Jeff Koons’ new paintings represent a radical departure from his prior work, though recurring motifs such as foil balloon animals and mild erotica give a false impression of sameness and continuity. However, unlike any of his previous works, in the new body of paintings Koons hasn’t merely appropriated already existing objects or images in their entirety for his highly skilled army of over 120 artist assistants to recreate in his factory studio – for the first time he got his own hands dirty creating the source imagery himself. This is a shift from anti-art to art-art. In this article I will examine Koons’ new method of working, the art historical lineage of the work, the distinctive characteristics of the pieces, and analyze my favorite of his paintings (I actually do really like one) in detail.

Method

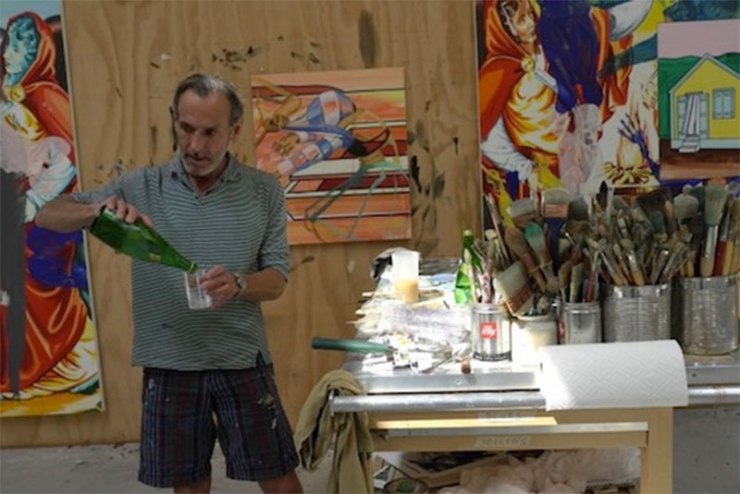

Koons first creates a collage on the computer, then has his crew of artists reproduce it on the large scale, using a meticulous grid and dot procedure something like paint-by-numbers. No matter how large the image, his assistants use tiny brushes, as Koons attested in an interview, “each of these broad sweeps is hand-painted with very small brushes, we never use sponges or anything larger.” No method is too tedious or time consuming for his inferiors.

The short video below of a visit to Koons’ studio includes an interview with an artist tragically painting a wall-sized Koons canvas, one tiny brush stroke at a time, basically acting as a mechanical part in an enormous printer. The original Koons is just a Photoshop collage.

It’s difficult to watch this film without thinking that Koons’ limitless budget is preventing him from rethinking his methods, because the kind of work his assistants perform is murderously tedious, boring, and ineffectual.

I have all the same reservations about a crew of artists making his paintings as I do about them making his sculptures, but in this case they are only copying instead of having to figure out how to do things like make a three dimensional sculpture from a photograph of a couple with a litter of puppies.

What they are copying won’t get Koons sued for at least a fifth time for copyright infringement, because the collage is completely his own creation. He had to choose and arrange the images himself, work out a satisfactory composition, balance colors, and achieve the desired overall effect. His workers are painstakingly making exact replicas of Koons’ Photoshop collages, essentially doing something advanced printers in the future will probably be able to closely replicate in minutes. The essential art and vision is the collage itself.

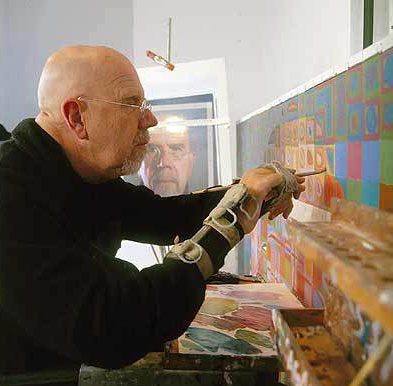

Contrast Koons’ methodology with that of Chuck Close, who could hire assistants to paint his large canvases, but instead exactingly completes them himself, even after enduring a collapsed spinal artery that left him nearly paralyzed in 1988. After his injury, the artist insisted on doing his own work with a brush strapped onto his wrist. For Close, the execution of the art is more significant than the idea behind it, and hence has to be performed by the artist himself.

Typically it is precisely the fastidious perfection of Koons’ pieces that impresses. It is not the idea of a white Michael Jackson with an identically dressed white monkey sculpted on a massive scale in ivory that wins us over, it is the realization of the idea. What is still startling about any of Koons’ balloon dogs is the flawless craftsmanship. It wouldn’t matter if the subject were marshmallow Easter bunnies, or pieces of bread slathered with peanut butter. If you make a faithful representation of anything large enough, and out of expensive materials, the result will impress.

Usually when you take away the consummate craftsmanship, sumptuous materials, and evidence of hundreds or thousands of hours of work, there’s nothing left to a Koons’ piece except a rather insipid idea that any group of young artists could have scrawled upon a napkin while stoned after attending an “Intro to Postmodernism” class.

Postmodern philosophy and the art spawned from it hold that any distinction between high and low art is purely arbitrary and subjective, thus commercial art and kitsch are just as relevant and interesting as, say, a Jackson Pollock or Van Gogh canvas. Many contemporary artists therefor think it’s radical to serve up unadulterated kitsch as fine art, and call it a day. Rather than just take the actual object, say, a balloon dog, and exhibit it in the museum as Duchamp infamously exhibited a urinal, the contemporary postmodern artist goes through all the trouble of making a replica in some other material (and better if he can hire someone else to do that menial labor). Once one sees through this, it’s not so much radical and groundbreaking as it is a simple-minded gimmick.

The initial collages Koons makes for his paintings, on the other hand, require skill, and fall within the classical arena of aesthetics. They can be accessed and assessed on aesthetic grounds. They are attempts at art as we know it. This has perhaps been swept under the rug because his big selling art has all stemmed from the idea of exhibiting kitsch (and other cultural garbage) as the highest achievement of culture. The new painting is a different religion, and the art market might not like that if they caught on.

