspective.

LikeLike

Thanks! Glad you enjoyed it. I think the biggest problem is that visual art and conceptual art have been put in the same category, and visual art gets judged by the standards that apply to conceptual art, in which case all painters are almost automatically conservative and irrelevant. There are 3 more parts to this series coming.

P.S. Looked at your blog and you REALLY are a great painter of waves.

LikeLike

I think your examples are clear and easy to understand and I appreciate an intelligent and open argument re: conceptual art. Although, I have to admit, I’m even more turned off by it than I was before. I had no idea that it had been taken so far out into left field and that everyone takes these kinds of things seriously. I can’t tell if I should laugh or cry, but history will remember it as “The Darkest Ages in Art” because it’s a farce and nothing more that missing the point.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I gave examples of artists who took off on the “action painting” element of Pollock’s work, and took it to ridiculous extremes. That is only one kind of conceptual art. There are much better examples, and I’ll share some of those in the part about conceptual art I like.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I know, it will be good to see the other side because this side is frightening.

LikeLike

You nailed it Lani – More than a farce…. I believe it was a hoax. A swindle.

LikeLike

I’m sure Pollock was genuine. People genuinely believe in all sorts of things. I’m sure you can come up with examples. However, I do think Duchamp’s “The Fountain” was a prank.

LikeLike

Theyre shit. People are sheepish they only follow what other say is good. I either like something or dont and dont give a shit who agrees with me.

LikeLike

What’s shit? Jackson Pollock paintings, or the people who like them for the wrong reasons?

LikeLike

I agree with you. Pollock himself agreed. He wanted to paint like a regionalist, but he wasn’t talented enough. He himself said a painting is nothing if it isn’t narrative. Meanwhile – Clement Greenberg used Pollock to further the notion that conceptual art was the only true art… propaganda first promoted by our own government. Look it up.

LikeLike

And yet Abstract Expressionism isn’t commonly considered conceptual art. It’s considered painting.

LikeLike

Thanks for this post! I think this type of attitude towards art has become too pervasive- especially in high school and college. Most courses that I have taken about film or literature focus on the political/cultural significance of the art instead of the actual piece. Perhaps this is naive, but I think the aim of art/film/literature criticism should be to articulate the feeling of the piece in such a way that the reader gains a deeper appreciation of the film/painting/etc.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I agree with you that looking at art through the lens of politics misses the point of art. Of course it’s worthwhile to look at the socio-political implications of art, but it’s a secondary consideration. For example, most artists, at least in the past, did not become artists in order to address politics, and in some senses assessing art via political criteria is as logical as judging cuisine on the basis of politics, and not addressing flavor.

Feeling might be a bit subjective and hard to focus primarily on, but there are a lot of different angles on can use for discussing art. But I would agree that feeling is more important than politics when discussing art.

Imagine discussing music only though politics, largely reducing much of music to the lyrics only. All guitar solos would be dismissed as emblematic of the male orgasm. Zeppelin would no longer be listened to, remembered only as white musicians who stole from black musicians without acknowledging them.

Politics are, well, politics. And I wouldn’t be surprised if the people who primarily see art through the lens of politics love politics first, and art not so much at all really.

LikeLike

I am a fine arts (sculpture) student from India. Your thoughts here have been a serious revelation to me. It has already affected my work in profound ways and will genuinely help me better my work in future.

Thankyou so much and looking forward to your next post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent article. You could make the same argument about Basquiat. People reference the child-like execution of the imagery. They fail to see how rich his work is with social critiques and observations. When you really dive into his work, you are awe-struck at how deep it is.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Matt:

Glad you like the article. I don’t have a strong opinion on Basquiat. I’m generally favorable to him, but don’t know enough and haven’t seen enough of his work to really dig in. I thought the movie Julian Schnabel made a self-aggrandizing (for Schnabel), and condescending (towards Basquiat). I learned next to nothing from it, except that perhaps Schnabel’s ego is a big as his over-sized canvases, though I think I like some of his plate paintings a bit. Anyway, I’ll have to explore Basquiat more in the future. Thanks for reading and writing.

LikeLike

Your dead on. I would take Schnabel’s opinion with a grain of salt. They were rivals and I always thought it was ironic that he of all people would do a biopic on Basquiat. There is an excellent book, Basquiat: A Quick Killing in Art, that really gives a more accurate depiction of Basquiat and Schnabel. It’s accurate because they humanize Basquiat as opposed to lionizing him. He was equal parts victim and victimizer. He knew how to play the system, but he was also exploited by the same system. It really is also a great read just on the inter-workings of the 1980’s art scene in New York.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’ll have to check it out. Living in SE Asia (right now I’m in Cambodia) I don’t really have access to good art books, so have to content myself with whatever I can find online (and don’t have to pay for). Sounds good though and I’ll try to keep an open mind about Basquiat.

LikeLike

I understand. That’s good hear. It’s hard to find good art books in states at times.

LikeLike

Nice. I did not appreciate his work until seeing big show, then it was deepened by reading about him, and having kindergartners talk about his work. Kindergartners are not intimidated by what they are supposed to think, and got right to the heart of his pictures – mythic war, nature, shallow visual depth. All his concerns.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading and commenting. I definitely enjoy Pollock, but, I do wonder if the drip style was a bit restrictive on his creativity after a while.

