It’s often the people who just don’t get it that are against conceptual art. The paint daubers, making their still life paintings in dusty studios, and those who, if it came right down to it, don’t really like art at all. That’s predictable because conceptual art is, as the name suggests, conceptually challenging. It requires a leap of understanding to “get”. Like other disciplines, such as Particle Physics or Psychology, one needs an education to appreciate the more sophisticated output in the field. We don’t expect the layperson to understand equations beyond geometry or algebra, so why expect them to understand highly complex art?

I happened to have the privilege of going to radical, conceptual art colleges. I graduated with honors from UCLA, and got a $10,000 fellowship which was awarded to just one artist per year. I got a 4.0 in “art theory”. Same in a “New Genre” class taught by mega-art-star, Paul McCarthy. So, I do have a bit of an advantage in understanding the genre I was trained in. And while the most highly paid living artists are conceptual artists who hire legions of art assistants to make multi-million-dollar art productions for them, they have made great sacrifices. In order to elevate art to the stature of philosophy, and as something that can change the way we think, and even alter the course of civilization, conceptual artists had to renounce what visual artists formerly loved most.

I think a lot of conceptual artists would have to admit that the reason they got into art was because as kids they loved drawing, album covers, book covers, and other imagery. Sci-fi and album covers were about my favorite, until I discovered the Surrealists and Abstract Expressionists. We loved art the same way budding musicians loved Rock (or music of choice). We wanted to make great images. We might have had a particular fondness for certain subjects (cyborgs!), colors (I loved crimson, but now it’s grass green), making compositions, working from our imaginations, and just making something that wouldn’t exist without our own existence. Often our art was personal. Aspiring musicians similarly loved melody, harmony, rhythm, chords, and lyrics… But as conceptual artists we needed to abandon all that, like a kid tossing his cherished childhood toys into the dumpster. We needed to challenge it, fight, and destroy it.

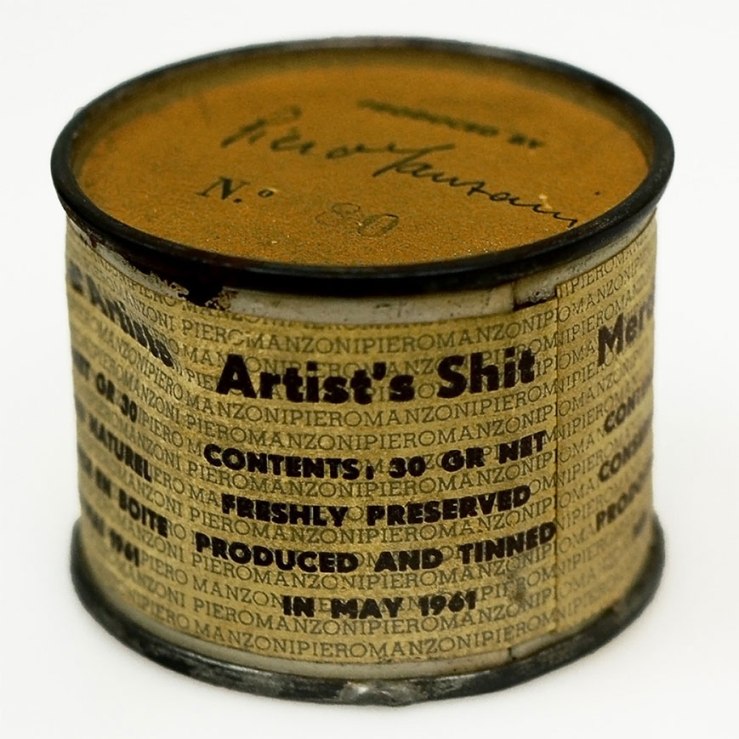

Our teachers taught us about artists like Marcel Duchamp (who exhibited a urinal as art) and Piero Manzoni (who canned his shit). And while at first we might have scoffed in dismissal, we later guffawed in recognition. When we “got” it. Many couldn’t make the cut, and like antelopes devoured by crocodiles when they couldn’t traverse the river with enough agility, fell through the cracks. That’s going to happen. It’s the survival of the fittest mind, and some just aren’t up to modernity. They fell back from the herd, while the conceptual artists were way out in front, leading the way.