Art Historical Lineage

As with so many of today’s artists, Koons’s philosophical mentor is Andy Warhol, who boldly stated, “Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art,” but for the style of his paintings Koons is fully indebted to James Rosenquist and David Salle.

Rosenquist was trained as an artist but then made a living for several years as a billboard painter.

Later he decided to take those skills, incorporate them with his art training, and make enormous paintings for the indoors instead of outdoors, and better yet within galleries and museums. Rosenquist borrowed popular imagery, layered it, combined it, and interlaced it with his own brand of more abstract design elements.

Much of what you will see in Koons’ paintings of over 40 years later can be found in the above image by Rosenquist, including images of junk food, unconnected body parts, everyday objects, and iconic American imagery.

Rosenquist’s “I Love You with My Ford” not only is the father of the painterly art of Koons and Salle, it looks nearly identical to early Salle paintings. The canvas is divided into three parts, but the biggest section and color are awarded to a heap of canned spaghetti noodles. This kind of ranking of the mundane as equally or more real and substantive than the romantic or people-centric serves to destabilize conventional narrative, and is the main thrust of his early work (later he becomes more decorative), and that of his followers, Salle and Koons.

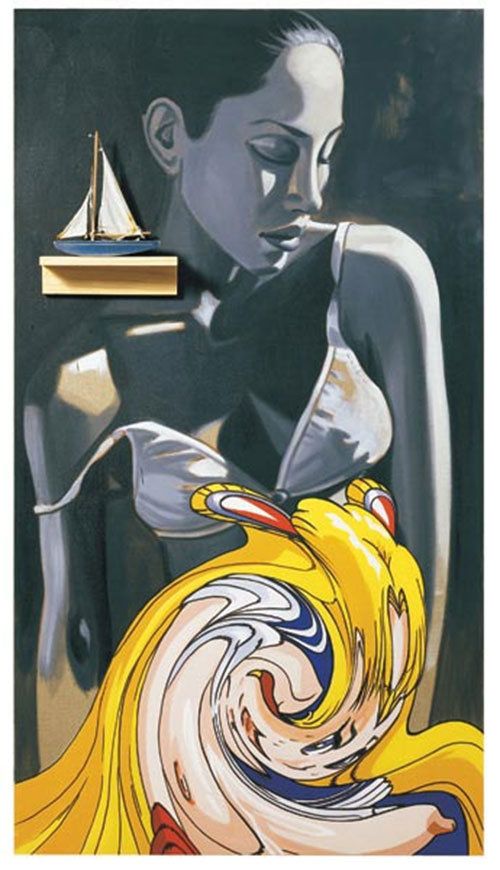

The above Salle painting is structurally similar to Rosenquist’s I Love You with My Ford. At the bottom is a swirling mass of yellows and oranges, though it looks like a pornographic cartoon with a swirl filter applied to it. In the middle section is a loosely painted, gray-scale figure that is entirely in the manner of Rosenquist’s billboard-painter, nonchalant handling of figures. The ambivalent sensuality that is and isn’t – the form being enticing and the color clinical – is precisely the same as the upturned mouth in Rosenquist’s painting. In the top third of the painting, on equal billing with the subject’s head, is a toy sailboat – another stationary vehicle, symbol of industrialization and a product of mass production. Salle takes off where Rosenquist once left off, and both branch in different directions from there. For my tastes Salle took the more interesting path, exploring odd juxtapositions, and including physical objects, outlines of figures, flat decorative textures, and anomalous painterly swatches.

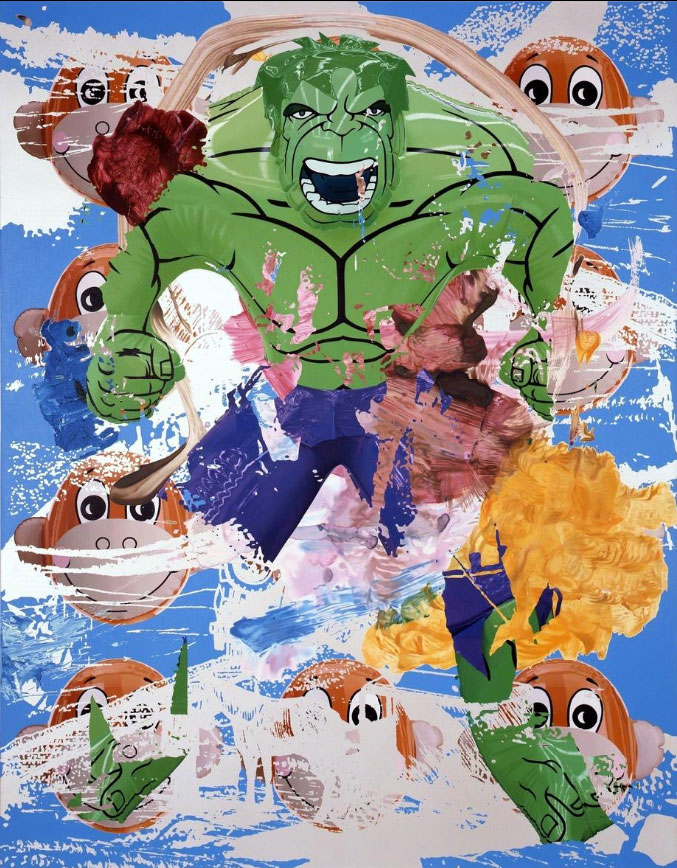

Everything Koons does in his paintings had already been done by David Salle in the 80’s, including using cartoon characters. Notice the use of scraps of patterns, articles of clothing, generic drinking vessels, splotches of color, and fragments of clothing. In the following image pay attention to the scrubby brushwork on the pink, upside-down head in the center of the left panel, as well as the outlines of nudes. This is a look Koons will try to repeat in his own collages.

