[Why People Hate Conceptual Art, Part 2]

Skill is generally a good word for visual art, and a bad word for conceptual art. For the conceptual artist, skill is largely irrelevant, or “busy work”, and would be dismissed as “unskilled labor” if that didn’t have the word “skill” tucked into it. Skill is seen as mere “craft”, and thus what an artist does with oil paint is really no different than what a cobbler does with shoes. For these reasons, conceptual artists are happy to hire highly skilled artisans to create their physical work for them, and don’t feel the need to give them credit.

Skill is generally a good word for visual art, and a bad word for conceptual art. For the conceptual artist, skill is largely irrelevant, or “busy work”, and would be dismissed as “unskilled labor” if that didn’t have the word “skill” tucked into it. Skill is seen as mere “craft”, and thus what an artist does with oil paint is really no different than what a cobbler does with shoes. For these reasons, conceptual artists are happy to hire highly skilled artisans to create their physical work for them, and don’t feel the need to give them credit.

The far conservative end of visual artists and their adherents, on the other hand, see skill as identical to art, and often determine skill based on the technical ability to draw hands, paint a horse, or otherwise replicate the physical appearance of things. They are the ones who accuse, “My 6 year old could have done that”, when they see a piece that doesn’t show those easily recognizable draughtsman’s skills. The famous painting of Ophelia, below, by John Everett Millais would probably satisfy all of them. This is the kind of art that art students tend to love in their art history classes, and the teachers tend to try and steer us away from.

Both the positions of the conceptualists and their opposites miss the point. The more conservative artists mistake facility at strict representation for the only or most relevant skill, and the conceptualists conveniently forget that visual art requires an underlying ability with visual language that must be cultivated.

Where the traditionalists can go too far

All great visual art requires skill, but not all skilled art is great. The internet is flooded with examples of people making painstaking pencil renditions after photographs, or of still lifes, and the results only show perseverance and practice at a largely mute art. The artists making them didn’t have to think about the subject matter, the composition, what to emphasize through distortion or abstraction, or even color: they just made elaborate copies that endeavored to look as close to a photo as possible. This rule also applies to contemporary artists doing the same thing, but instead of using pencils, they use painted toy soldiers, Lite-Brite pieces, push pins, coins, chewing gum, or whatever else they can think of. Those works are mostly about patience and mimicry, and all of them use a grid system, and/or a projector.

Anyone can appreciate the technical skill that goes into a realist image, and the odder the materials it’s made out of, the more we are impressed with the end results (at least until we see a half dozen different artists do variations on the same thing). Below, Joe Black is working on one of the pieces in his series of portraits of world leaders.

Pictures of his work at odd angles are more interesting than the whole images. Here’s his Obama being loaded onto a truck.

Seen head on, his portrait of Bowie ends up looking like a “fan art” tapestry.

This next image was done by another artist, Zac Freeman, only instead of painting small objects and putting them in a grid system, he used discarded everyday objects.

My guess is a lot of people are blown away by these, because this is the sort of art that’s always popping up in my Facebook feed. After a couple years of seeing similar work, I’ve lost interest, even if the results are spectacular on the surface. My point is that this is the sort of “skill” that everyone can appreciate when it comes to art = mimicry (and the obvious labor that produced it). But this fealty to the appearance of physical reality only goes so far.

I don’t recall Vincent Van Gogh ever fully mastering realism, and his early works were sometimes painfully clumsy. Look at the image of his “Potato Eaters” below, and notice how the woman on the right’s left arm is much longer than her right arm, particularly the span between the shoulder and elbow. All the steaming beverages she’s pouring are going to end up scorching the girl, because the table is tilting down in the front at a steep incline. Meanwhile the back of the man’s chair on the left is bolt upright at 90 degrees, parallel with the edge of the canvas, while the seat is at an exact right angle, even though the chair is turned away from us. We are looking down at the table, but up at the lamp. That (unintentional) optical illusion is worthy of M. C. Escher, or René Magritte!

This painting, which the great artist spent a couple weeks polishing, is a hopeless abomination from the perspective of a beginning drawing class. Nevertheless, it is an amazing achievement in painting, which despite being a compendium of technical errors, is coherent and succeeds by its own inner logic – it looks good. If you turn it upside down, so that you don’t worry about the whole family suffering from inherited birth defects, you can see that it has a structural integrity in terms of color, line, movement, composition, and especially lights and darks…

Sure, the girl in the foreground is smack in the middle of the image, and would have been better moved to either side, compositionally speaking, but when you consider his motives, and that seeing the potatoes and the drinks being poured were essential to him, it can be overlooked.