But there was a price for even the winners. They’d traded in imagery, imagination, skill and craftsmanship for concepts. Conceptual musicians stopped picking up their instruments, and stopped making songs. Conceptual writers abandoned stories, plots, rhymes, and anything that resembled beautiful writing. And conceptual artists sidelined color, composition, form, and imagery. In all three disciplines it was forbidden to try to use one’s own skills and talent to craft something new from the imagination. We learned that it had all been said and done before, and now we should seek to find new ways of looking at what already is, or do anything other than what we originally wanted to do. We learned that anything goes in visual art, except visual art, which had now become antithetical to visual art.

When I was in graduate school I was lucky to study under teachers who were at the pinnacle of radical, conceptual, political art. They helped me to understand that as a white male, my best (and only) artistic option was to “deconstruct [my] white male privilege”. I had a unique advantage because of my blue eyes, and generally looking like I could have been a poster boy for the Hitler Youth. All the better to undermine myself via making conceptual art that educates other people about my privilege, which was the result of “institutionalized racism”. Without their help I might not have even realized how culpable I was, nor my duty to sacrifice myself for a greater cause: the empowerment of other, non-white-male artists.

However, we all knew that even if I did this artistic self-annihilation, it would be inherently inferior to other students’ work, whose purpose was to celebrate their identities and empower themselves. They were clamoring to the top of the mountain to take their rightful place, and I was stumbling down with a dunce cap and epithets pinned to my person. To help clarify this, one of my instructors in a graduate seminar looked at me, the only WMH in the class, and said, “We’ve heard from you for two thousand years, and nobody cares what you have to say anymore”. Such a clarion nugget of wisdom has stuck with me to this day. Naturally, and justifiably, my peers were pissed off at me for subsequently not joining in classroom dialogues. They saw it as my refusal to take responsibility for things like the institution of slavery, or to acknowledge how I had personally benefited from it. Why wouldn’t I admit that I was guilty of lynchings and reaping the profits of backs broken in the fields? I’d had my turn, goddamit, been nursed on a silver spoon, but I wouldn’t even admit it. Not even to myself.

This is why for me to pursue art was tantamount to continuing the suppression of marginalized persons and the underprivileged. If I spoke, someone else who hadn’t had a chance for two thousand years lost the opportunity. My peers would become righteously furious if I tried to point out that none of my ancestors lived in America during slave times, or that I had a working class background. I was still guilty. It was written in my DNA. I was the only WMH, and I was automatically THE NORM which they were rebelling against, and defining themselves against. I was the enemy.

While having a career as an artist was no longer an option for someone with my sort of DNA, I could at least not be a part of the problem, and bow out with dignity, humbly accepting menial work as my new and deserved fate. As my teachers and classmates rightly pointed out, as a white male I had nothing to say that wasn’t going to be a mere reaffirmation of an outmoded, racist, misogynist, colonialist, brutal, and domineering world view. My voice was inherently everything wrong with the world. Renouncing it would be the best thing I could do for art, while silencing it would be even better.

And while the more stridently political varieties of conceptual art, and their vendetta against the whitemaleheterosexualoppressor have sadly fallen from the forefront of contemporary art, privileged white male geniuses have stepped in to carry forth the torch of conceptualism. But even these newest members of an elite old guard have had to make deep sacrifices.

Perhaps the greatest sacrifice is the rejection of the ability to make a new image. For musicians this would mean fighting against the prospect of writing a new song. For writers it’s the abandonment of the quest for a new poem or novel.

So when people attack conceptual art for lacking any of the qualities people associated most with art in prior centuries, we need to remember the sacrifices they’ve made in order to make profound leaps of understanding, and to fight the prejudices of old fogy artists still addicted to their immature obsession with color, subject matter, composition, texture, meaning, and all that antiquated nonsense. A way to help understand conceptual art is to think that the more it looks like art, the less it is art.