Unlike Koons, however, Rosinquist and Salle painted their own canvases. In the case of Salle, the brushwork is often undemanding, and even if he could hire a squadron of artists to render it for him, he might as well do it himself, and he probably needs to in order to get the specific aesthetic he is after. Both these artists are sophisticated aestheticians, and their work is the rarefied achievement of the inspired individual. They may appropriate imagery from popular culture to incorporate in their own complex compositions, but they would never copy something wholesale, change its material or setting but not its inherent aesthetic, and brand it as their own, as has Koons, at least until he started making collages. Someone like Salle, who is a poster boy for Postmodern collage, may bristle at the notion that he is trying to make unique paintings from an inspired position, as that was one of the cornerstones of now-outmoded Modernism, but the selection and juxtaposition of seemingly mundane objects into a meaningless whole which therefore achieves a new, uncategorazable but profound meaning, requires a highly refined taste in the mundane, and the combinations thereof.

Characteristics of Koons’ Paintings

Originality is not Koons’ secret weapon (it’s money), so there’s precious little to add to terrain I’ve presented as already established by the likes of Rosinquist and Salle. However, as an offshoot of the work of Salle and Rosenquist, Koons’ paintings represent his fledgling attempt at making original art. The following is a breakdown of the key features of Koons’ paintings, with visual examples so that they can be more easily understood. To coincide with the surface superficiality of Koons’ work, and its supposed transcendence through acceptance of the commonplace, I’ll make it a Top 10 list.