I know I’m going on a tangent, but I’m researching this as I’m writing it, so I can share accurate information, and I just happened upon a painting by one of Van Gogh’s two favorite artists at the time, and it’s very relevant to the argument I’m making.

Vincent had written to his brother about his admiration for Jozef Israëls, and disinterest in the Impressionists.

- When I hear you talk about a lot of new names, it’s not always possible for me to understand when I’ve seen absolutely nothing by them. And from what you said about ‘Impressionism’, I’ve grasped that it’s something different from what I thought it was, but it’s still not entirely clear to me what one should understand by it.

- But for my part, I find so tremendously much in Israëls, for instance, that I’m not particularly curious about or eager for something different or newer. ~ Vincent Van Gogh.

I think of Van Gogh as a “Post Impressionist”, and yet the Potato Eaters was completed before he’d even come to terms with Impressionism. Nevertheless, when you look at it, you can see many of the characteristics of his final works. Even if he’d never painted anything else, this canvas would still be a classic, partly because of its Earthy poignancy, but mostly for another reason. It looks like it was painted by a Potato Eater. He tried to paint with the same humility and roughness as his subjects, and the end result is that the style matches the content. We feel compassion for the family, and specifically because his rendition does not follow the laws of perspective or otherwise emulate physical reality as the eye sees it: a new, hybrid world is evoked, that is part consensual reality, and part Vincent’s own inner vision.

Israël’s “Peasant family at the table”, with it’s vastly superior and elaborate treatment of the chairs, and the cute little kitty-kitty, is sentimental in comparison, and the subjects a mere curiosity for the artist, who holds them at arm’s length. Vincent’s portrayal is intimate, earnest, humble, and his exaggerated use of line and form packs a punch.

While Israëls possessed superior formal skills, Van Gogh had greater artistic skill in terms of visual communication. When we think of someone proverbially making their weaknesses into strengths, Van Gogh is the artist who most comes to mind. His ability to actualize his own inner world is a kind of skill that is not mere craft, negligible, secondary to concepts, or can be assigned to assistants or hired artisans to execute in ones name. [For my argument against using artists assistants, go here.]

See my “Van Gogh Self-Portrait with Cut Ear” tribute painting here.

Where the conceptualists miss the point.

The conceptual artists appreciate that mere skill, no matter how highly accomplished, does not guarantee worthwhile art. It needs to convey something, be about something, and transmit ideas. But it’s as if they take this all too literally, disparage beauty in art as nothing more than decoration, and dismiss skill as a kind of belabored and ultimately futile fussiness. They miss that great art isn’t merely a display of virtuosity, or a tool to champion a particular idea or agenda, but is a subtle but powerful evocation of aspects of existence in visual form. It is a sort of alchemy in which, in the case of painting, inert pigment is infused with the quality of the living. Another way to put it is that great art isn’t the skill of craft, but the skill of transforming the inert into something like the transcendent or sublime [or possibly something humorous, ironic, thought provoking…]. Those words are so overused it might be better to say “something that is greater than the sum of its parts”, but that only works if you accept it as a way to tone down “sublime” or “transcendent”.

I’m sure a lot of people would scoff at that idea, because I was taught to ridicule it myself. I’m sure I would have smiled condescendingly if one of my peers at art school was dumb enough to claim to be chasing after the sublime. Come to think of it, I remember a fellow artist in my graduate program having the audacity to make abstract paintings in a climate where art was only considered significant if it was made in the service of a radical political agenda [Incidentally, as a straight white male, my only option was to “deconstruct my own white-male-privilege”]. The title of this guy’s show was “Exegesis”, which is a kind of not reading into a religious text, and I gather he was using the word as an analogy for not reading something into his painting other than what it was – a painted surface with its own existential qualities – while also insinuating it had a transcendent back door. When the professor asked him what “Exegesis” was, I chimed in, “It’s when Jesus leaves the room”. The instructor thought that was riotous. The artist didn’t. I mention all this for two reasons: one is to let you know that I know ideas of “the sublime” are anathema to the Postmodern paradigm of art; and the other is to emphasize that the conventional wisdom my generation of fine artists had ingrained into us was the conceptual framework (my graduate thesis show was an installation).