Myself, I fell through the cracks. Admittedly, I no more truly understand why Duchamp is better than Picasso than I understand subatomic physics equations. Sure, I could write papers explaining it all utterly convincingly, but I don’t really “get” it. I am the antelope being devoured in the jaws of the crocodile. Despite my education, and unable to make the mental leap to be on the front line of cultural evolution, or even to fully appreciate my innate privilege, I’ve fallen back on childishly doing what I love: making new images with subject matter, color, compositions, and meanings that I find compelling.

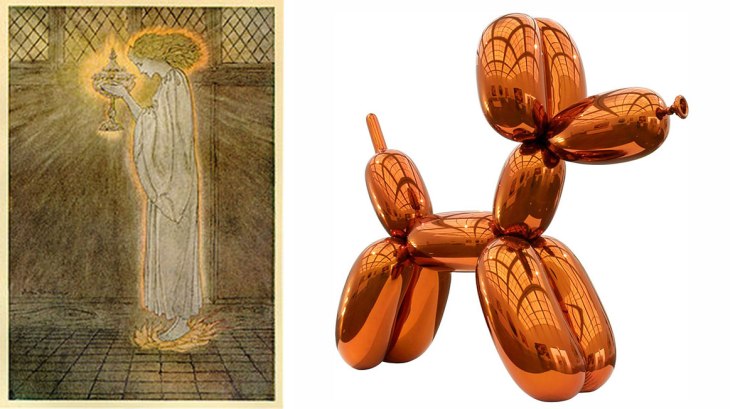

But this doesn’t mean that I don’t appreciate the great sacrifice even the most successful conceptual artists have made. Like monks seeking enlightenment who have renounced all sexual pleasure, and are forbidden to touch women, artists like Damien Hirst or Jeff Koons do not permit themselves to create their own work or use their imaginations. Damien Hirst didn’t have the pleasure of even touching the majority of his 1,400 dot paintings, and Koons isn’t allowed to try his own hand at molding his own sculpture (by his own admission, he’d ruin them). Instead, they look with eyes of infinite wisdom and charity at the world around them and choose among existing objects those which need to be brought to the attention of our species, and they hire skilled assistants to do the dirty work of making grandly over-sized copies of them. Like photo-realist painters, they must relinquish their own creative impulses, and pay heed to external reality as it is. And like a Zen Buddhist, to do so without desire or aversion.

They are the great seers of the age, if not the millennia. Their sacrifice of their own ability to use their own imaginations to create something new is akin to the fasting of Jesus or the Buddha under a tree, in order to break through to a greater vision and understanding. Before we had the Great Pyramid of Giza, the temples at Angkor Wat, the Colosseum, Stonehenge, The Great Wall of China …, and now we have the Balloon Dog: an unflinching incarnation of the NOW. It is the “shock of the new“, even if the author of the lauded book, and films of that title, Robert Hughes, didn’t himself care for Koons or Hirst (or Warhol, for that matter).

The conceptual artists have risen not only above art, but above being artists. They are our philosopher kings and saints. That they sell their art to the wealthiest of the wealthy – the cream of the 1% – for tens of millions of dollars, is their well-deserved reward. Unlike contemporary writers, filmmakers, and musicians, all of whom are fairly readily appreciated by lovers of culture (I’m currently salivating over the novel, “The God of Small Things” by Arundhati Roy, watching Werner Herzog documentaries, and listening spellbound to the music of Morton Subotnick), the conceptual artists are so far ahead that only the select few, and the wealthiest can approach understanding them. Those that can find psychological, emotional, or for lack of a better word, “spiritual” nourishment in contemporary music, film, and literature, but who merely get a chuckle or a shrug out of conceptual art, are not quite up to the challenge.

But perhaps there is still hope, and those of us who seem to have fallen immeasurably behind can free ourselves from the jaws of the crocodile, jump up and catch the lip of the crack we fell through, come to see the light of the new dawn, and recognize the Balloon Dog as luminous, iconic, and the holy grail of the new millennium.