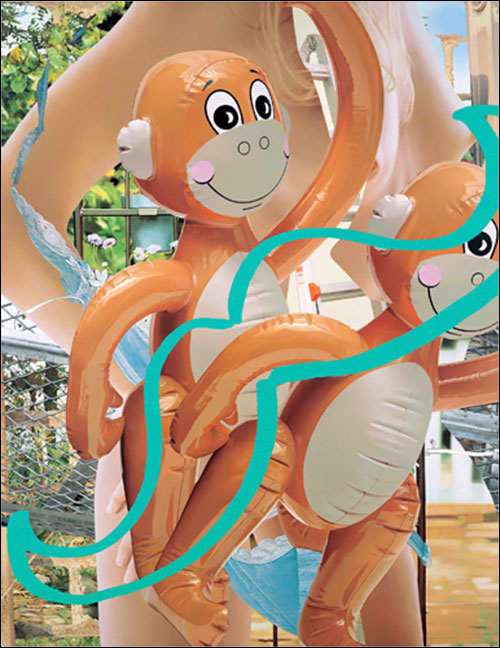

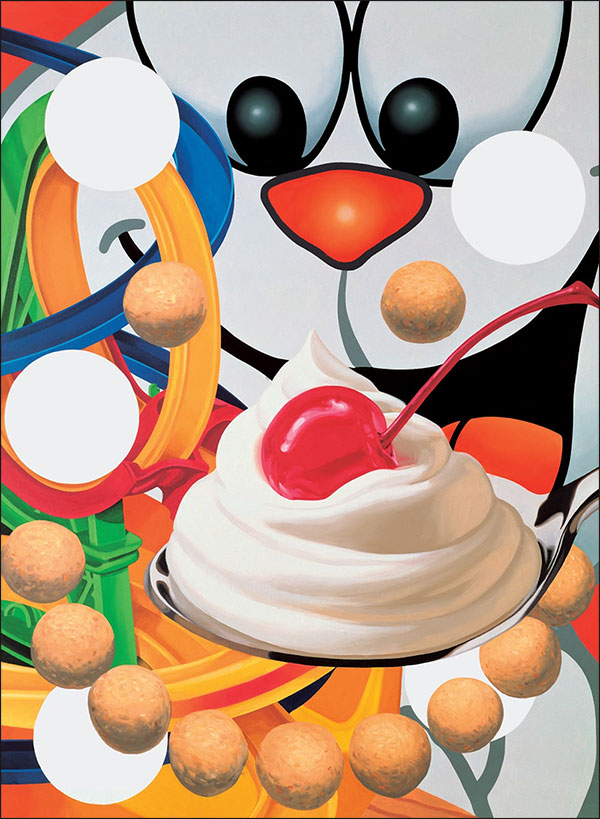

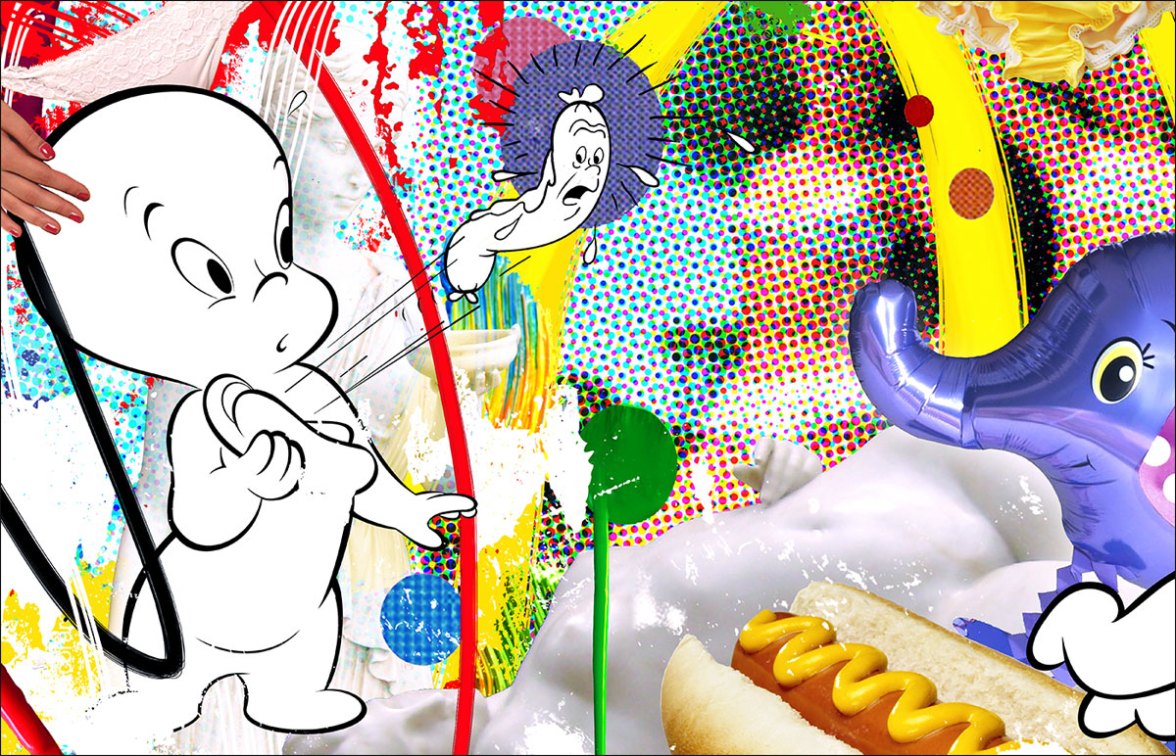

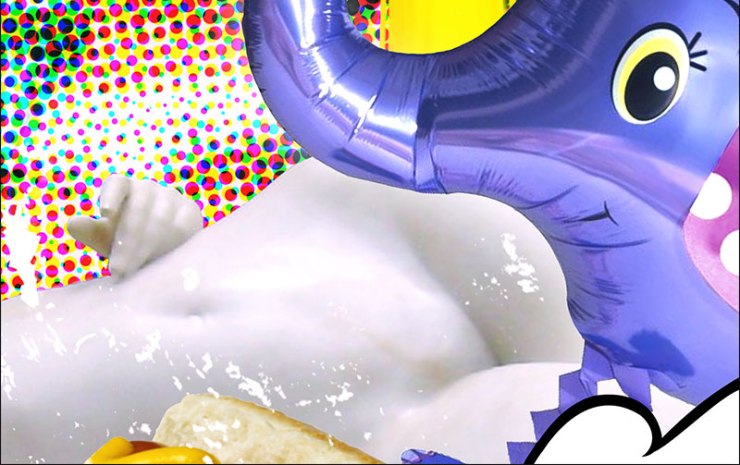

1) Inflatables. A borrowed trademark from his sculptures, inflatables (animals, toys, balloons) are like a fingerprint in Koons’ paintings. In the better works, they add a peculiar shininess and high-reflectivity rarely seen in painting.

2) Food. Perishable food is immortal art. What have we got here, bologna, ice-cream, and milk in the background…?

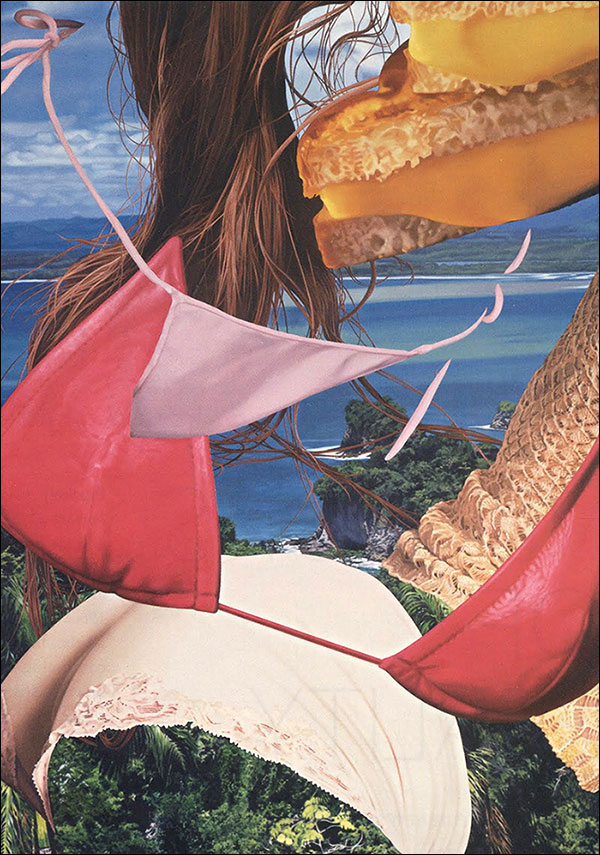

3) Cut-outs. Particularly in his earlier “paintings”, which are more accurately “collages”, the cut-outs seem somehow harsh, as if they were clipped out of magazines with scissors. They also smack of fundamental Photoshop “remove background” tutorials. Cut outs include body parts, hair or wigs, food, and clothing. I like to think that Koons bothered to select and isolate the source images himself in Photoshop, but that is unlikely. He probably uses pre-cut images, or has assistants do the grunge work for him.

4) Sexy girls, pin-ups. It’s a slick, cliched, airbrushed, and superficial sex – like a magazine ad – that has little if any real allure.

5) Neoclassical or Baroque sculptures. The inclusion of these are doubtlessly to lend Koons’ art a certain gravity but more importantly to link him, by association, with the old masters. This may sound like an exaggeration, but in an interview with art critic Robert Hughes, featured in his “New Shock of the New”, Koons’ suggested his sculptural works made him an artistic descendant of Michelangelo. The example below shows several of the distinguishing features of a Koons’ collage painting.