LikeLike

Always loved Pollock…Yet, have always believed that his very first drip paintings were done while seriously drunk…

Accidental – Not intentional.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s possible. He did get wildly drunk. However, he had seen a shows of drip paintings by Jan Sobel before he even started doing them. So, it could even have been a combo of things. Who really knows?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reminds me of Roy Lichtenstein seeing Andy Warhol’s Comic Book and Advertising paintings at Bonwit Teller in

New York City April, 1961 – This was months before Lichtenstein began using similar imagery in his work.

~ All the specific details are included on my Deconstructing Roy Lichtenstein website.

ANDY WARHOL AT BONWIT TELLER NEW YORK CITY APRIL 1961

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, I know about LIchetenstein. Not sure where I come down on his use of appropriation. He gets a few points for at least painting them himself and tweaking them out somewhat. I think everyone knows he’s copying comic books. That’s so obvious it doesn’t need to be said. So, part of it is blowing up little print dots to plate size. This is very similar to what Koons and Hirst and Prince and Glenn Brown are known for, though closest to Warhol, as they were both Pop artists.

It’s a rather complicated discussion of appropriation versus plagiarism, when it’s changing the original in a significant way, and when it’s just stealing outright.

I haven’t come to a conclusion on Lichtenstein. I’m fairly anti-appropriation, but I do believe in including contemporary subjects and techniques in ones art (as part of reflecting the world one actually lives in), it’s just a question of how that is done, and how it is integrated into an overall vision.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Enjoyed your point of view mostly I concur. Have a good day.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading and commenting. Glad to know you mostly see the matter the same. You might have some insight or angle that allows you to see some things that I don’t. I wouldn’t be at all surprised. Cheers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

umm actually i think you miss the point…..it seems because pollock wasn’t the first….blah blah blah….its irrelevant..his compositions are so ‘incredible’ as pieces of engineered colour….try to do a pollock?…try to mimic his work (if its so easy or common)?…see what your result looks like…no, pollock’s work is mesmerizing..but only for those that stare and look at them for long enough..most don’t then tangentially ramble off on some ‘mundanity’.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I made THAT point in my article. Not sure what I missed. The point is that his work stands on quality, not on being the first to do something. However, I disagree with you about his use of color, which, as an artist, I don’t find particularly interesting. It’s the energy and quality of line that make the images, by me. Though I do think he fell into a gimmick, and it’s a very limited, if potent style.

LikeLike

This was interesting, but for me you fail to distinguish between a ‘performance’ and an ‘action’. ‘Performances’ are transient things generally done in front of an audience or a camera that are contained within a time frame. Pollock was not a performer. An ‘Action’ is a decision of will, that has consequences beyond the gesture. This is where Pollock, uniquely, crystallised the moment of creative decision and, yes, it is absolutely to do with the way he approached his work, with his acceptance of his creative intuition and his explicit rejection of the derivative modes of painting that he had struggled with up to the point where he put the canvas on the floor. It doesn’t matter where he put it, no, but it matters that he took the mental step to put it there. The paintings for me hold the record of this fundamental artistic struggle of action over emptiness, and that is the foundation upon which all my subsequent formal enjoyment of his paintings rests.

LikeLike

Hi David: Thanks for reading and commenting. I’m not really clear what I am failing to see, or that I am indeed failing to see anything. Both “action” and “performance” (and we might as well through in “happening”) have more than one meaning as related to art. But, let’s go with your definition of “action”, and let’s see if I can gather what you are arguing.

You wrote, “An ‘Action’ is a decision of will, that has consequences beyond the gesture.” And this would NOT apply to performance or happenings, or Van Gogh or Monet painting? I’ve learned from comments on my blog that people express and understand different concepts differently. To me it sounds like you are stating that Pollock’s immediate aesthetic decisions were recorded as action (and inseparable perhaps from action) in the artifacts of his dripped paint. Thus, an elegant curved line of paint records trajectory, perhaps velocity, gravity, and an irreversible decision. This is the classic understanding of Pollock, that his painting is a record of a series of actions. If that is along the lines of what you were arguing, than I may not have failed as miserably as you thought. I may have thought everyone knew that as the most obvious reading.

In any case, that is tangential to my argument, if I am understanding you correctly. You need only look at the graphic at the head of the article to see precisely what I am addressing. Is Pollock appreciated for his paintings (you may define them as a record of his actions/decisions), or for the IDEA that he revolutionized painting, etc. This first option values his art for its intrinsic merits, while the second reduces them to props that signal his importance in a linear history of art.

I would also argue that Van Gogh, perhaps as much as Pollock, includes the action/decisions of his painting technique in the final image. Whether Pollock worked on the floor or a floating raft on the ocean, or the sail of a boat on the ocean in the wind while swinging from rope doesn’t really interest me if the resultant painting is not visually interesting. I am a fan of Pollock, but his technique is rather reductionist in the long run, and had he lived I imagine he might have moved on from his signature style.

Thanks again for commenting, and if I missed the point of what you were saying, feel free to elucidate.

LikeLike

Thank you for so clearly and precisely pointing out the failures of what is perceived to be ‘radical’ contemporary art, as well the intense and pointless narcissism of many on these so called artists.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes. I found myself today, while doing some complex tutorials on lighting and shading, marveling at how people can just presume to miraculously produce “radical” art that changes the course of art history, without having to really do any real work other than theorizing and networking and politicizing… You get a bright idea that vomiting paint on a canvas is important because it deals with, uh, people’s eating disorders and somehow Abstract Expressionism and everything that must be wrong with it, and you’re front page news.

Also, you might notice that today’s conceptual artists get themselves tons of coverage just by protesting paintings by old masters who weren’t exactly feminists.

And on top of it, it’s all so boring.

LikeLike