Like children leaping at the string of a runaway helium balloon, we must keep reaching to understand conceptual art, for we are not the measure of it, but it of us.

~ Ends

Note: Apologies for revealing in the title that the piece is satire. Do people read past the first sentence or two anymore? Would they bother to engage the text long enough to realize it was laced with irony? And I also think I need a codicil, so that people don’t take me too literally. As satire I used some hyperbole, and a certain tone and language, for comic effect. It’s a bit of a satire on my own stance, imbuing it with extra rich and creamy sarcasm. I don’t mean for my position to be taken exactly literally. I like some conceptual art, like pieces by Chris Burden, but think there’s been too much emphasis on the conceptual art of the spectrum (all art has a conceptual element, but “conceptual art” is at the far end of it), as opposed to the more visual end. When I was in art school all emphasis was on conceptual art/political art, and the art I really wanted to do wasn’t even an option. I want art to look good, and be visually interesting. It’s like saying that I want music that sounds good, and is interesting. When one says that about music it’s so obvious that few would think it strange, but if one says it about contemporary art, it sounds reactionary. And the truth is that I think the Balloon Dog is actually OK, but just OK.

I think we made a mistake in overvaluing conceptual art, and believing that it was not just another form of art, but rather that it replaced image-making in a linear evolution of art. Conceptual art does not continue what Van Gogh or Francis Bacon were doing. It’s something different. As different as sculpture is from painting, painting from photography, and photography from agitprop… In the decade I went through art school, the emphasis was on conceptual art and political art, neither of which I had any real interest in before attending college. The kind of paintings I wanted to make were considered backwards. In reality they were NOT, but merely a different tradition. Conceptual art had not actually replaced image-making, as people thought at the time, just as they thought Postmodernism had annihilated objectivity.

Now we see artists like Peter Doig getting some recognition, after being ignored for a decade or more. People are realizing that images, like songs and novels are not going to die, because they are things that people have found enriched their lives for centuries. If anything needs to die it’s the shortsightedness and arrogance that believes that one kind of art-making can displace whole traditions. The sad result of this is the near worship of celebrity artists as changing culture forever, when they are only adding a bauble on an already rich tapestry. Disco didn’t kill heavy metal, and rock didn’t kill blues, jazz, or classical music

I’m a bigger fan of music than I am of “art”, because there is so much great music happening around the world. I love the Qawwali music of the Sufi religion that issues from Pakistan, as well as the traditional music of Tanzania (Hukwe Zawose in particular). I’m a huge fan of classic rock, 60’s psychedelic rock, progressive rock, and heavy metal. I’m also devoted to electronic music, including some very obscure composers. The idea that one kind of music would replace others, as opposed to just adding another choice, is ridiculous.

Nevertheless, because of conceptual art, it was conceptually accepted that visual art which was intended to be LOOKED at (as music is intended to be LISTENED to), was somehow irrelevant. This is like saying pizza is irrelevant, and only Sushi matters.

See my ridiculously awesome conceptual art parodies here.

See my new art here.

I think anyone who tries to tell another person that their voice isn’t relevant or worthy has big psychological problems of their own. Instead of helping each other or allowing each other to speak, I guess they find “pleasure” (?) in being “right” or making others feel inferior. At some point, we have to step back and look at the players and remove ourselves from dysfunctional situations. True, everyone has a right to their opinion, but I think there is a line/balance between sharing your thoughts and attacking others.

LikeLike

Yes. That was a critical flaw of the feminist/Postmodernist teaching method of the era. It had some strengths, mainly as regards promoting the art of people who hadn’t been given the audience they deserved. But when it came to the attack on WMHs or objectivity or Western culture in general, it was over the top, and sometimes self-righteously, and indignantly, judgmental and condemnatory. There was the definite idea that it was OK, or even ideal, to discriminate against certain people because of their presumed privilege.

LikeLiked by 1 person