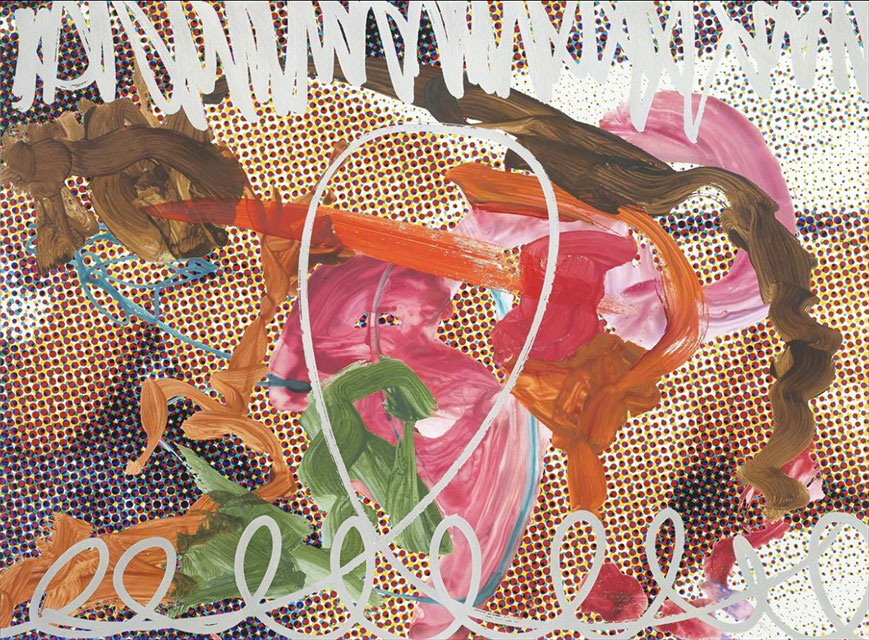

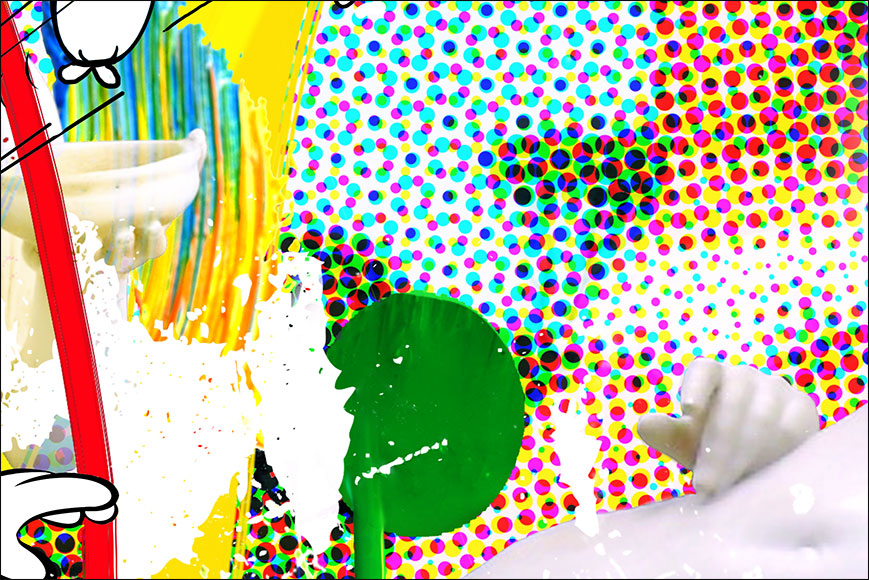

6) Line drawing on the surface. This technique borrowed from Sallie appears in most of Koons’ paintings. It serves to suggest multiple planes, surfaces, and perspectives simultaneously. This can easily be seen in the above painting, with the horrible sketch of what looks like a sailboat or a vagina. Below is a more abstract use of surface lines, which often are the simplest of scribbles. If you are thinking along the old lines of, “my 3 year old could do that,” this time it’s OK, because Koons’ incorporates his children’s scrawls into his art.

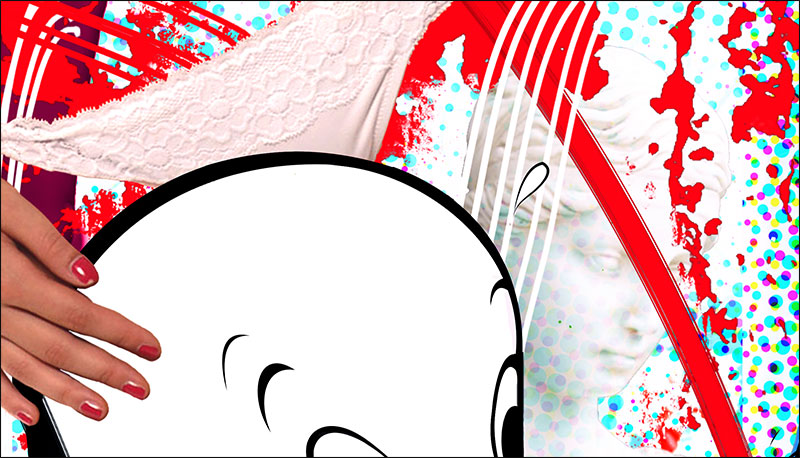

7) Empty underwear. You find this in a lot of Koons’ paintings. There are underwear but the girl wearing them has been cut out, so the form is retained minus the person. This trick implies space and form – that of the missing body – without rendering it in any way.

8) Picture plane flatteners. Geometric, usually round shapes that function to remind us that we aren’t looking into an illusionistic window, but at a flat surface.

9) Faux painterly strokes and swatches. They are “faux” in that they have their origins in the vigorous brushwork of the Abstract Expressionists, such as de Kooning, and as such are a record of the action of the artist’s motion, but are themselves just digital stamps. In the case of Koons the painterly smudges and splashes are used for effect, something like the Abstract Expressionist’s, but also closely referencing Salle, and are painted on with little brushes, so that a stroke that looks like it took seconds will have taken hours or days to meticulously copy. I suspect the reason he started incorporating brushwork was to get a more spontaneous look, and to appear less like the type of collage anyone could make with scissors and a magazine. Koons probably used a Photoshop brush (in this case a kind of stamp) to create his strokes, because the same strokes are repeated, but reversed… I have some similar PS brushes.

10) Magnified half-tone backgrounds. Half-tone is the overlapping dots used to create blending of colors in images, such as in magazines. This might be his way of linking himself to Georges Seurat and Pointilism, or he could just think it’s a cool effect. As with Pointillism, you get the surface pattern and illusionistic depth simultaneously.