The more romantically inclined conceptual artists might say that their kind of work is a shortcut to the sublime, but doesn’t require all the tedious labor. Hypothetically that can be true, but if it isn’t done with visual language, it’s something else. As I outlined in part one, we can call this art, but not visual art. If you didn’t read it, this analogy sums it up. If you didn’t use musical instruments, or melody, or harmony, or rhythm, or even arrange sounds in a semi-coherent way, or even use sound at all…, you can call it art, but you can’t call it music. The point of this is NOT snobbery or preciousness about what is or isn’t visual art or music, but simply that visual art is the actualization of something meaningful through the means of visual language, and music through coherently organized sound…

Conceptual art undoubtedly requires some “skill”, though not likely the same skills as painting or other image making, or even anything roughly corollary. The expectation that art requires some sort of skill is aggravated when conceptual art is lumped in with visual art, or holds itself superior to more traditional work that requires obvious skill. A gun fighter has skills, and he can kill a Shaolin Monk, but he cannot say that his Kung Fu is better.

In 2012, performance artist mega-celebrity, Marina Abramović arranged a now infamous performance in which she sat in a chair in a museum for 7 hours a day, for three weeks, and anyone could sit opposite her and look into her eyes.

Generally people would get teary eyed looking into her eyes, as if they’d prostrated themselves before a celebrated guru. This performance required a lot of endurance, and a high tolerance for boredom, but none of the skills remotely associated with making visual art.

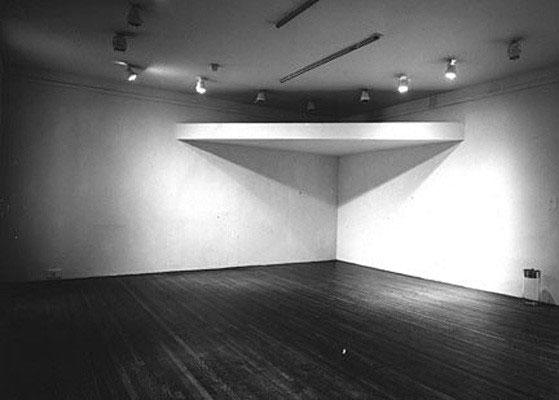

35 years earlier, Chris Burden had done a somewhat similar performance in which he remained in a gallery for 22 days (without leaving to go home like it was a regular daytime job), subsisting only on celery juice, and hidden from view lying in an elevated triangular platform in a corner of the building.

Another punishing endurance test, but, again, not a piece that required he’d ever picked up a brush, mixed a color, or even taken a photograph.

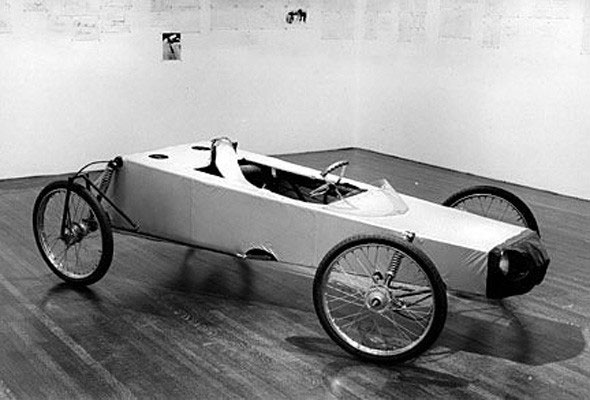

A perhaps more interesting conceptual work in terms of skill, also by Burden, is his B-Car, of 1977. Over a two month period he conceived, designed, and constructed a fully operational one-seater car.

Supposedly the vehicle you see above could go 100 miles per hour, and get 100 miles per gallon. Check him out behind the wheel, below.

Get your motor runnin’.

Head out on the highway.

Looking for adventure.

And whatever comes our way.

Engineering a car definitely requires a lot of skill, and I’m more impressed by the skills involved in that than I am by those employed in most paintings. Whether one calls it art or not, it’s still wicked cool, and I’m happy with calling it art; though it obviously isn’t music, literature, dance, or visual art, and there are similar creations that don’t call themselves art at all.

Just to really confuse things for a moment, and call all definitions into question, somebody is making a 70ft giant robot called, “The Bug Juggler” that will juggle Volkswagen Beetles. When completed, and with a few modifications to taste, this could be shown in front of a contemporary art museum as the crowning achievement of Burden’s career (or Hirst’s, Koons’s, or McCarthy’s), and museumgoers would be well impressed. The challenge that the robot poses to art goers, however, is that the mastermind behind it doesn’t have a degree in art – he’s a former NASA scientist named Dan Granett. He doesn’t even call it art, and the word “art” isn’t even used in articles about the piece.

Let’s say this thing actually gets made, and performs in some approximation as planned in the video below. I call it art, whether Dan Granett does or not, and kick-ass art at that. But it’s difficult to reconcile that someone could make a piece that trumps a great deal of contemporary art, and conceptual art in particular, without even thinking that he’s making art at all.

Somebody has got to have a good argument about why this robot isn’t art, and I’d enjoy sinking my teeth into the stances coming from either extreme. Could someone see Chris Burden’s B-Car as art, but not the Bug Juggler? Conservative, traditional artists couldn’t say it requires no skill, but rather just no painting skill. And what of the radical conceptual artists who the piece poses the biggest threat to? Will they argue that it has to say it’s art in order to be contextualized as art, in which case it miraculously becomes art if the creater asserts, “I forgot to mention I think of this as conceptual art”? Or will they just say the underlying idea isn’t artistic enough to qualify as contemporary art? Could Damien Hirst, with his solid repertoire of overgrown, teenaged-boy art reject this as not serious enough? From my standpoint, if The Bug Juggler isn’t art, neither is most conceptual art in the museums, art magazines, and on the internet. [See an article I wrote about the Bug Juggler here.]

How do we distinguish skills that belong to other disciplines, such as engineering, from art skills, when they are used in an art context? If Burden’s “B-car” is a work of art, how many other cars are as well? Why isn’t a drone or a bomb art? And if Abramovic’s “The Artist is Present” performance was art, why isn’t it art when the hugging guru Amma hugs her followers? She’s hugged over 30,000,000 people!

Weeks after 9/11 contemporary composer Karlheinz Stockhausen declared the destruction of the towers to be, “the greatest work of art imaginable for the whole cosmos”. He saw it as conceptual art. This is the logical extension of seeing any skill as artistic skill, and privileging anything that happens in the physical world over anything that happens in a mere image on canvas. By his same logic, Pearl Harbor, and dropping a nuclear bomb on Hiroshima were also great works of art.

When we dismantle Stockhausen’s argument, and reject the attack on 9/11 as conceptual art, do we also unravel the justification for other conceptual and performance works that have been widely accepted as art? That’s a meaty topic I’d like to return to another time. A possible angle with which to refute Stockhausen is that the 9/11 attack does not involve any deliberate aesthetics or beauty. For now, I’m going to accept for the sake of argument that conceptual art is art indeed (even if it might not stand up to the argument that proves 9/11 wasn’t a work of art), but I’m going to insist that it’s not visual art.

On both sides of the spectrum skill is confused with mere technical proficiency, where the real skill is the ability to make something substantive out of nothing, and in the case of visual art that means through using visual language. Conceptual art generally does not use this sort of skill, but can use other skills unrelated to traditional art-making in order to make a different kind of art and art experience.

I will leave you with two more art works to appraise for yourself. Both have appeared in my social media feeds lately. The first is visual language art by Peter Doig, who is one of the most popular living visual artists.

The image above is a very traditional piece which attempts to use the medium in a subtle and nuanced way. This is obviously the work of someone who’s studied fine art painting, but doesn’t accurately illustrate his subject matter. The painting has a dreamy atmosphere, and conjures a feeling of time spent alone, self-reflecting, in nature.

The next is a performance piece by Casey Jenkins which explores issues revolving around perception of women’s bodies; the womb and menstrual cycle in particular; and ideas of women’s work.

This is an endurance piece related to Abramovic’s “The Artist is Present”, or Burden’s “White Light/White Heat”, in that Jenkins spent 28 days in a gallery, sitting and sewing. Each day she inserted a ball of white wool into her vagina, and then continued to knit a long white ribbon with the thread as she pulled it out. The 28 days is intended to correspond with the length of the menstrual cycle, and during her cycle the white ribbon was stained with her blood. Her stated objective was to link the vulva with something that people find “warm and fuzzy, benign, and even boring” (wool and knitting), in order to “get people to question the fears and negative associations they have with the vulva”.

You can see a video about her performance below.

Both pieces are art, but they have nothing to do with each other and use none of the same skills, to the degree skill is relevant. Some would say the skill involved in the painting was dead on arrival, and others that the performance piece involves no skill whatsoever.

I think the performance has a lot in common with theater (it involves time, props, and a person doing something in front of a live audience), and little to do with visual art (unless staining cloth is thinly equated with painting canvas), in which case people are applying the wrong criteria. And unless there’s something wrong with theater that I don’t know about, I’ve never understood why “performance art” isn’t seen as contemporary, conceptual theater, instead of being lumped in with visual art.