11) This one goes up to eleven = content. It took me a while to fully get this, which is a kind of NOT getting it. There is no content. There is no irony. Jeff Koons likes kitsch. Many of us, myself included, go digging for meaning and substance in art. That’s a mistake with Koons. His work is meant to be visually seductive, and pretty, and that’s all. They really are just bright shiny objects. There’s no message in the use of imagery from popular culture, no hidden meanings, and no critiques. This is deliberate, and a completely literal attempt to make art based on Postmodern theories, according to which, there is no true reality, objectivity, or meaning. So, when Koons says his work has no meaning, it’s because he believes it shouldn’t, and that’s what makes it good. This kind of hardline Postmodernism has been discredited as overstating the case to the point of stupification and vapidity, partly for the irony of trying to appear more profound by denying profundity exists. Koons reflects the era we live in, but doesn’t intentionally comment on it. I would have understood his art better, and sooner, if I’d had a lobotomy before looking at it. Trying to find meaning in Koons’ work is like trying to find vitamins in a diet soft drink. Jeff speaks of his art as happy, generous, filled with love, non-judgmental, and accepting: blase generalizations that sound like a New Age self help slogan, and have little or nothing to do with anything in his actual art. He likes baubles, flowers, hearts, and other stuff that I never liked, even as a kid (I went in for movie monsters, toy helicopters, lizards, spiders, aliens…), and he rightly guessed that a lot of people would like them better than more challenging art.

Let’s take a closer look at one of his better paintings

This is a new painting, and it appears that after messing about with collage for over five years, Koons has finally become adept enough at something to attempt an aesthetically pleasing and complex piece of art (though the underlings still had to paint it in a way that hearkens back to the proverbial scrubbing the floor with a toothbrush).

What stopped me in my tracks upon encountering this image was the zig-zag mustard on the hot dog. Here we have food again, but this time it’s got attitude and isn’t just there to remind us how silly it is to have food in a painting and isn’t that wonderful to accept. The compositional energy is like a coiled spring. There’s even a pair of Casper’s legs springing off the far right bottom of the canvas.

Casper himself seems luminous because of the crisp lines, and the sleek black against the fields of white. There’s another hot dog leaping out of the bun because it’s terrified of him. Wait a second, there’s a connection between two of the images in the same painting? What’s this? Once my eye found the terrified frankfurter, I noticed a new device, which is a sort of round patch Koons is using as a picture plane flattener. They have their own textures as well, and the eye is invited to compare the weave of the various dots and ovals, which remind me just a bit of the dots on Wonder Bread wrappers.

There is of course the trademark inflatable foil animal balloon, and in this case it’s gorgeously colored and highly reflective. Even the zig-zag of it’s accordion legs parallel that of the mustard, though technically doing so perpendicularly. But most striking and elegant is how the reflection on the elephant matches the curve of the hip of the supine Baroque statue. It gives the impression we are looking at and through the balloon animal, and highlights the sensuosity of the sculpture. This may be Koons’ most erotic use of a Neoclassical sculpture in his paintings. I noticed the finger of the hand of the sculpture happens to cover the groin of one of the twin girls in the bikinis in the background, suggesting a likely unwelcome surprise. This playful spoof on gender is a refreshing development from Koons’ usual deadpan regurgitation of magazine cut-out ladies that makes one wonder if he’s ever heard of feminism. The second classical sculpture in the background is holding a chalice under the frightened hot dog.

The more I looked at the image the more I discovered. There’s one of those empty pairs of underwear in the upper left, implying a body, except she has a material hand and it’s on Casper’s head. Her hand gains additional significance because it appears to be the object on the top layer of the canvas. There is another pair of yellow underwear on the top right, but uninhabited, and look as though they’d been slung over the canvas. And is it just me or do the large yellow loopy brush strokes evoke the golden arches? There is a lot of reminiscent Americana here, from a remembered adolescent vantage.

The characteristic Koons half-tone background is there (but this time it glows a bit like Lite-Brite), as are the girls, the anomalous brushwork, and the drawn lines on top, though here they seem much bigger than the canvas, so that we only see the slightly-arched angles of them. The green dripping blob in the middle is a new device, not only giving the illusion of bas relief, but also of freshness. It looks as though it could have been applied seconds ago.

I’m not even sure that meaning or interpretations are entirely inappropriate with this work. However, the title, “Arousing Curiosity” leads me to think Casper is a symbol of a boy’s first libidinous feelings, and probably a corresponding bodily reaction. This could be a response to the naked sculpture or girls and their underwear. Once one catches onto the obvious the drips and elephants trunk… start to seem like deliberate and playfully humorous choices. I would hesitate to get bogged down into such a reading, however, as I think the narrative, to the degree there is one, is just a backdrop to evoke awakening, newness, and discovery itself.

This painting in particular signals a shift in Koons’ artistic awareness and sensibility. While his other collage-paintings all subscribed entirely to a now-debunked, overinflated strain of Postmodernist conviction that all narrative is spurious and all meaning meaningless, with his latest work, Koons is attempting to suggest a story, an interpretation, a meaning, an identity, and a humanity. Koons has made the leap from Postmodern anti-humanist art, to a Post-Postmodern reintroduction of the human, reality, and what matters into art, while still understanding and incorporating kitsch, popular culture, odd juxtapositions, and other understanding gleaned from Postmodernism. “No”, now says Koons, “reality isn’t purely a fiction and superficial. I can REMEMBER when the world was fresh for me and rife with meaning, when girls were mysterious, and I was subsumed by physical attraction, and, to hell with it all, I miss reality”.

I read that this painting was damaged or had some small imperfection, so is back in the studio being reworked. I hope to see this one in person, and that we will see more work in this direction. His imagination, eye, and intelligence are apparent here as I’ve seldom seen in his other work. I almost want to take back all my comments about lawn furniture, bird baths, and shiny baubles tailor made for the 1 percent.