In the end, visual art prizes skill because it is necessary for it to succeed, and conceptual art trivializes it because it doesn’t necessarily require it, and is even opposed to traditional visual language ability. This is like an owl and a snake getting into a battle, and the snake saying, “You can’t use your wings,” and the owl saying, “You can’t use your poison”. Conceptual art and visual art are apples and oranges, and can’t be judged by the standards of the other.

I believe most of the antipathy between the adherents of traditional visual art and conceptual art is due to the notion that conceptual art evolved out of painting, and then rendered it passé and irrelevant. Conceptualists consider criticism from painters a kind of pathetic, lashing out by conservative, craftsy “artists” who are hopelessly behind. However, the real aggression may belong to the conceptual artists who erroneously position their art as necessarily superior to painting, because it follows it in an art historical linear progression. Somehow it’s better than OK to pronounce painting dead, but if painters respond that conceptual art isn’t art, they are the bad guys. If the two approaches to two distinctly different kinds of art were seen as separate, I think most the antipathy would disappear. Figurative painters would enjoy creative performances and installations, but not feel threatened by them. Conceptual artists could appreciate paintings as the continuation of art in visual language, and understand that life without visual language art would be as undesirable as life without music.

Which you prefer, may just be a matter of taste.

~ Ends

Below are some of my favorite of my pieces.

And if you like my art and art criticism, and would like to see me keep working, please consider making a very small donation. Through Patreon, you can give $1 (or more) per significant new work I produce, and cap it at a maximum of $1 a month. Ah, if only I could amass a few hundred dollars per month this way, I could focus entirely on my art. See how it works here.

Or go directly to my account.

Or you can make a small, one time donation to help me keep on making art and blogging (and restore my faith in humanity simultaneously).

Great second installment of the series. I thought your examples were very good, as well. But since the last one is the one freshest in my mind, I’ll say, a lot of conceptual art seems like ideas that were made during “a night out drinking or smoking weed”. Yes, it’s sad that artists feel the need to do these kinds of things for attention, but even sadder is the warm reception they receive from the art world. Because the rest of us are thinking, “Vaginal knitting? Ewwwww.”

And so, I agree, let’s keep performance art with theatre….because they are obviously in the same family.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes. And I just saw yesterday that there’s a 21 or 22 year old artist who is doing an artwork where she will get a tattoo below the neck of anyone’s name who contributes a certain amount of money. The total she hopes to make is $10,000, so it’s not that much for each tattoo. She likes the idea of having stranger’s names on her skin. She’s getting a lot of attention for this, but it also seems a bit desperate and only marginally viable as art. It’s more like a publicity stunt, which, come to think of it, so is a lot of art.

LikeLike

Very good point. I think you nailed it. When did conceptual art become a publicity stunt?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can appreciate individual works from both schools, but I can’t generalize. It depends entire on the piece. The portraits above, done with toy soldiers and found items, are fascinating. The paintings don’t do anything for me. One conceptual project I abhor is Christo’s plan to drape 6 miles of Colorado’s Arkansas River with cloth — seemingly with little thought to the likely environmental impact.I think lawsuits stopped it, but I’m not sure.

LikeLike

Right, those paintings done with objects are very impressive. But, I’ve seen a lot of that over the last few years, because people figured out how to do it and jumped on the band wagon. The guys I shared do it extraordinarily well, however. Yeah, Christo’s plan doesn’t seem that necessary. We’ve seen things draped in cloth for decades.

LikeLike

For me, I love to see with my eyes. With skills or not, the eye has sensor like mouth, nose, ears and the rest of sensors. As long as you can see and the objective making your heart sing, what would really matter about how it is being done? With skills or not both could be visual from of art.

LikeLike

Yes, I think this is true. But, as with music, or even cooking, experience and skill are more likely to produce something shall we say “delicious”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article

LikeLiked by 1 person

Now where the author misses the point:

Conceptual art is not painting, not sculpture, not music, not theater. It is a category of art that is separate – and relates about as strongly to a painter’s skill as it does to a musician’s fluent reading of music notation.

The reason we cannot seem to find a good conclusion to this debate is because the debate’s various sides are arguing past each other. The sooner we are able to stop confusing conceptual art with other art forms, the sooner we are able to put this ridiculous disagreement to rest.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Misha:

Thanks for reading and commenting, but, it’s impossible for me to miss the point you provide, as it’s a point I’ve made many times myself, including in this article.