It’s amazing how much work your pour into your posts and pictures. I’m grateful for the education in Art History (particularly Contemporary Art). Unfortunately, the Koons(es) of the world will continue to topple artists who actually do their own art, because they have the $$$ and the brand name behind them. Koons is truly the flagship leader of today’s art world, a perfect representative of art by the 1% for the 1%.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s what I been sayin’ all along.

LikeLike

You sound like a newbie to art.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sometimes the less you know the more you think you know.

LikeLike

BRILLIANT: “Originality is not Koons’ secret weapon (it’s money). “LOVE this article. koons is the used car salesman/stockbroker i most love to hate in all the world. let’s not forget tho that Andy had meaning and method to his madness, he was the first, he innovated, and despite his many comments to the contrary which were part of his brand and his overall conceptual art lifestyle, he actually was commenting on america and the modern era with his work, unlike koons, who not only is deriviative of so many who came before him but meaningless trash who is merely celebrating the worst takes on popular culture.

had meaning and method to his madness, he was the first, he innovated, and despite his many comments to the contrary which were part of his brand and his overall conceptual art lifestyle, he actually was commenting on america and the modern era with his work, unlike koons, who not only is deriviative of so many who came before him but meaningless trash who is merely celebrating the worst takes on popular culture.

LikeLike

Glad you liked it. I’ll try to keep an opn mind about Warhol, but I’m on the complete opposite end of the spectrum when it comes to my tastes in art, at least as regards my favorites (art is a bit like music and it’s always good to mix things up here and there to keep it fresh).

LikeLike

I know this isn’t the newest article, but as someone who’s been studying Koons for a little bit of time now, I have to disagree with one of the key assertions you’ve made here. That being that there is no content in this work. Now, a lot of this is from my own head, but I’ll try and back up my thoughts as best as possible. Yes, the simple moving of kitsch to fine art, or low culture to high culture (or in Koons’ case, sometimes the reverse), is the basis for the work’s acceptance. However, I believe that there is far more specificity in these pieces than even Koons himself would readily admit.

The first tier of potential content lies in an idea that Koons explicitly lays out in his “Conversations With Norman Rosenthal” book, as well as several other interviews. Koons believes in a world where art is truly for everyone, not just the white collar, educated, tastemakers who can afford his work. He claims that we are each “perfect” and our personal histories are “perfect.” He does not wish to create work where an understanding of art history is necessary to appreciate the art. For example, his shiny and monumental Celebration sculptures likely will captivate an 8 year old boy in much the same way as the 67 year old art critic. The work beckons you to come as you are. He constantly is speaking about “acceptance” and I believe that if you cut through the immense amount of fluff surrounding most of his lucid and startlingly profound statements regarding his own work, that you begin to see a constant thread emerging. Koons is essentially welcoming the entire world with open arms, total acceptance, to view his work from a level vantage point and in doing so, thrusts this idea of self acceptance upon the viewer. It’s a sort-of touching sentiment, but the ultimate effect is more heavy and philosophical than it is heartwarming. The content is you. Koons may even be attempting to lead the viewer to this very conclusion with his recent use of mirrored surfaces in his sculptures (although mirrors have been used in his work since at least 1979). Now, this may be a beautiful revelation, as it was for me, or a cheap, gimmicky “mind-fuck” that serves as further evidence of his career as a talentless hack, depending on your perception and previous opinions about the artist. But the claim that there is nothing there beyond the elevation of the kitsch to the realm of fine art really doesn’t make sense from either standpoint.

Sorry that this has turned into an essay, but I have one more potential area in which content could be found. And this one comes more from speculation and psychoanalysis than from his own statements. Koons’ work in college, before the Pre-New and the New, was deeply introspective and emotional. More of a cryptic and beautiful diary in contrast to the more outward commentary that would dominate his work in the coming decades. I believe that it is possible the work has come 360 degrees and the painted collages and sculptures are actually a deeply personal expression of his own narrative. In interviews, there is a vague sense of insecurity which Koons attempts to hide using a carefully crafted language he can call upon when asked to explain a work. He has built a fortress to protect himself and his work out of vague statements instilling his art with a sense of universality that he recites almost word for word each time he is questioned. But what if this is really just a facade meant to distract us from the shockingly personal subject matter of his work, specifically beginning in the early 2000’s. By the time his divorce and custody battle ensued, he was already in the spotlight and even he could not deny that there was a quantifiable effect the experience had on his work. Take the paintings from Easy Fun Ethereal. Koons has even stated that he hopes one day when his son sees this work, he knows he (Koons) was thinking of him. The empty underwear could be the absence of his ex-wife. If one looks, they can find all sorts of symbolism alluding to Jeff Koons’ own insecurities about his role as a father, the childhood of his estranged son, and perhaps even the complex relationship between the ephemeral nature of life and the permanence of a mistake.

Then again, I could be looking way too deep. Anyways, I would love your thoughts as I really enjoyed your article. Sorry this ended up being four times as long as I had planned.

LikeLike

Thanks for that comment, Danny. It’s great to have intelligent, well-crafted challenges to my arguments, even if it’s more than a year since I wrote an article. Other comments I have to delete because of the names people call me. Incidentally, did you realize the painting “Arousing Curiosity” is by me, and a parody?

I am familiar with the arguments you pressented, as I’ve watched Koons defend his own work, punctuating his attempts to articulate anything credible-sounding with endless “uhs”. But I don’t find the arguments at all convincing, and they seem more like after-the-fact alibis. Yes, he did say about his giant kitty, in an interview with Robert Hughes, that a child could like it. And in another interview he talked about how his hearts, made of tons of polished steel, reflected the viewer.