I quote my conclusion: “If the two approaches to two distinctly different kinds of art were seen as separate, I think most the antipathy would disappear. ”

This article is part 2 in a series. In part one I clearly stated, “It is a mistake to think conceptual art supersedes visual art, because the two approaches have different objectives and challenges, and are as dissimilar as music and literature. The conceptual approach is an alternative to art conceived in visual language, not a more advanced and encompassing development.”

You can’t use my own arguments against me to conclude I miss the point of my own arguments. It even sounds like you are quoting me when you say I miss the point.

You might as well argue that Christianity misses the point because it doesn’t believe in Jesus.

For a more in-depth analysis of the issue, if you actually ARE reading (I don’t know how it’s possible to read that article and conclude it misses the point of the main point it makes), you might try this one: https://artofericwayne.com/2016/05/02/why-people-hate-contemporaryconceptual-art/

LikeLike

conceptual art is a whole different ballgame!

I know it sounds crazy but still lifes can be conceptual!

but sadly truth is most such are broke like me!

But of necessary to existing we persevere!

Peter aka Arthur Really as in YES it really is art!

LikeLike

No, still lifes are not “conceptual” unless you mean that they too can have a conceptual aspect. They are not purely conceptual, nor subordinate to conceptual ideas unless they are purposefully atrocious. Ah, and I’m so sick of the A-hole comments from “anonymous” and “someone” types who are too cowardly to identify themselves.

LikeLike

Just an amazing article. Thank you so much for this analysis.

LikeLike

Thanks. So glad you found it useful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interest perspective on the topic, but I am having real difficulty as to if some of the key questions you are raising are purely rhetorical for the sake of your argument’s development, or your art educators had some significant holes in the theory curriculum.

So before getting to deep down the wrong side of that fork in the road where you ever required to read the following text books?

“The Necessity of Art: A Marxist Approach” Ernst Fischer ©1959 (Translator) Anna Bostock

“ZEN AND THE ART OF MOTORCYCLE MAINTENANCE: An Inquiry Into Values” Robert M Pirsig © 1974

or a more resent work after my years at art school that some course here in Australia now require.

“ART as performance” by David Davies © 2004

As I believe particularly the first & the last of those three books would clearly answer most of the question raised so far in this series about “Why People Hate Conceptual Art”.

All the best, W’Shawn Gray

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve certainly read Pirsig’s book. In any case if you understood those books you should be able to make a cogent argument based upon them on the fly. When people give me reading lists, which happens not infrequently, my feeling is that if they have read the books and can’t encapsulate the argument, that doesn’t bode well for the books, or instill trust in my that those recommending them truly understand what they are recommending. You must first indicate what the arguments are, and then, if I found that persuasive, I could seek sources that fleshed out those arguments. You may in fact be absolutely correct, as I did love the Pirsig book, but, as I said, I’ve been given reading lists before, and you will notice that I argue on my own two feet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am 43 and just beginning to delve into creating and appreciating art more seriously. My mother and father both made livings at different points in their working careers as artists, so I had early exposure and some casual interest in visual expression and creativity. Lately, I’ve begun spending the majority of my free time sculpting, sketching, painting, producing mixed media, conceptual installments (all at home just for my family), practicing lettering, etc. I am preparing to learn more about digital art. I don’t know much about any of it and in my quest to learn more about art I stumbled across your website. It has taught me more than anything else I’ve read so far. You cut right through the bullshit and open my mind. I now have a better appreciation for pieces of visual art that I would have probably poo poo’d before. I’ve also gained insight into how to improve my conceptual art. (Not to mention, I now understand the difference! Yeah, I’m very new to this world.) I love how you write with such clarity and balance about questions I have, such as the relative value of formal skill vs artistic skill/visual communication. I am broke and don’t normally donate money, but I found your content so valuable that I gave you $2. Sorry it’s not more. I hope you keep writing and making art. Your contribution is very valuable to me even though I’m not in a position to show it monetarily at the moment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Jessica. That’s great. I’m so glad my writing has been useful to you on your art journey. It sounds like you are really taking to art-making in an enthusiastic and very positive way. Maybe my own love or art echoes yours, and that’s the underlying thing you appreciate in my writing.

Thanks so much for the donation. Anything is great not just for the financial help (I can’t work right now due to a covid outbreak where I live), but because it shows genuine appreciation.

I’m mostly happy to hear I’m contributing to your rich exploration of art.

Best wishes in 2021,

Eric Wayne

LikeLike