Not only do I find those arguments unconvincing, and uninteresting, they don’t even make sense to me. Everyone is perfect?! What does that mean? Sounds like new age bullshit on a platter. He’s also said, “God is on my side”. Check out one of my other articles on Koons, in which I discuss his self-proclaimed purposes here: https://artofericwayne.com/2014/08/23/is-the-influence-of-the-ultra-rich-killing-art-part-3-jeff-koons/

And in another article I discuss why his stated purpose is probably subterfuge, because the real objectives would probably insult the mass of people: https://artofericwayne.com/2015/01/04/koons-appropriation-and-plagiarism-again/

Koons himself has stated that his work has no meaning, and this is similar to Stella’s argument that a painting is just an object. And I do think the meaning really does have to do with appropriating Kitsch, and one must have some understanding of art history, especially of appropriation, starting with Duchamp’s infamous “Fountain” in order to get it. For Koons to say his work flatters the viewer who takes it at face value is as convincing as if Duchamp were to say that his urinal was a goregous physical object (he says he deliberately chose extremely innocuous objects which were neither atrractive nor repelled, and hence refuted aesthetics, in which case seeing his urinal as pleasing is precisely to miss the point).

Koons’ work is, or WAS about appropriating kitsch, recontextualizing it, and presenting it as art with a wry remove. It has an element of humor in it, which is the best thing about his art. Later, when because of his celebrity he was embraced by everyone who embraced celebrity unconditionally, it was no longer desirable to be the cool appropriationist making junk culture into monumental works of art. This is when he performed his self-lobotomy of the intellect, and fell in love with his own transmogrification of kitsch. He had to have grown soft on the tens of millions, fawning critics, attention from pop celebrities, and fame unimaginable to virtually all living artists. Softness became his message. Now he loves everyone as perfect, because he has it all and life is just too easy.

Oh, wait, did he have a divorce? Who didn’t? My parents were divorced. I don’t even have enough money to get married. I can’t afford to have children or a family. His travails are the hardships of royal families: the faux-tragedies of the extraordinarily privileged when everything isn’t absolutely perfect. Two of Francis Bacon’s lovers commuted suicide, one on the night of one of his openings. Real people lose their families in drone strikes. Koons is ultra privileged, and his woes are so overshadowed by his wealth, insider status, and fame that they don’t amount to anything.

If his work is personal, it doesn’t show at all, whether or not he is trying to hide the fact of it. The idea that he is everyone’s artist is just a smokescreen for the reality that most everyone is alienated by his work. Postmodern appropriation has gotten extremely old, and I’d say it’s defunct as fine art or challenging in a world where because of technology everyone appropriates anyway (any time you share something on Facebook you are recontextualizing it, hence appropriating it). Stunning us with appropriation is about as likely to work in the new millennium as is shocking us by magically producing a flame from a lighter.

One can’t take the appropriationist out of his work, and his defense does not attempt to explain why he appropriates rather than make new things for everyone, and affirming everyone’s perfection. And if his work is personal, let it show. Lastly, in today’s world, where most artists will be squelched for purely economic reasons, art that requires millions to produce is a social abomination. I’m sick of multi-million dollar productions as the highest form of art. They are gargantuan spectacles hiding the lack of intrinsic content.

Anyway, that’s my opinion. Thanks again for sharing your take. Hope we can disagree but still be friendly and open-minded to each others views.

LikeLike

Haha I thought so, but I wasn’t sure. that’s great.

I can definitely appreciate your views, as a part of me still agrees with you on some level. I don’t think we’ll likely ever see eye to eye on Koons, so let me just ask you this, purely out of curiosity: is there value in making art with an egalitarian spirit? Is that even possible? Is there someone that’s doing it (art) “right” presently to you? And if the work Koons does IS meaningless or played out, what isn’t? Does there have to be tragedy or narrative or explicit timeliness for a work to be considered significant?

I guess these questions really come down to your definition of art, which is such a fluid and dynamic concept, it’s amazing anyone agrees about anything.

Anyways, thank you for the reply. Always a pleasure to debate art with a person who’s both truly knowledgable and seemingly very passionate at the same time.

LikeLike

I know this is an old post but I tend to read what interests me. It’s been clear for some time that kitsch is fashionable and as Constable said way back, “Fashion will always have its day.” There is a painter who does imitations of this sort of thing fifty miles down the road from me, though his work is more derivative of Salle than Koons. He clearly puts together a collage of photos on Photoshop, projects it and colors it in-paint by numbers indeed! But since he can’t afford assistants his work isn’t even painted that well, but still people love it. They see MEANING in it. I see it as insipid socio-political posturing not painted very well; but hey, that’s me. While I’m on the topic, Mr. Epstein is seeing way too much in Koon’s work. He should see only $$$$.

What baffles me is how people still categorize good and bad art. It usually comes down to what they consider new or avant-garde. For example: the debate over abstraction vs. representational painting. It’s a bogus argument from either side. Though a cliche, all good painting is abstract. Delacroix wrote in his journal in 1850 that he could see a day when painting would not need a subject matter. All good painters understand this, i.e. that painting is an abstract language. And let’s face it, there is nothing cutting edge about abstract art anymore. And there is nothing avant-garde about doing pastiches of Warhol, et al, which many still do. Not, at least, if that is one’s only criteria. It’s 2018 for Christ’s sake, not 1960.

I’ve glanced at a few of your other posts and like what I’ve read so far, which worries me. Maybe because it’s not the touchy-feely bull-shit one usually reads on these blogs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey man. There’s kind of another level of a lot of my art criticism. Shhhhh. “Arousing Curiosity” is a parody by me.

LikeLike

I enjoyed your article. Very insightful work pointing out the crap that is being produced and lapped up by those who will never run out of funds.

But brother, I’m afraid your giving koons way too much credit by ‘finding’ meaning in even the one work. After all as quoted he even states there is no meaning in his work. Perhaps we should do him a favor and not give him any.

Maybe this way the market for him will finally collapse and ‘his’ slaves may be set free.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, but the one work I praise is a parody by me. That’s the real criticism.

LikeLike